An Exhibition from the Gerald Cantor Foundation

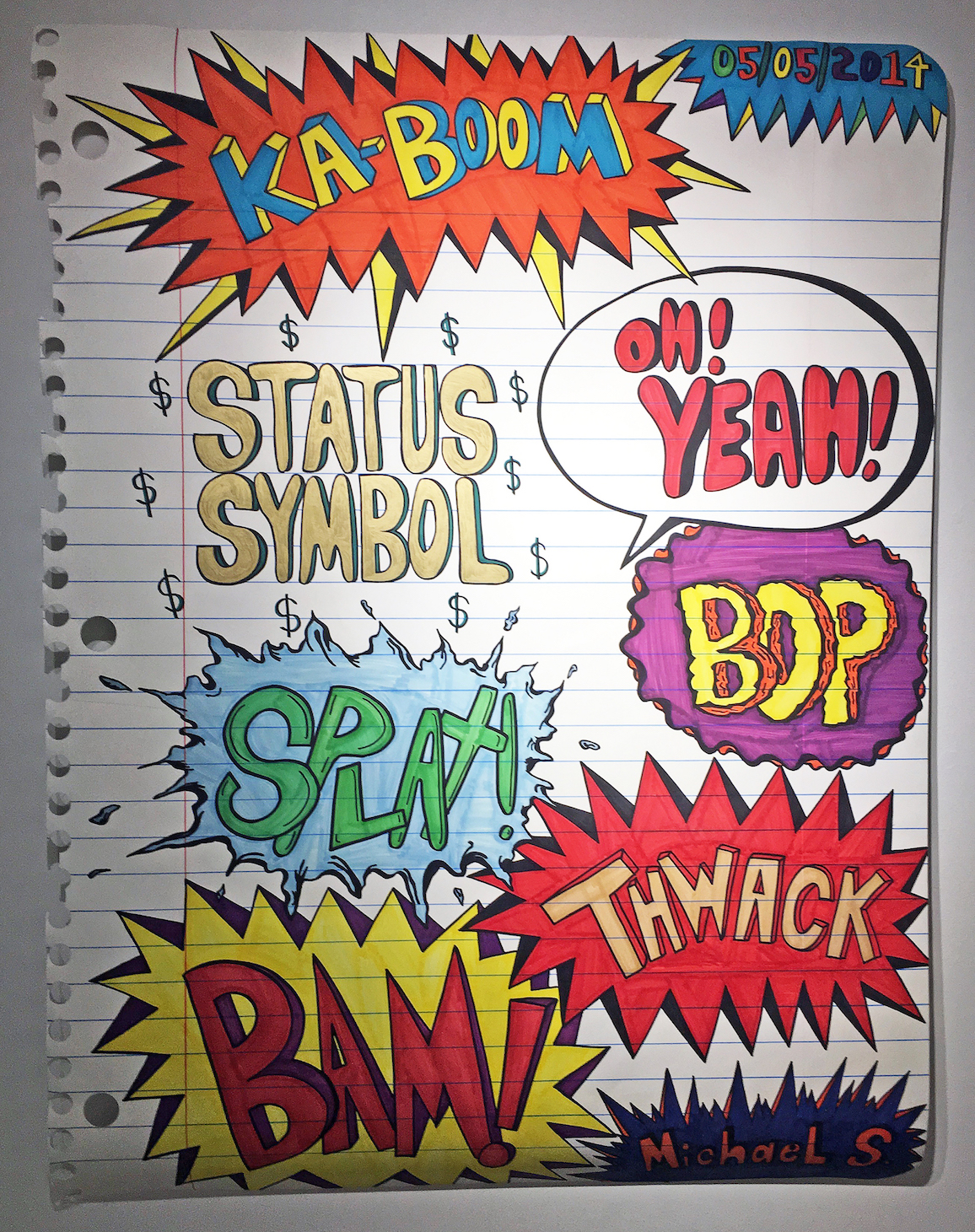

Installation Image Flint Institute of Art

Fresh out of the army, in 1946 Gerald Cantor purchased a bronze version of Rodin’s The Hand of God, thus beginning what he called his lifelong “magnificent obsession” with Rodin. Today, with over 750 sculptures and drawings in its collection, the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Foundation boasts of the world’s largest private collection of works by the artist, the majority of which have been gifted or loaned to museums throughout the world. Rodin, The Human Experience, on view at the Flint Institute of Arts, is a muscular exhibition of 45 sculptures on loan from the Cantor Foundation, offering an impressive survey Rodin’s artistic career. Expect to see more Rodin in one place than nearly anywhere else this side of the Atlantic.

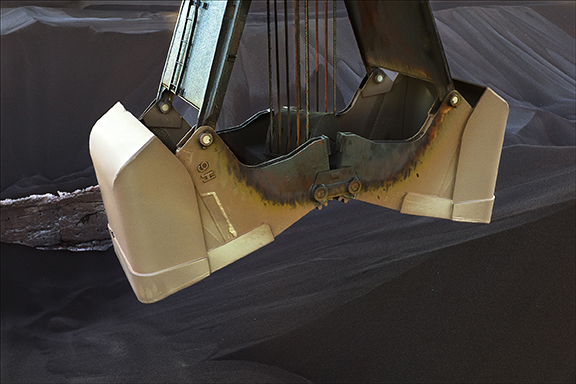

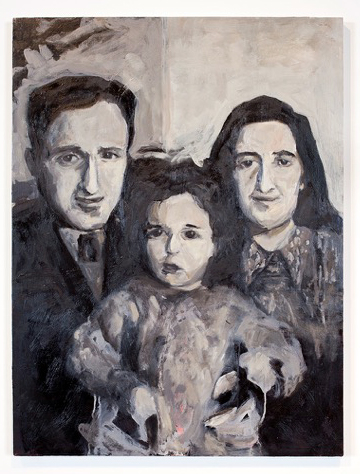

Auguste Rodin, French, 1840-1917, Large Hand of a Pianist, modeled 1885, Musee Rodin, cast 9, 1969

Rodin possessed an uncanny knack for creating emphatically expressive sculpture, even when the sculpted forms were merely a clutching hand or straining torso. They surge with energy, and the surfaces of his figures were left calculatedly rough, so as to catch the light and imbue a sense of movement. They need to be seen in the round, and, thankfully, nearly all the works on view are thoughtfully displayed for viewing from multiple sides.

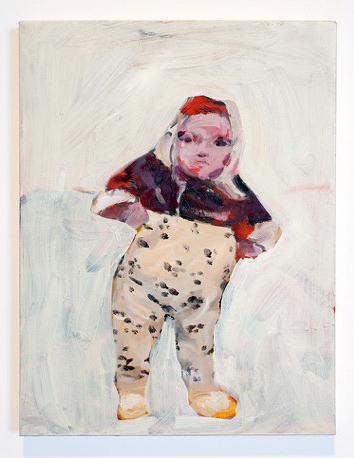

Auguste Rodin, French, 1840 – 1917, Narcisse, modeled about 1882,enlarged and retitled 1890; Musée Rodin, cast 8/8 in 1985, Bronze, 32 × 13 × 12 1/4 inches. Lent by Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Foundation.

The exhibition comfortably fills the spacious Hodge Galleries with works both large and small. Some of the most interesting sculptures, in fact, are the wispy, diminutive studies Rodin made—never intended for display—which reveal how he worked out compositional problems. These offer a glimpse at his working process.

The Gates of Hell was his breakout masterpiece, and the teeming cascade of figures which writhe on its surface served as inspiration for many of his subsequent works, like The Thinker, which in its original state, was perched high on the doors, meditatively and dispassionately contemplating the inferno below.

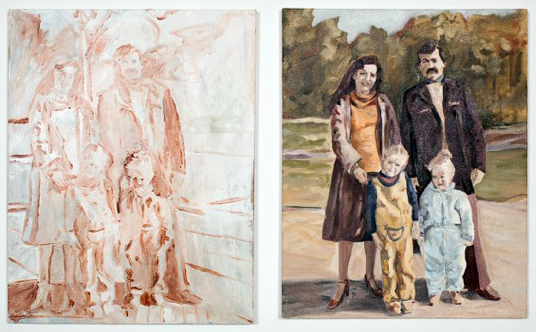

Auguste Rodin, French, 1840 – 1917, Three Faunesses, modeled before 1896; Musée Rodin, cast in 1959, cast number unknown, Bronze, 9 1/4 × 11 1/2 × 6 1/2 inches. Lent by Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Foundation.

Several studies for Rodin’s triumphant posthumous monument to Balzac are on display; one of his most iconic works, Rodin obsessed about getting the likeness correct, going so far as to arrange for Balzac’s tailor to make a suit of Balzac’s dimensions; this was worn by a model who was a dead-ringer for the author himself. In the end, though, Rodin sculpted Balzac shrouded the monk’s robe he famously wore as he wrote.

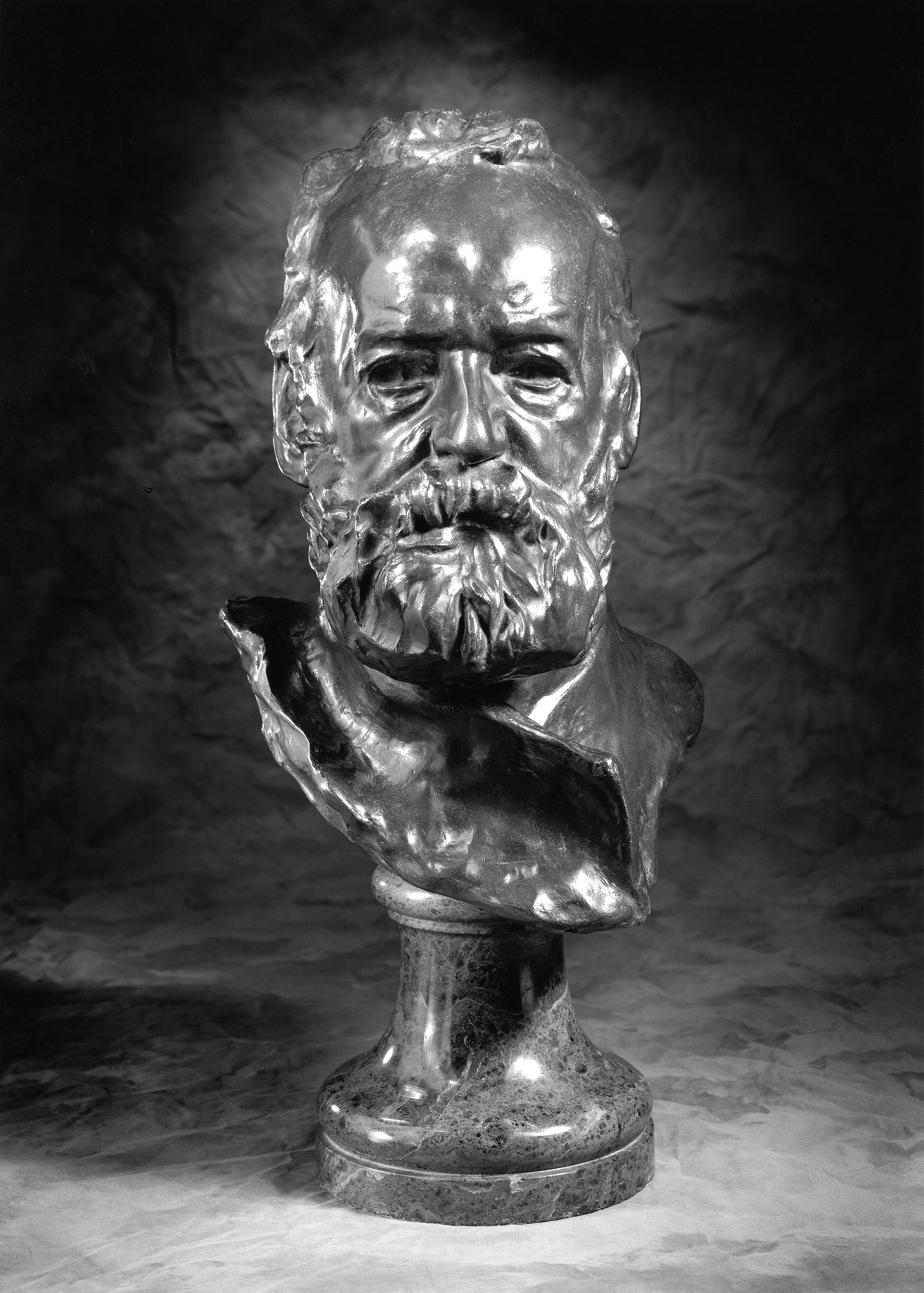

Auguste Rodin, French, 1840 – 1917, Bust of Victor Hugo, modeled 1883; cast number and date unknown, Bronze, 17 × 10 1/4 × 10 3/4 inches. Lent by Iris Cantor

There are several studies for the Burghers of Calais, a project that now seems ideally suited for Rodin, though it was poorly received at its unveiling. The emotionally charged ensemble depicts a group of citizens of Calais about to sacrificially offer themselves to the English, who during the Hundred Years War, had laid siege to the city. Each man reacts differently; one, clasping his head, seems distraught. On the face of another we read steely determination. Their entire bodies viscerally respond to the emotional weight of certain death, and the ensemble allowed Rodin to fully explore sculpture as a vehicle for expressing emotion.

Auguste Rodin, French, 1840 – 1917, Fallen Caryatid with Urn, modeled 1883, enlarged 1911-17; Musée Rodin, cast 4 in 1982, Bronze, 45 1/4 × 36 3/4 × 31 1/8 inches. Lent by Iris Cantor.

When Sixteenth Century art historian Giorgio Vasari described Michelangelo’s sculptures as terribilita (“terrible,” in English), he certainly wasn’t insulting them; the word then meant what we might today describe as “awesome,” like a fearfully powerful thunderstorm. It’s hard not to experience a streak of the same sensation as you stand in these rooms full of Rodin’s sculptures; they’re absolutely sublime. The forty-five works which comprise this exhibition are an infinitesimally small fraction of Rodin’s prodigious output; nevertheless, they’re more than enough to support the assessment, made by many, that Rodin was, without question, the greatest sculptor of his time.

Flint Institute of Art This exhibition has been organized and made possible by the Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Foundation. On exhibition through July 30, 2017