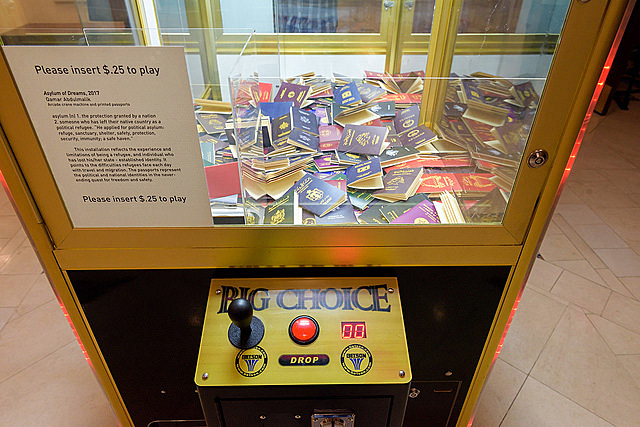

Installation Image, Sandwich Project, image courtesy Cynthia Greig 2017

“The Sandwich Project” at the Art Gallery of Windsor centers around famed American artist Martha Rosler’s 1974 video, “Semiotics of the Kitchen,” a visionary send-up of the entrapment of women in the machinery of the kitchen. It features a very young Rosler parodying more famed cooking show host Julia Childs.

After more than forty years, and our global digital brain transplant, the six-minute B&W video remains mesmerizing both intellectually and as a performance. With deadpan facial and bodily gestures, Rosler punctuates an alphabet of the accouterments of cooking — Apron, Bowl, Chopper, Dish, Egg Beater — objects that traditionally have signified women’s domestic identity, but become as sinister as the crippling machinery of the factory.

As Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp had been pushed over-the-edge by the machine of the factory in his 1936 film Modern Times, thus defining the generation of pre-union, factory workers, Rosler’s Julia Childs dramatizes the enslavement of women in the signifying machinery of the kitchen.

Rosler’s video, however, is only a set-up for the rest of the engaging Sandwich Project, which was the brainchild of Windsor’s renowned Iain Baxter&, an early conceptual artist, painter and photographer, and was curated by Art Gallery of Windsor’s Jaclyn Meloche, also an artist, performance artist and writer. Baxter& conceived the Sandwich project as a play on “all things Sandwich,” to quote Katherine Mastin, AGW’s Director,

Sandwich, one of the earliest neighborhoods in Windsor, namesake of England’s once important port, was the origin of the name for the portable lunch, which (after the Fourth Earl of Sandwich) like this exhibition, composes layers of ingredients (often between two slices of bread). The word dredges up all kinds of history both in England and in Windsor, in the underbelly of which lies the War of 1812, a conflict that to some locals seems as though it was between Detroit and Windsor. In fact, Sandwich, Ontario was the site of important 1812 battles.

Iain Baxter&, “Iain Baxter as an open-faced sandwich” 1978

Iain Baxter&, born in England, his own art fraught with visual hi-jinks, was obviously quite cognizant of this back story in conceiving the project, which is ripe with delicious visual puns and ironies.

Likewise it’s the relationship of food to social and political history, popular culture and feminism, that Meloche ran with to create six independent exhibitions, each of which is self-contained, with moments of delightful humor and brilliant art, while at the same time executing an engaging critical perspective on food and culture. A video entitled “Food as Metaphor,” moderated by Meloche, which includes statements and discussion by the artists, punctuates the exhibitions.

Baxter&’s own contribution, entitled “Baxter&Food,” is a collection of more or less still-life photos of nourishment. “Iain Baxter as an open face sandwich,” c.1978, is typical of his dadaistic play with art history in which he humorously features himself as both the maker and material of art. Equally the dada irony looms huge in “Still Life with Winter Vista,” 1996, which features a glass patio table laden with a cornucopia of tropical fruit and vegetables, with a classic Lake St. Clair winter landscape in the background. Baxter&’s energetic art prompts thinking about big issues like ecology, food and identity, rather than simply art stuff, yet at the same time his work has a subtle aesthetic valence that is hard to categorize. His “The Primaries,” composed of bottles of ketchup, mustard and blue Gatorade that he classifies as “found objects,” is not only a great commentary on our food culture and its ironic spectacality, but a rather wonderful conceptual sculpture.

Iain Baxter&, “The Primaries,” Found Objects, 2017

Of the six exhibits in The Sandwich Project, the one most provocative to the central issue of our food culture is “Food, Feminism and Kitchen Culture.” Introduced by Rosler’s video, the exhibition sets up a discourse on the landscape of the kitchen as an imprisoning construction of which women are the principle inhabitants.

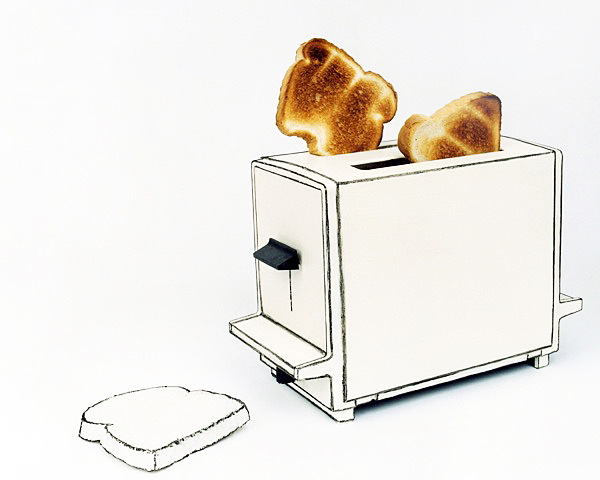

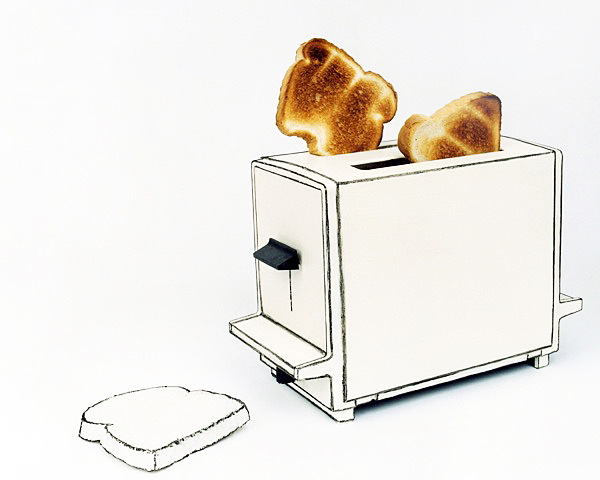

Cynthia Greig, “Representation no. 29 (toaster), chromogenic print, 20 x 24”

If Rosler’s video sees the objects of the kitchen as an almost violent lexicon of possibilities for the construction of women’s identity —Apron/Women, Bowl/Women, Chopper/Women, Dish/Women — Cynthia Greig’s (Detroit’s best kept secret) manipulated photographs become escapes from the reality of the haptic world into a realm of diagrammatic ghosts, from realism to shadows of the real. In reducing photographs of common objects of the kitchen — toaster, milk cartons, coffee cups, French fry carton — to elemental outlines, they become ideas that hold us captive. These graceful, elegant shapes become enigmatic containers that define and thus limit — limitations to being, to exuberance, and diagrams that ultimately beckon language to elucidate and emancipate them.

Each of Greig’s diagrammatic images includes a referent to reality. A diagrammed toaster has images of freshly “toasted” bread popping out of it. The outlined milk carton has “spilled milk” next to it. A French fry carton has French “fried potatoes” sticking out of it. Each photograph posits the philosophical dilemma of what contains and what is contained. Pushed to their logical end, these images become a sort of dictatorial grammar of the kitchen.

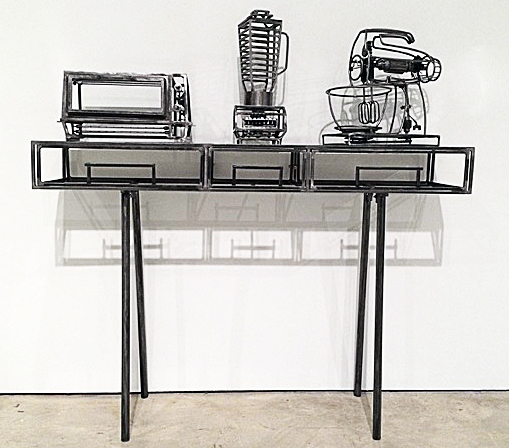

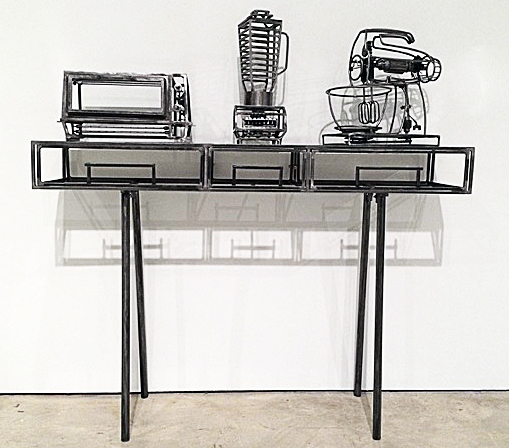

Anna Frlan, “Kitchen as Factory [Mixing machine, blending machine,toasting machine]”, Steel, 2017

Complementing Greig’s skeletal works are Anna Frlan’s welded steel replicas of kitchen appliances. Actually, as if taking a hint from Greig’s diagrammatic images, Frlan’s are even more cage-like machines — a toaster oven, a blender, a mixer, a stove, a dishwasher. These drawings made of steel, at the same time as they resemble medieval torture devices, might suggest Piranesi’s images of Roman prisons. They are stunning, sinister signifiers of the role of kitchens in defining identity.

Each of the artists in this section of The Sandwich Project makes a stunning contribution to the discourse on Food, Feminism and Kitchen Culture. Marilyn Minter’s painting from her “Food Porn” series and Carly Erber’s crocheted “Salisbury Steak” make wonderfully opposite statements about women and representation of food. Christiane Pflug’s painting “Kitchen Door with Ursula,” 1966, and Annie Pootoogook’s “Tea Drinkers,” 2001, both reflect subtle personal takes on the complex psychology of kitchen life.

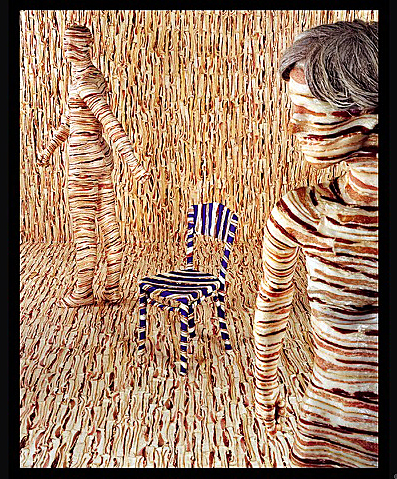

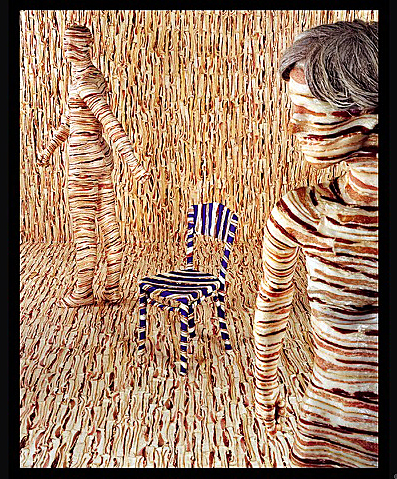

Sandy Skoglund, “Body Limits,” 1992

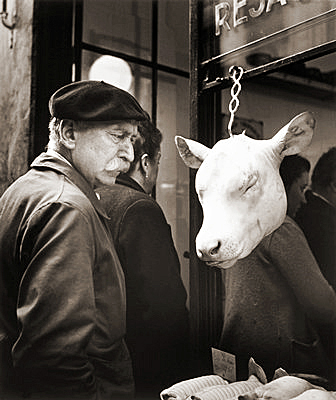

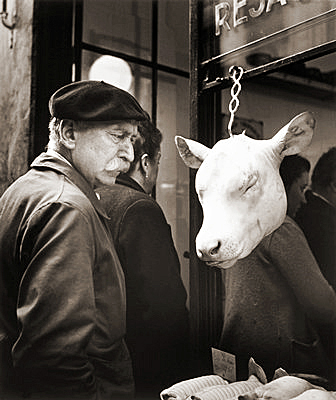

A related, borrowed exhibition, originating at the Akron Art Museum and curated by Theresa Bembnister, “Snack” is a tour de force of a generous selection of diverse representations of food, featuring Pop artists Andy Warhol, James Rosenquist, Claes Oldenburg and other contemporary artists’ takes on the western recreational activity of food and eating. Sandy Skoglund’s “Body Limits” documents a surreal tableau she created parodying a fashion shoot of two figures dressed in bacon. French photographer Robert Doisneau’s “L’Innocent,” 1949, captures a typical Parisian gentleman’s existential encounter with his dinner in the window of a restaurant.

Robert Doisneau, “L’Innocent,” B& W Photograph, 1949

The Sandwich Project is no less than a blockbuster of an exhibition, a realization that surpasses expectation. The fourth part, “Lunch,” collects a wonderful assortment of artifacts and images of the great pastime of noonday culture, including a wall full of school kids’ lunch boxes that in themselves are a history of midcentury pop culture, and a selection of early twentieth-century images from The Henry Ford Museum archives of Detroit cafeterias, diners, and hot dog stands.

Frederick Arthur Verner, “Untitled (River Scene, Sunset”), 1891, watercolour over graphite on paper

Two other exhibitions that bookend The Sandwich Project are AGW’s collection of nineteenth-century watercolors of the Sandwich area by artist Frederick Arthur Verner, and “Food and Film,” which features four short films on the production and distribution of food as a go-between in signifying Canadian identity. One of Verner’s watercolors features the Detroit River-front with typically English village-like architecture of early Windsor (Sandwich) in the foreground, replete with fishing boats, and a nascent Detroit industrial landscape on the far shore. During the nineteenth century, the Detroit River was famous for its astonishing fishing, supplying First Nation people and eventually Windsorites and Detroiters with bounteous whitefish and walleye. Verner’s watercolor thus becomes an ironic commentary on the devolution of food production in the area.

The Sandwich Project is a perfect summertime day trip or even two-day trip, and yields an abundance of food-for-thought about the business, culture, and representation of our relationship with food. For lunch, Sir Cedric’s Fish and Chips is right around the corner from the Art Gallery of Windsor, reminding us of the Canadian predilection for things British. If, however your tastes are more inclined to American fare, there’s Lafayette Coney Island just across the border.

The Sandwich Project Continues through October 1, 2017

Art Gallery of Windsor, 401 Riverside Drive West, Windsor, Ontario N9A7J1 519-977-0013