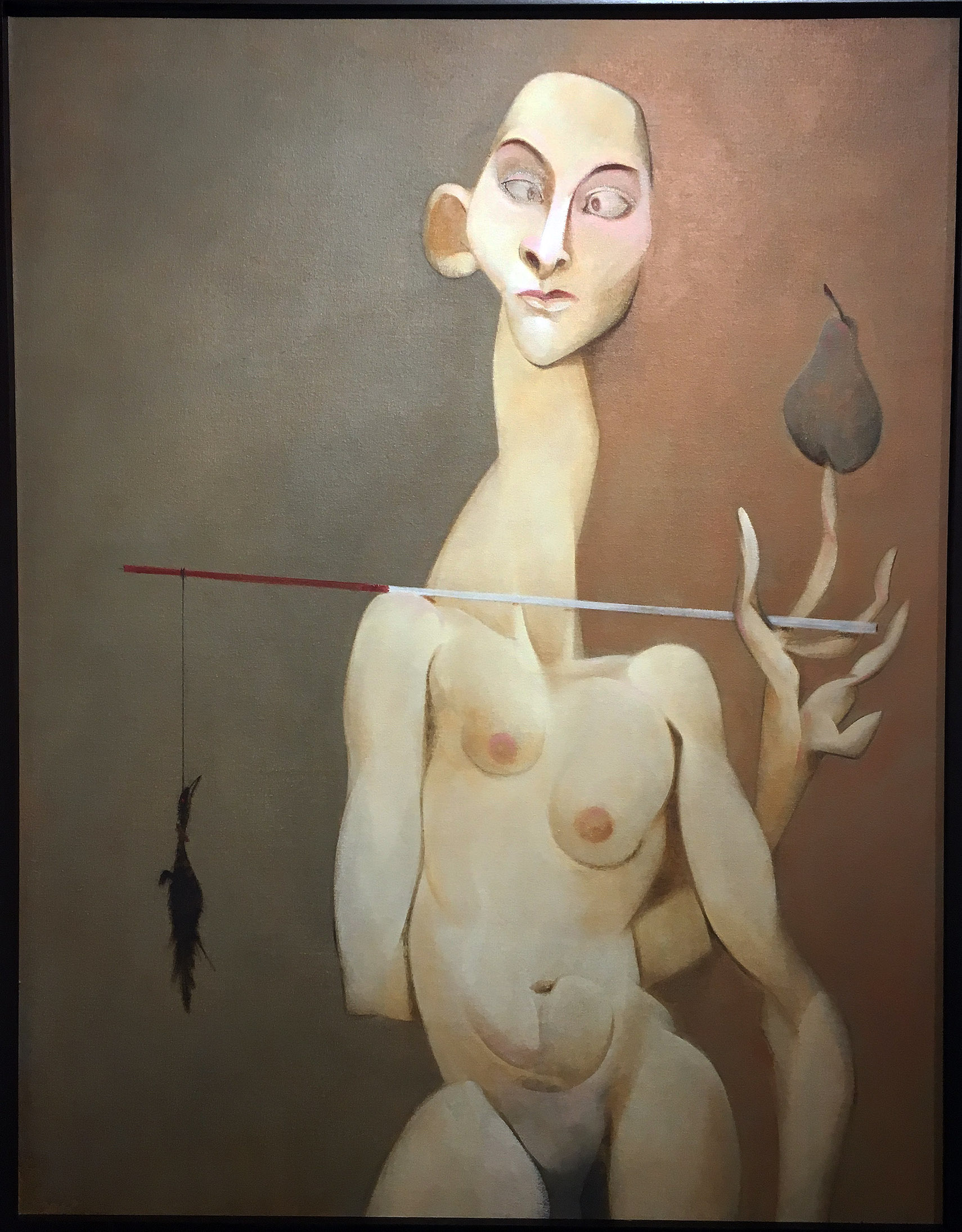

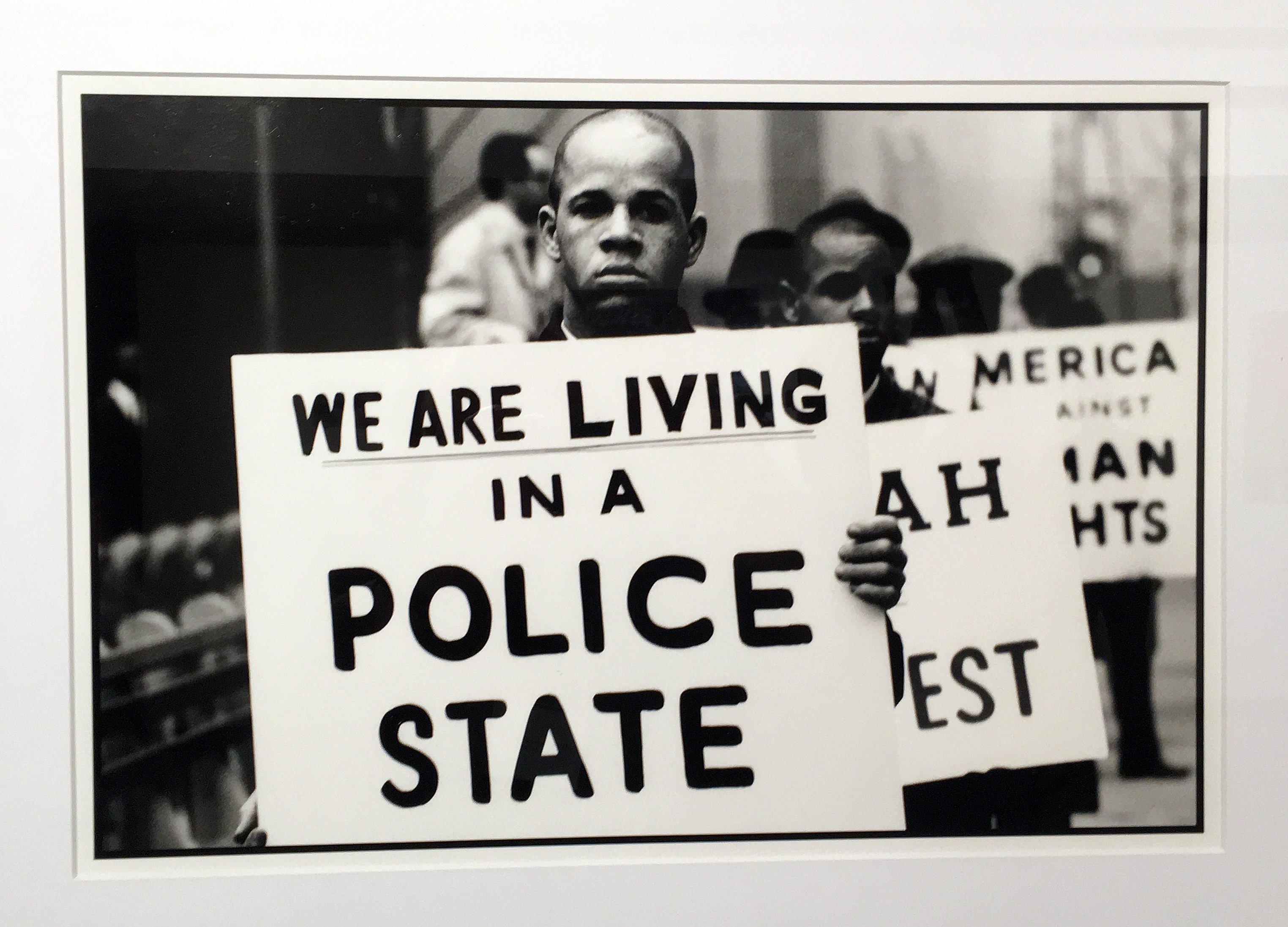

Installation view of Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, June 12–October 01, 2017. © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Jonathan Muzikar

The holdings of the Frank Lloyd Wright archive, jointly acquired by the Museum of Modern Art and the Avery Architectural & Fine Art Library at Columbia University in 2012, are vast—no surprise, since Wright’s career spanned a seventy-year trajectory. The archive’s holdings comprise 55,000 drawings, 125,000 photographs, and well over a quarter-million sheets of correspondence, not to mention models, architectural fragments, films, and other multimedia. If the celebrated 20th century architect were alive today, he’d be 150, and to commemorate his sesquicentennial the MoMA’s exhibition Unpacking the Archives presents over 400 works from the archives, offering an illuminating thematic and chronological survey of Wright’s career.

Installation view of Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, June 12–October 01, 2017. © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Jonathan Muzikar

The show’s title wittily puns on both the content of the exhibition, all gleaned from the newly-acquired archive, and on the show’s organization, for which twenty MoMA curators take an object of their choosing and explain (“unpack”) its relevance within the context of Wright’s career. This curatorial decision offers a refreshingly new approach to a survey of Wright, since some of his most iconic works (the Robie House, for example) are conspicuously absent, and viewers are introduced to some of Wright’s lesser known projects, such as his unrealized plans for Rosenwald School and his utopian Davidson Little Farms Unit.

Each of the exhibition’s fourteen galleries focuses either on a specific theme (ornament, ecology, circular geometries, and urbanism, to name a few) or an architectural structure (starting with the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo and culminating with the Guggenheim). Some gallery spaces reinforce some of Wright’s most characteristic attributes, such as his compulsive obsession with total design. Not content to merely design a structure, Wright famously maintained absolute control over all the interior furniture and furnishings, going so far as to show up uninvited on the doorsteps of prior clients to ensure sure that the totality of his interior design scheme remained unaltered.

Other galleries playfully stray from the conventional narrative arc of Wright’s career. One room, devoted to studio drawings, displays drawings by Wright’s own hand juxtaposed with drawings from studio assistants, making the point that the studio’s more refined and aesthetic “perspective drawings” were generally rendered by specialists, such as the manifestly talented Marion Mahony. Perhaps the most surprising and satisfying original drawings on view, simply because they burst with spontaneity, were the sketches Wright made on a napkin as he was working out some design problems posed by his mile-high skyscraper.

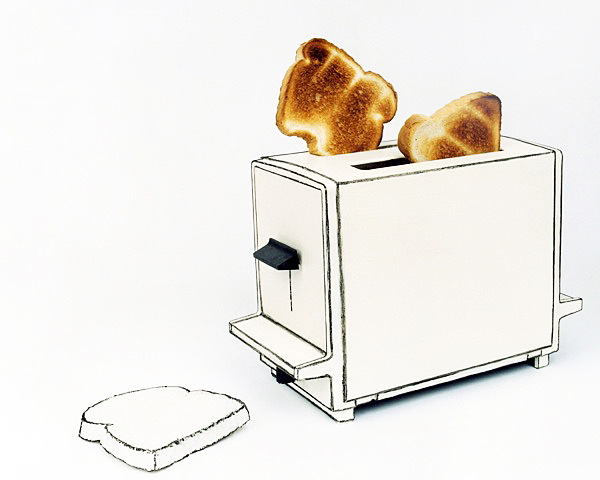

Frank Lloyd Wright (American, 1867–1959). Fallingwater (Kaufmann House), Mill Run, Pennsylvania. 1934–37. Perspective from the south. Pencil and colored pencil on paper, 15 3/8 × 25 1/4″ (39.1 × 64.1 cm). The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York) © 2017 Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale, AZ. All rights reserved

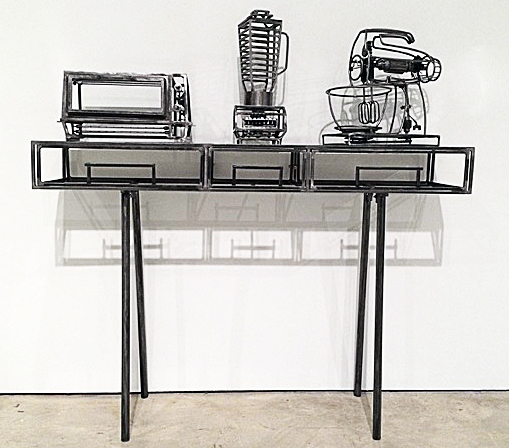

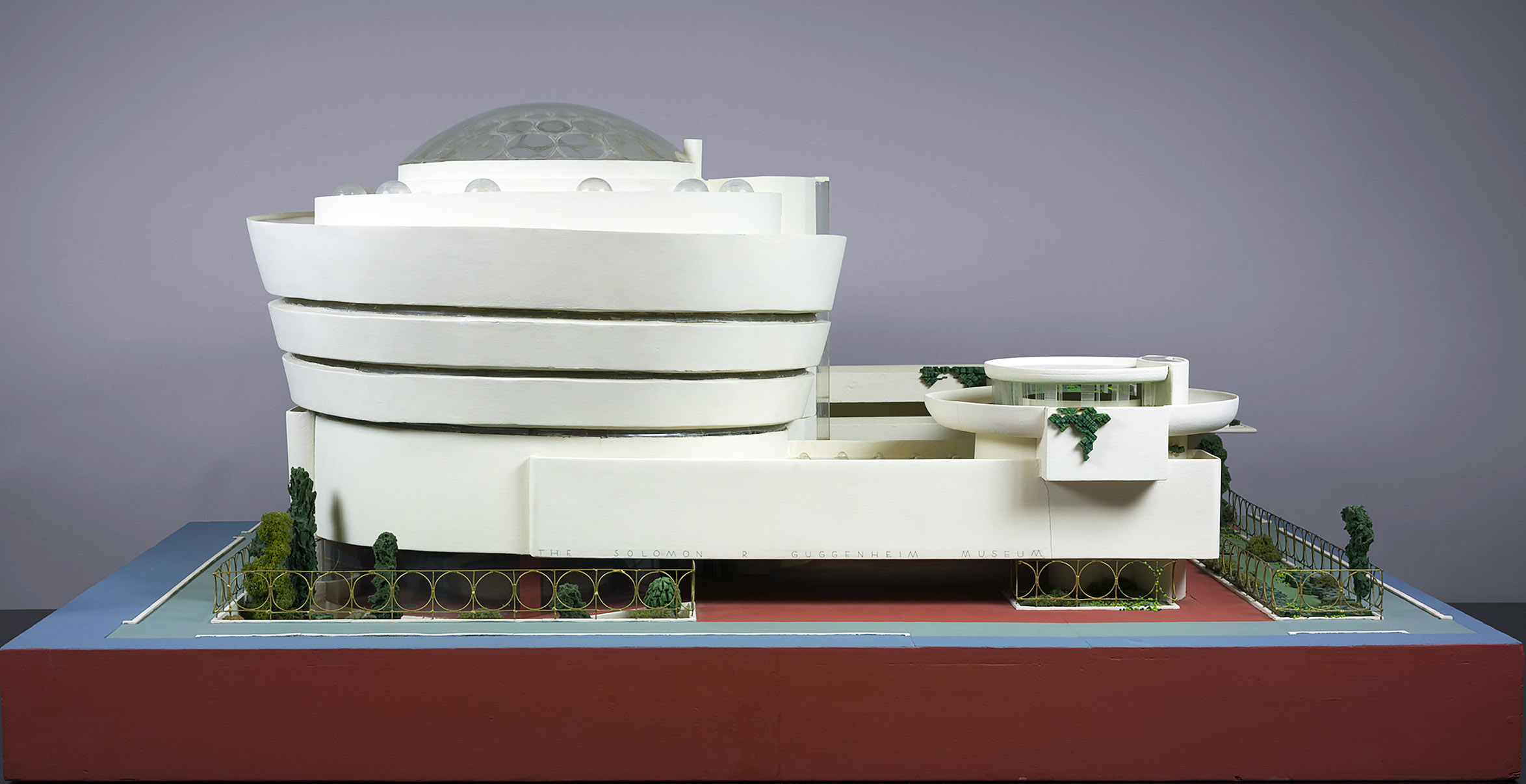

The exhibition is heavy on two-dimensional architectural layouts, floorplans, and perspective drawings, but there are also some examples of the furnishings Wright’s studio created, ranging from art-glass windows, furniture, tableware, rugs and drapery. Also on view are the elaborate sculptural models Wright produced to help pitch ideas to his clients. These include a model of his iconic Guggenheim, flanked by an early perspective-rendering of the building, reminding us that the structure was once to have been an alarmingly garish pink.

Frank Lloyd Wright (American, 1867–1959). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. 1943–59. Model. Painted wood, plastic, glass beads, ink, and watercolor on paper, 28 x 62 x 44″ (71.1 x 157.5 x 111.8 cm). The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York) © 2017 Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale, AZ. All rights reserved.

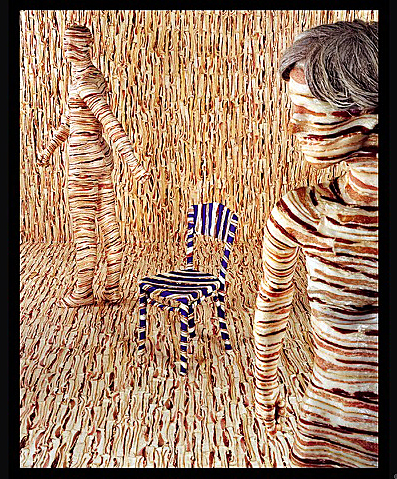

Wright at 150 directly acknowledges Wright’s Michigan connection in its display of an elaborate layout Wright drafted for Kalamazoo’s Galesburg Community, known as “The Acres,” originally to contain a network of homes on twenty-one circular-shaped lots, though in the end only four were built. The exhibition also devotes significant space to his Usonian homes, the comparatively inexpensive do-it-yourself (in theory, anyway) home-kits Wright’s studio produced, intending to make quality architecture available to the middle class; the Detroit area boasts of three such homes: the Turkel House (Palmer Woods), the Smith House (Bloomfield township), and the Affleck House (Bloomfield Hills). And some of Wright’s textile patterns on view (such as his March Baloons, depicting an elaborate network of intersecting circles) have been adopted by Ann Arbor’s Motawi Tileworks, which produces a handsome line of Wright-inspired ceramic decorative tile.

Frank Lloyd Wright (American, 1867–1959). March Balloons. 1955. Drawing based on a c. 1926 design for Liberty magazine. Colored pencil on paper, 28 1/4 x 24 1/2 in. (71.8 x 62.2 cm). The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York) © 2017 Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale, AZ. All rights reserved.

Spread across a generous suite of galleries on the MoMA’s third floor, this exhibition at first glance seems perhaps austere (just one floor up, after all, are the reliably crowd-pleasing combines of Rauschenberg displayed alongside some of the zany 1970s kinetic works produced by the organization Experiments in Art and Technology). By contrast, Wright’s stately and geometric architectural plans on view in Unpacking the Archive seem emphatically cerebral, in some cases even displayed on mock-draft tables. But his ideas were revolutionary for his time, whether it be the need for sustainable architecture or for quality housing for all social classes, rather than just the proverbial 1%. And this cross-section of the Frank Lloyd Wright archive offers revealing and unprecedented access into the agile mind of an architect whose ideas remain uncannily relevant today.

Museum of Modern Art Exhibition runs through October 1, 2017