Brush with Reality: Yigal Ozeri at the Flint Institute of Arts

“Brush with Reality: Yigal Ozeri” at the Flint Institute of Arts through Jan. 2, is a career retrospective of the painter’s large-scale, striking portraits that read like photographs. It’s a handsome, accessible exhibition that makes for a good introduction to the FIA, if you’ve yet to visit, located in a polychrome modern building in Flint’s Cultural Center.

The temptation is to call the Israeli-born Ozeri’s work “photorealist,” but it’s a term the artist, who’s lived and worked in New York City for years, doesn’t apply to himself – never mind his admiration for the genre.

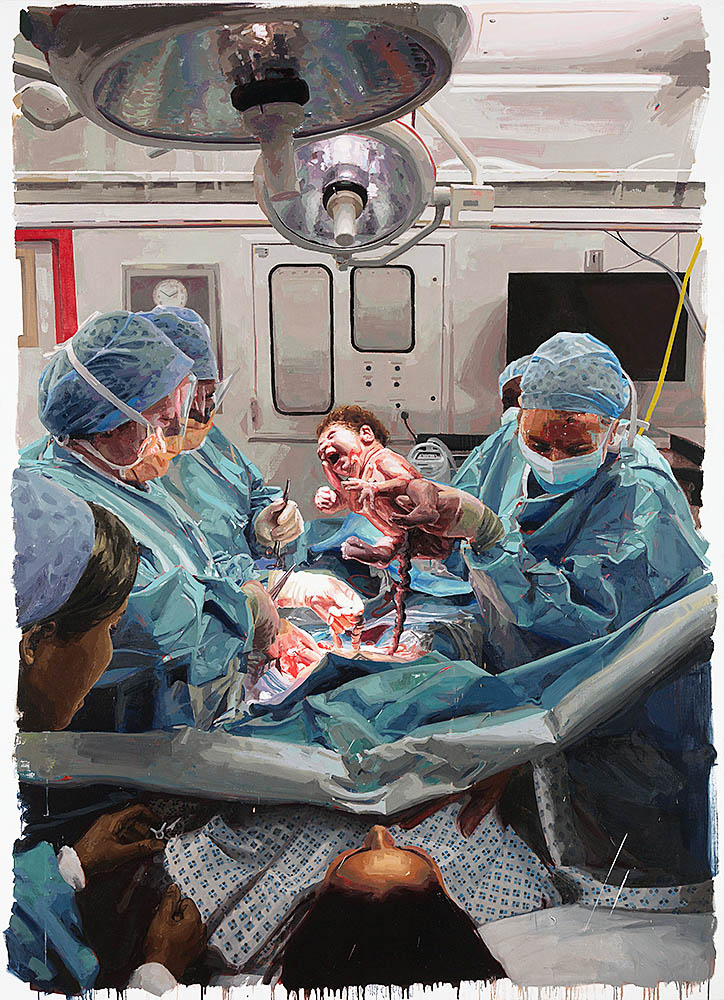

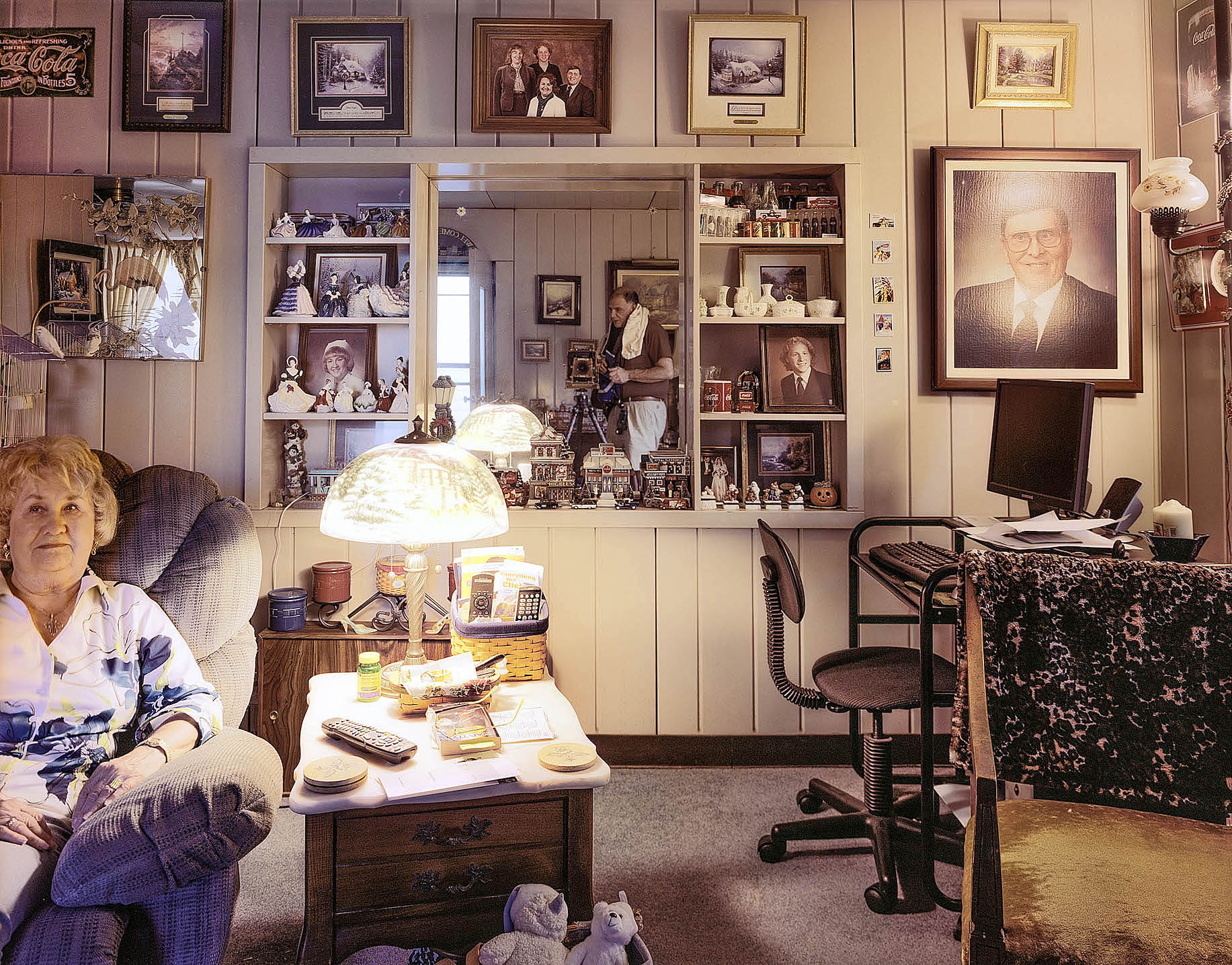

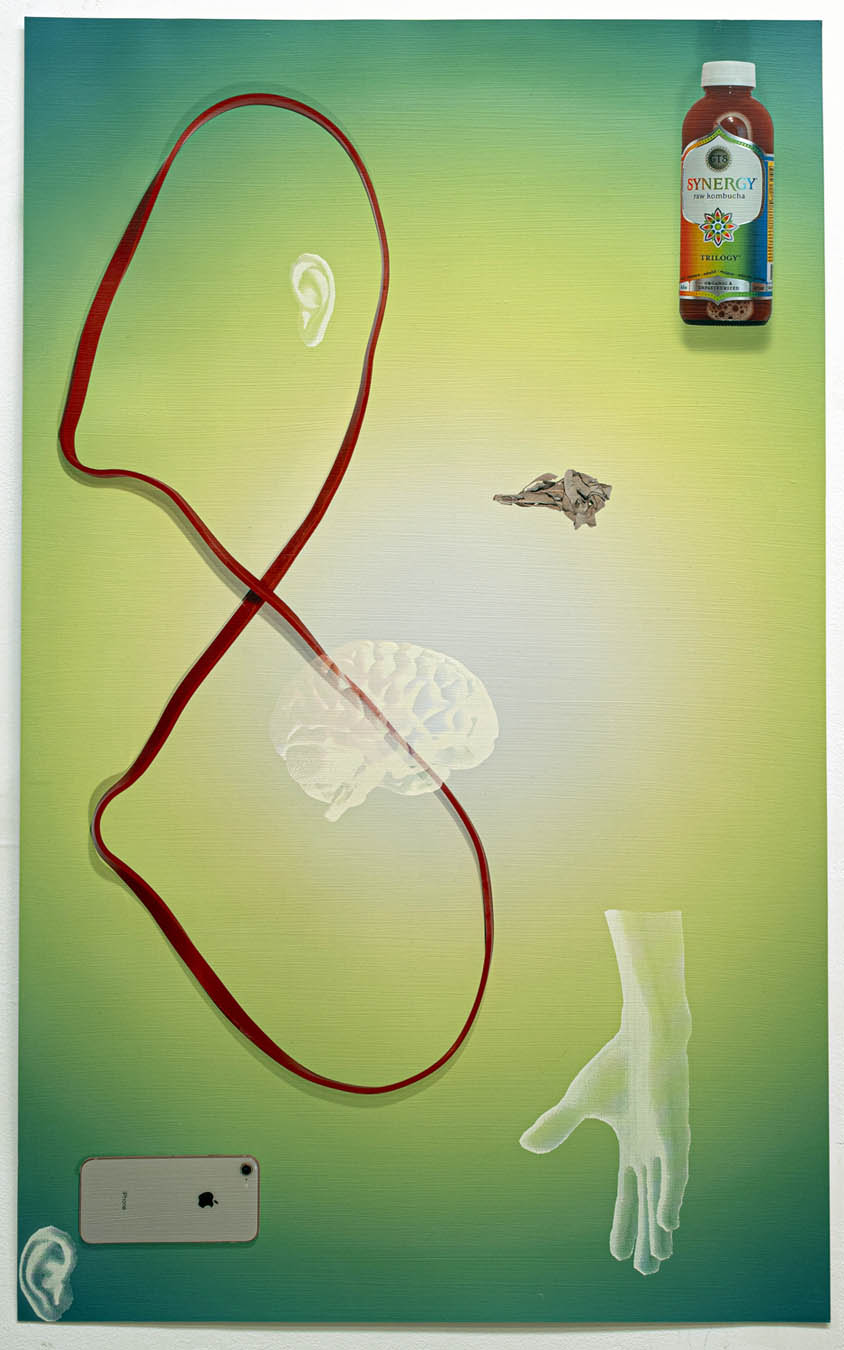

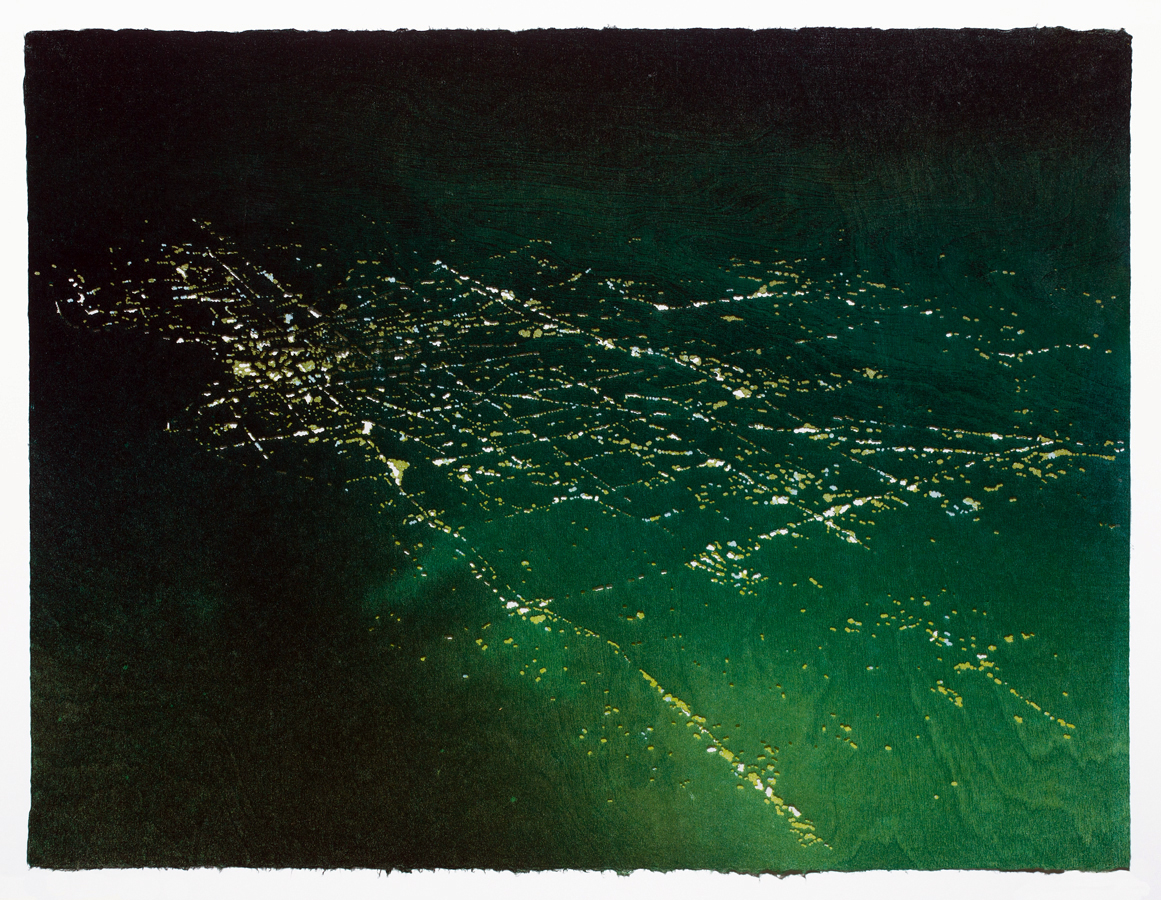

“Brush with Reality: Yigal Ozeri” at Flint Institute of Arts, All images by Michael H. Hodges

Ozeri, with works in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Israel Museum, among others, deliberately deviates from the photorealist playbook. “He said he wants to deconstruct photography,” says Tracee J. Glab, FIA curator of collections and exhibitions who organized the show. “It all starts with the photographs,” she adds, mostly taken by the artist’s daughter, “but from there he then decides what parts he wants to make precise and hyper-realistic, and what parts more soft-focused and impressionist.” Additionally, Ozeri’s work stands out in another significant way – most photorealist painters focus on inanimate objects and symbols of modernity like cars, roadside diners, or California swimming pools. Few do people.

The result is a collection of canvases of remarkable depth and technical skill. Over half the gallery space is given to the artist’s trademark portraits of pretty young women in landscapes – more on that in a moment — with the rest drawn from a series of urban New York scenes.

Among the latter, the 2018 “Untitled; Cristal” features a somber, young African-American woman in a full fur coat in the middle of a Manhattan avenue, staring straight at the viewer — typical of much of Ozeri’s portraiture. It’s part of the composition’s power that it both conveys a strong sense of the subject’s character, as well the impression that New York City on either side of her is hurtling at you full blast.

Yigal Ozeri, Untitled; Cristal, 2018, oil on canvas, Collection of the Artist, NJ.

The painting is curator Glab’s favorite among the New York series. “With the distortions on either side of her,” she says, “it really captures what it’s like to be in New York City, overwhelmed.”

One of the most hyper-realist treatments is “Lizzie in the Park.” Take a good look at the cascade of blond and brown hair falling out from her black hood. You read precisely how it would feel to the touch. It’s a minor detail in its way, and yet the one that totally makes the painting – and one you can hardly take your eyes off. By contrast, the snowy, woodsy background behind her is all low depth of field. Was that the nature of the actual photograph, or has the artist softened things to make the subject pop? You decide.

Yigal Ozeri, Lizzie in the Park, 2010, oil on paper, Collection of Wayne F. Yakes, MD.

But not all of Ozeri’s portraits come with such a sharp focus. With “Untitled; Olya” from 2015, the young woman on a wind-swept beach is rendered in soft focus, which in this case adds a certain urgency. And if you look closely, the remarkable brushwork almost creates three dimensions out of two. It’s a gorgeous image, yet one that calls to mind the inevitable questions of 2021 – in this case, whether it’s entirely seemly to stage an exhibition of pretty young women painted by a man born in 1958.

Yigal Ozeri, Untitled; Olya (detail), 2015. Oil on canvas, 54 x 80 in. Collection of Louis K. and Susan P. Meisel.

It’s an issue Glab freely admits she pondered. “I definitely questioned that as a woman and feminist,” she says. “I asked Ozeri – why women? And his answer was that he felt he was depicting their power.” Additionally, he told her all the models are paid, and while Ozeri picks the locations, from city streets to the Costa Rican jungle, the models (occasionally men) choose how they want to be depicted – whether lying in shallow water in a stunning red dress as with 2012’s “Untitled; Territory,” or in a harvested field in “Untitled; COVID Wheat Field” from last year.

“I liked that answer,” Glab said. And she’s also solicited feedback from visitors, none of whom have had any complaints. Glab thinks this is in part because while the gaze is indisputably male, it’s neither exploitative nor condescending. These women, gorgeous though they all may be, are presented as individuals with force and power and not as pin-ups. Their direct stares challenge us to imagine they were anything but knowing and willing participants in this process.

Breaking the mold in part because of its strong emotions is the aforementioned “Untitled; COVID Wheat Field.” A young black man in a sweater and face mask has collapsed, seemingly ecstatic, in an autumnal field. Under a glowering sky, he radiates unexpected delight and joy – a contrast to Ozeri’s mostly sober, enigmatic women. Indeed, while the season around him is all wrong, the subject personifies the giddy rapture so many of us felt early this summer when liberty seemed at hand before the Delta variant really started to bite.

Yigal Ozeri, Untitled; COVID Wheat Field, 2020. Oil on canvas. Doron Sebbag Art Collection, ORS Ltd., Tel Aviv.

Included within the New York series, though completely out of place geographically, is a portrait of a cheerful guy in a lavishly decked out Israeli candy store in 2019’s “Untitled; A Tel Aviv Story” – and his American analogue running a candy-packed, Manhattan kiosk in “Untitled: A New York Story,” also from 2019. But for those who adore the gritty romance of the Big Apple, Ozeri’s nighttime painting of a New York intersection is particularly persuasive, with car headlights providing visual drama. It’s chock full of banal details from New York street life – the cars, the recently painted bike lane, the construction cones and the construction worker, the jaywalker, and the receding parade of eight-story buildings with lighted windows here and there marching toward the vanishing point. It’s enough to make the impressionable fall in love with New York all over again.

Yigal Ozeri, Untitled; New York, 2020. Oil on canvas. Collection of the Artist, NJ.

“Brush with Reality: Yigal Ozeri” will be up at the Flint Institute of Arts, which is free on Saturdays, through Jan. 2.