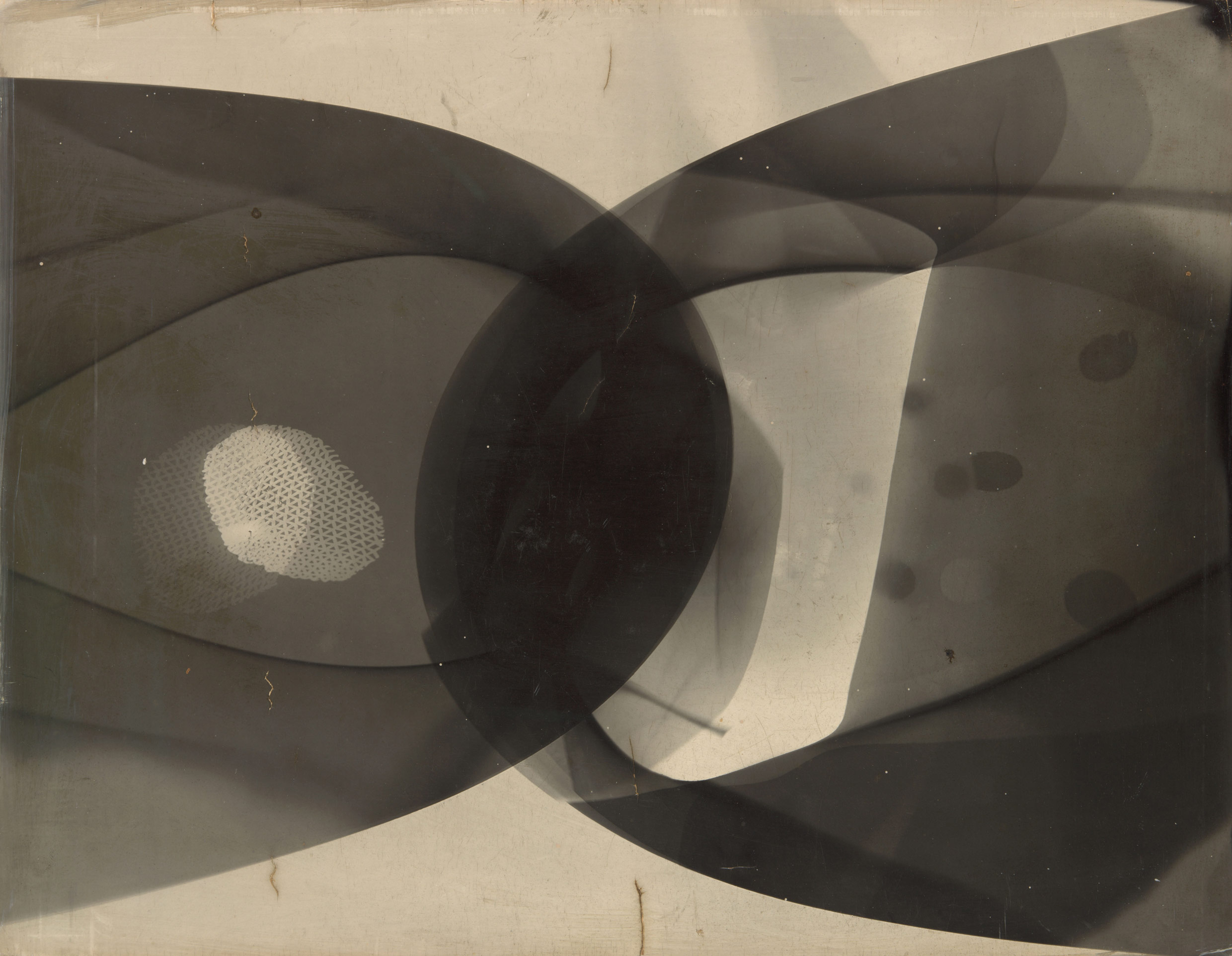

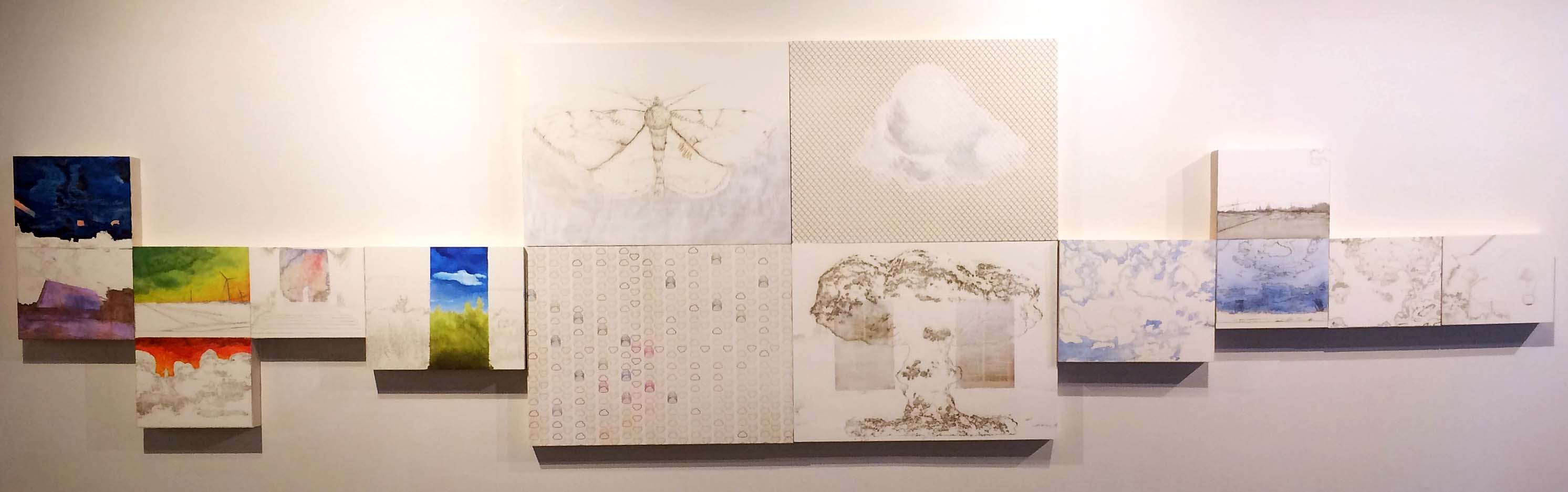

Cody VanderKaay, Installation image

Cody VanderKaay’s solo exhibition, Terrestrial Celestial, opened March 3, 2017, at the Oakland University Art Gallery, where Dick Goody, Art Chair, and curator at OUAG, turns inward to one of his associate professors to exhibit new work that takes the viewer in a variety of visual art directions. On the ground or in the sky, VanderKaay presents three-dimensional work that has delicacy as in the Orange Shed, versus blunt boldness, as in Six Views.

So where is this artist in his creative trajectory? I would say he is exploring an inner sensibility he has developed since his youthful years of art experience combined with his MFA at the University of Georgia, where he gives us his take on three-dimensional form.

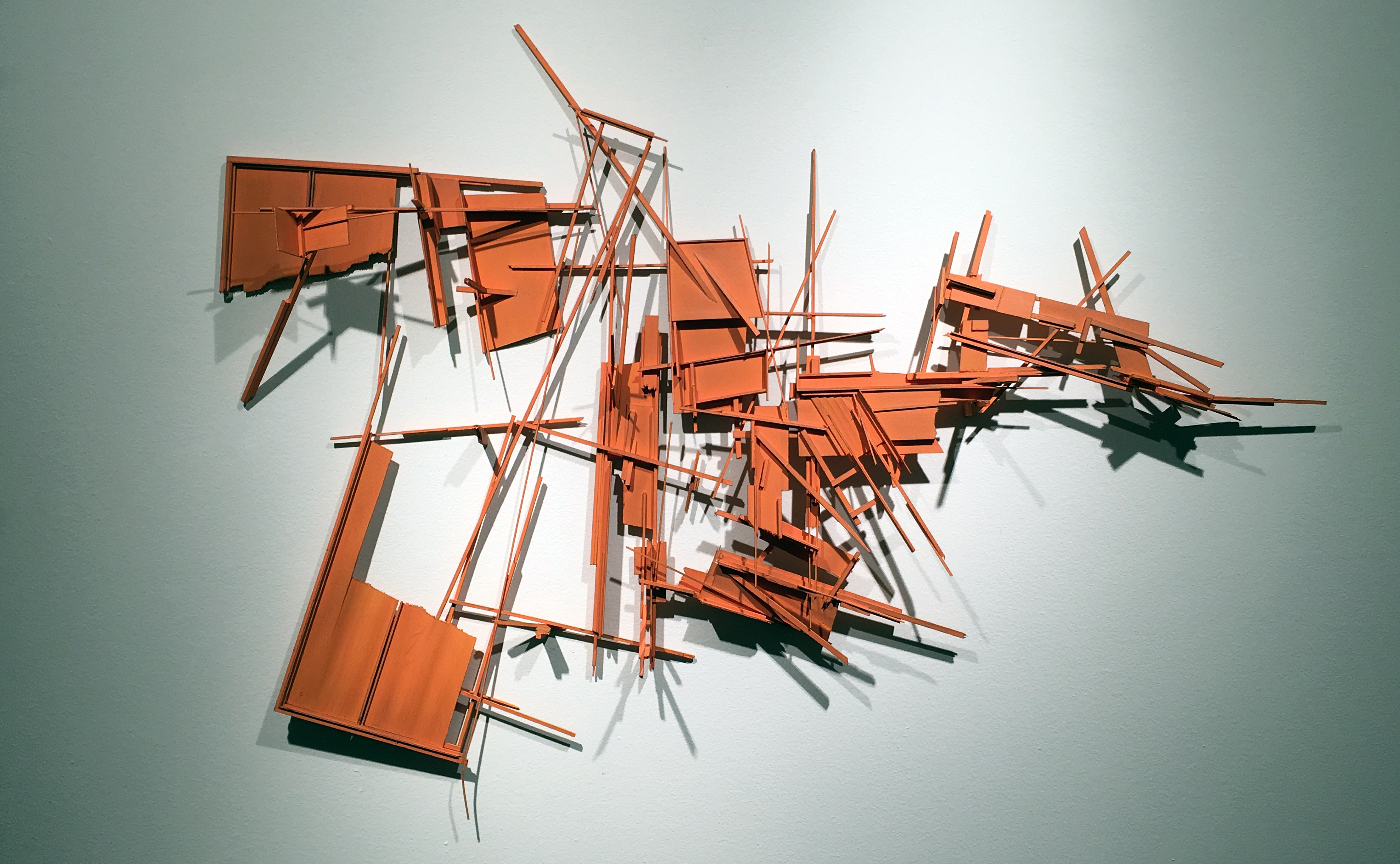

Cody VanderKaay, Orange Shed, Latex on Basswood, 2016

The delicate relief, Orange Shed, using basswood and latex, reminds me of relief work from the 1950’s in the United States that was mostly decorative, with the exception of an artist such as David Smith. Smith combined found objects, worked in metal based on his experience working in a car body shop. The shared element with VanderKaay’s work is largely based on Constructivism, a modern art movement that flourished in Russia, then moved to Europe during the early parts of the 20th century. The central concept is placing the priority on the material employed, versus the subject matter or motif. The materials to express an idea dictate the form. The fundamental analysis of the material leads to the function. This idea shapes VanderKaay’s other work as well.

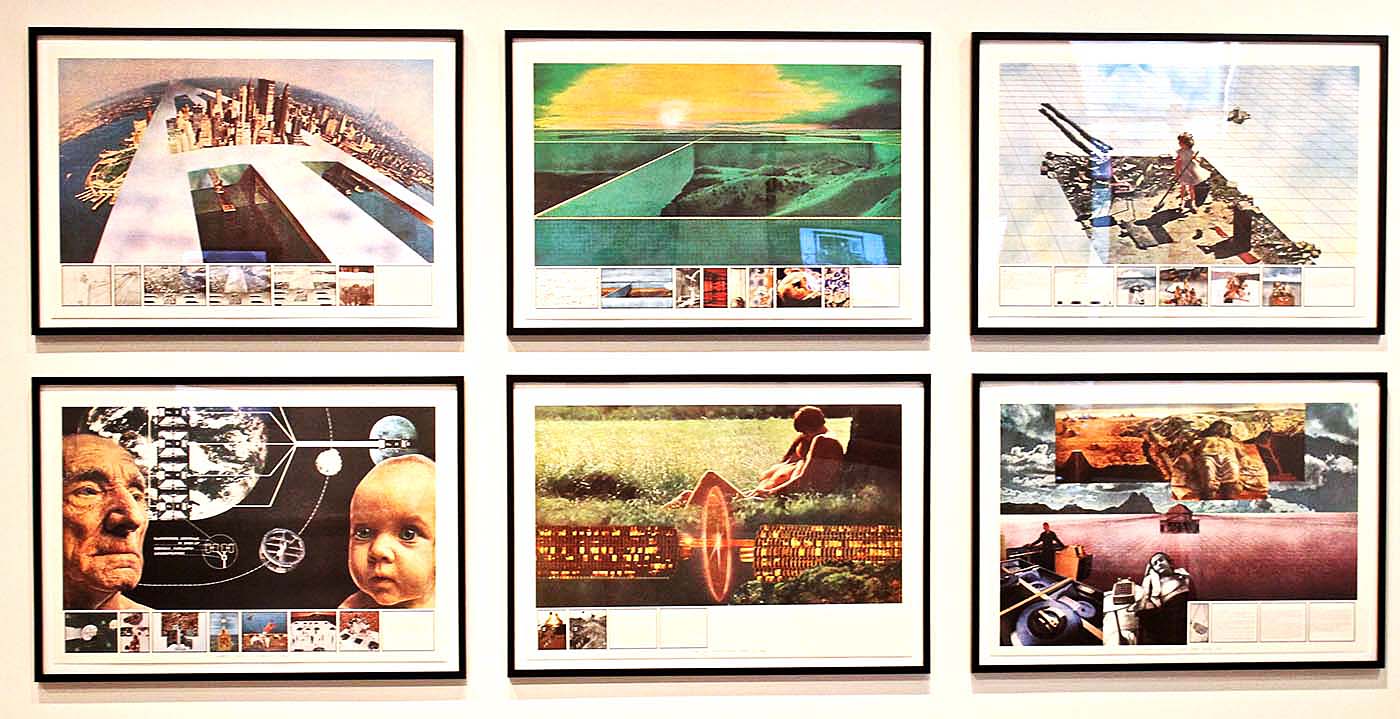

Cody VanderKaay, Six Views, Concrete 2017

Borrowing on ideas presented by Minimalist artists, be it Donald Judd or Robert Morris, the early 1980s brought a shift from Abstract Expressionism to a pared-down, three-dimensional object with little reference to real objects. The new vocabulary was simplified geometric forms created from humble industrial material. VanderKaay provides a repetition of nine “house-shaped” concrete objects in Six Views with an angled bottom that provides the observer with a parallel view. It would seem variations on this theme could produce a body of work on its own, as the aesthetics are pleasing, even comforting to the eye, whether it appears in relief or as a taped drawing on the wall.

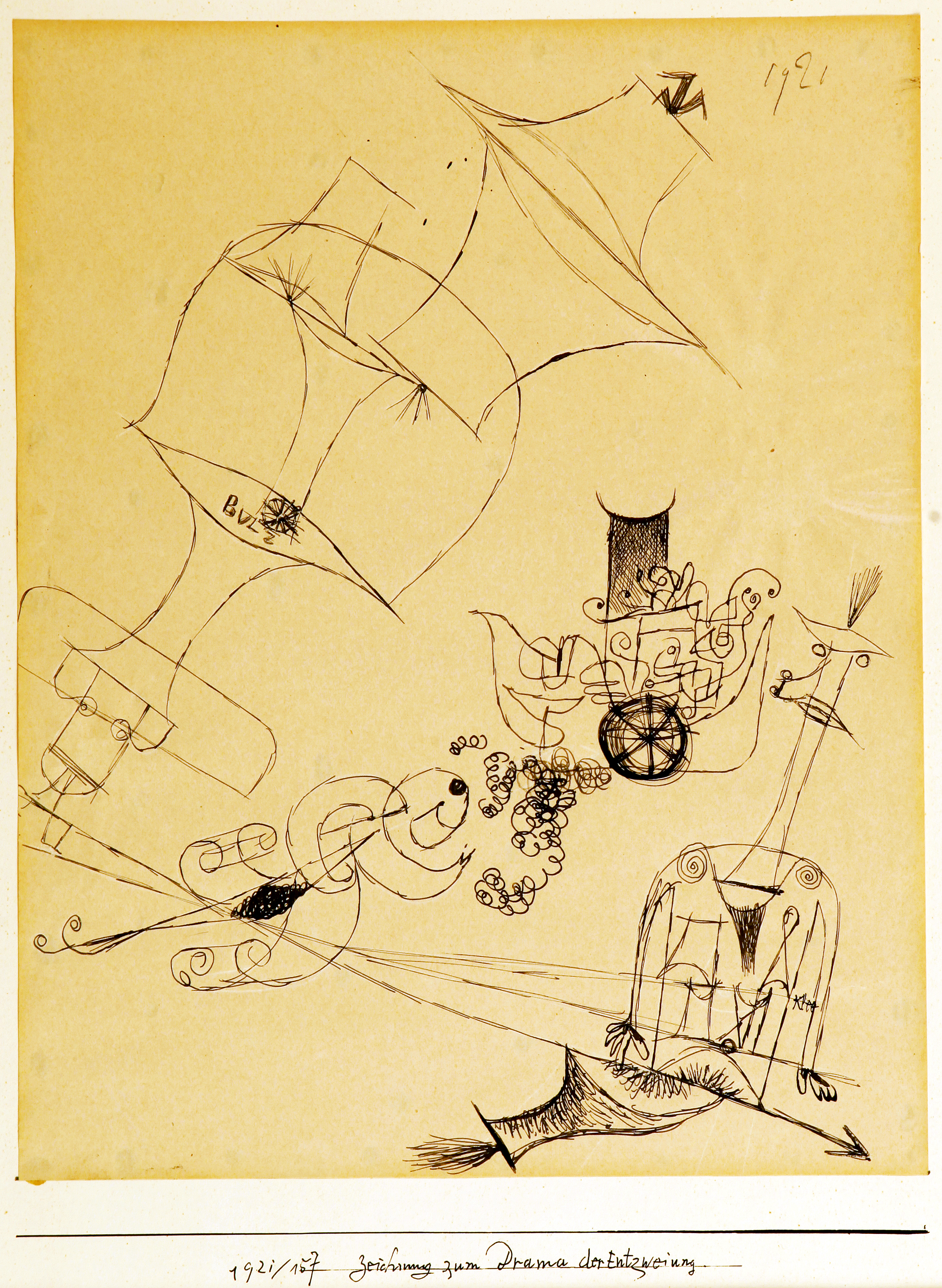

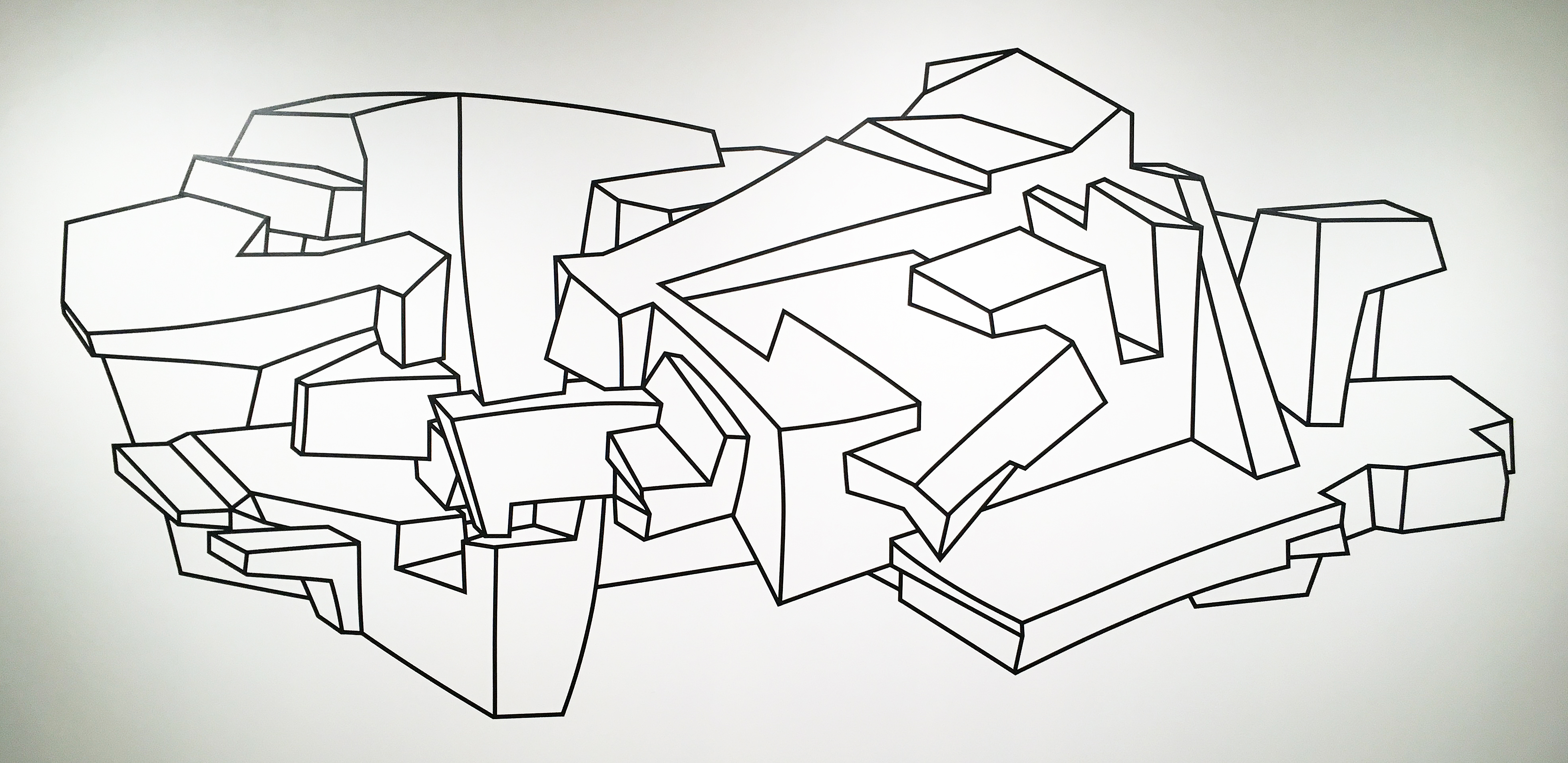

Cody VanderKaay, Bündner Schist, Crepe Tape on gallery wall, 2017

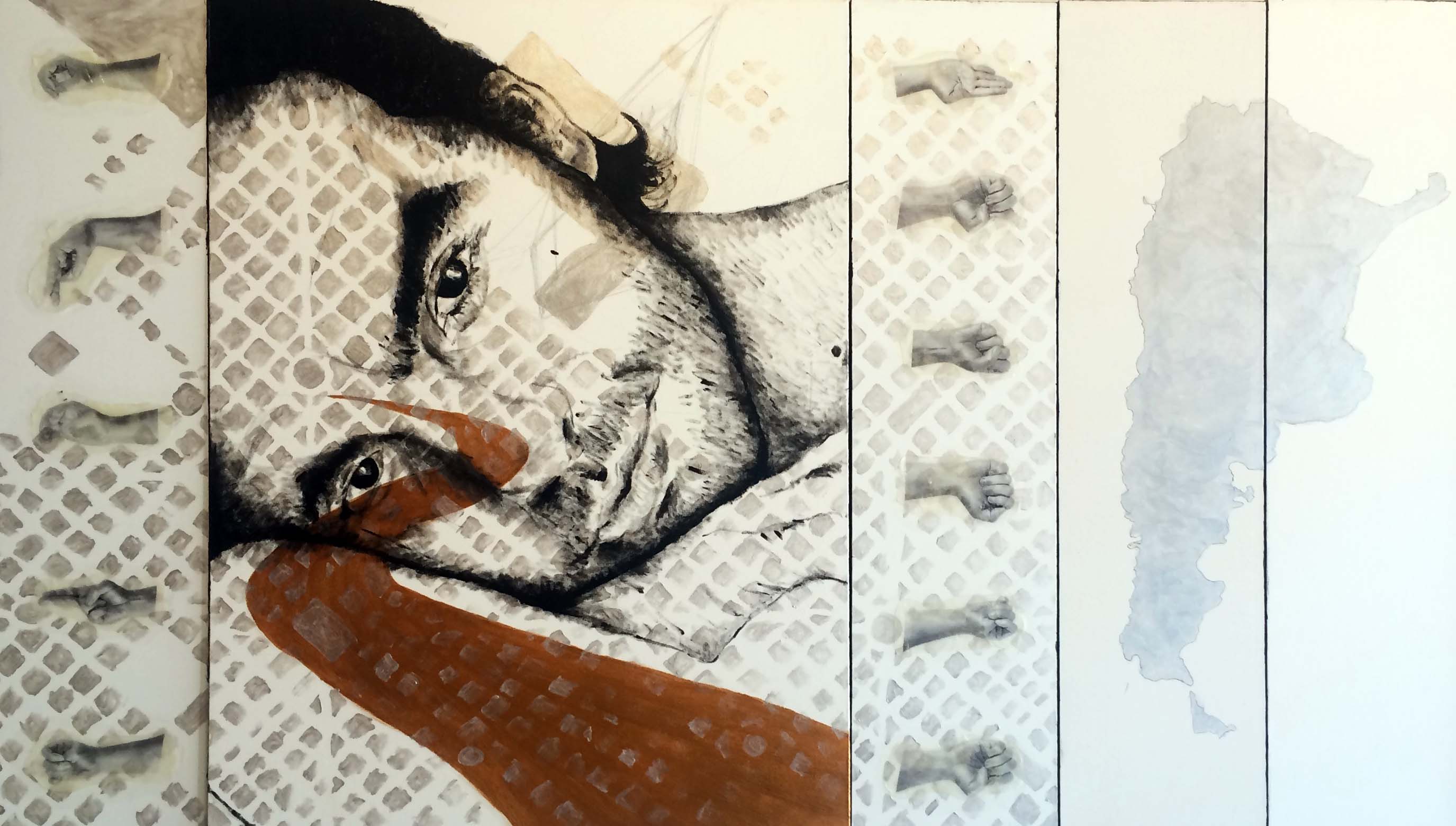

The large black-taped drawing on the gallery wall, Bündner Schist, reinforces elements in the overall exhibition, like a roadmap to his thinking. He builds an amalgamation of trapezoids and variations that make his statement clear and concise, one that offsets the more three-dimensional work that dominates the overall exhibition. As part of the exhibition, we are confronted with the large assemblage of mixed media, Ball Drop, where the artist has presumably collected and large variety of materials and objects that met his fancy, not so different from when an artist collects things they like, placing them on a table (or wall) in the studio. Not quite understanding how this fits into the overall exhibition, I asked VanderKaay to explain this in the last question presented in a short interview.

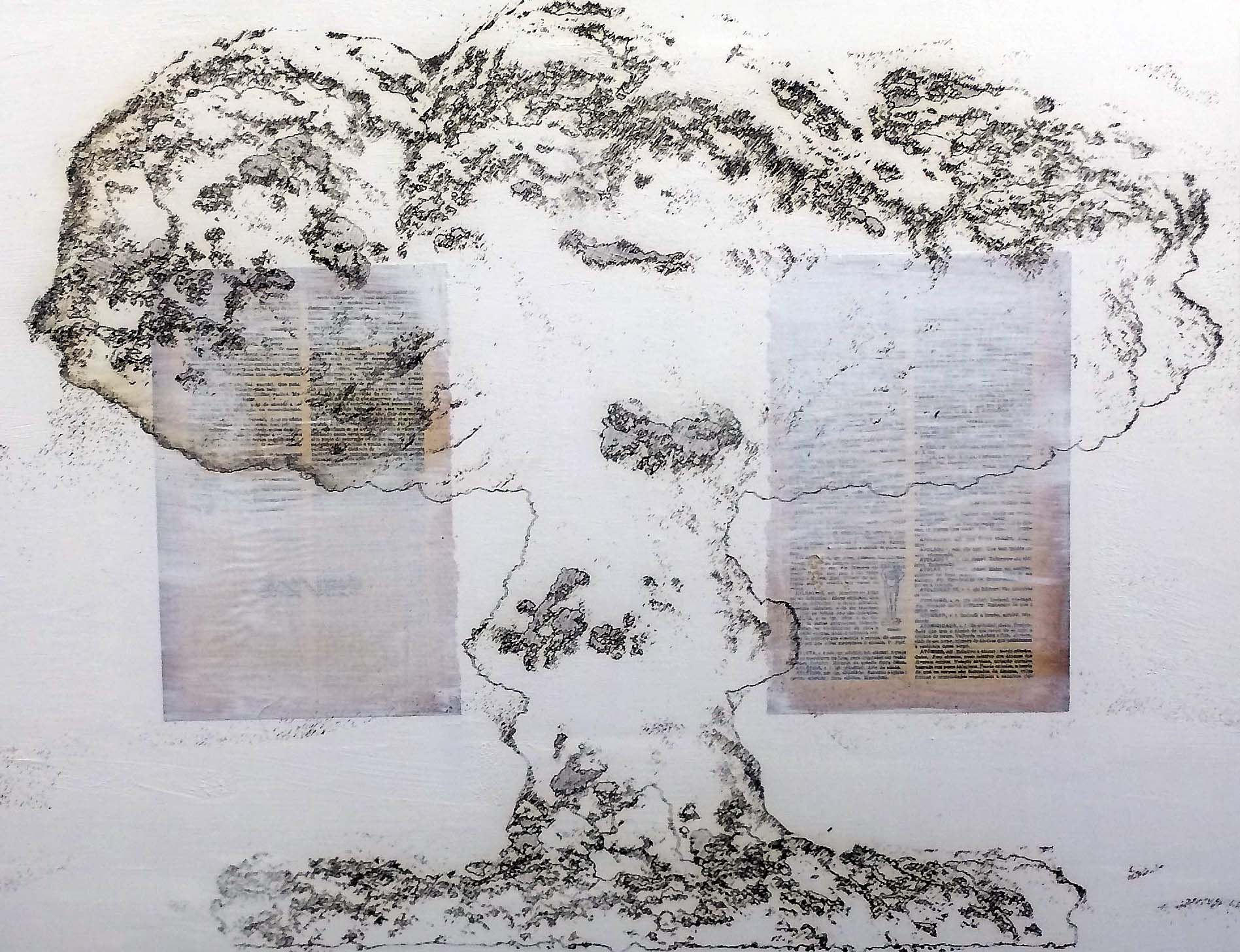

Cory VanderKaay, Ball Drop, 2017

Ron Scott: How and where did you first get interested in visual art?

Cody VanderKaay: I lived in both rural and suburban environments of the Midwestern, Southern, and Western United States. Periodic relocation and travel allowed me to experience a variety of living situations, routines, pastime activities and occupations that inevitably shaped my curiosity. As the son of a residential contractor, I was frequently exposed to architecture, trades labor, carpentry and the graphic art of drafting. As a young man, I trained myself in a number of related skills and techniques, when, eventually my proclivity for making art objects became my principal interest.

I studied sculpture at Northern Michigan University’s School of Art & Design and the University of Georgia Lamar Dodd School of Art, where I received my MFA. After graduating, I relocated to New Orleans to teach visual arts at Loyola University. Today, I am an Associate Professor of Art at Oakland University teaching sculpture, drawing, and fundamental art courses full-time.

RS: How has your worked evolved since college?

CV: The biggest and best change is an ability to identify when my intellect, technical ability and resources are in concert with one another, and encountering that moment again, in the finished artwork.

RS: How is it that you work in such a variety of material?

CV: I’m attracted to the range of qualities and technical constraints that raw materials and objects have; the combinations seem impossible to exhaust.

RS: What artists have most attracted your interest?

CV: Dil Hildebrand, Anne Truitt, Herman de Vries, Ilya Bolotowsky, Norman Dilworth, Tony Feher, and Richard Wentworth

RS: Your work seems to stand alone as single individual pieces. How does the large assemblage on plywood relate to the other work?

CV:The large plywood piece titled Ball Drop wasn’t conceived as an artwork per se, but rather as scaffolding or drawing of sorts. It’s evidence of the forms and subjects I was thinking through in the studio while making the other artworks in the exhibition. The title is a reference to the phrase ‘the penny has dropped’ and points to a realization or discovery that follows a long period of exploration and questioning. Many of the elements comprising the wall are residual, while a few are deeply personal. For example, the small oil painting of the Alps originally belonged to my Grandmother. The painting was given to her by her father when she left the Netherlands for the United States in the 1930’s. I coveted the painting as a child and acquired it after she passed. The wall doesn’t summarize the exhibition, but examining it closely will reveal more about the relationship between the other artworks on display.

RS: Anything else you would like to say?

CV: I find the challenges of working with self-imposed restrictions to be intellectually stimulating and personally significant. A large majority of my artwork is composed of irreducible elements and simplified forms, with surface qualities that raise questions about the substance and physicality of their forms. I often move between disciplines, on two or three projects at a time, and display finished work as a sequence or series of related artworks to bring formal and contextual concerns in closer harmony with one another. I use fabrication, mold making, casting, drawing and collage to produce my sculpture and two-dimensional artwork.

There are artists who focus on a subject for forty years, providing variations in size, color palette, composition and material. Cody VanderKaay is an artist who does not limit his expression to a genre. He is eclectic in his approach to creating his art and, most important, he is curious. Cody VanderKaay is giving an artist’s talk in the OUAG gallery on Thursday, April 6, at NOON.

Cody VanderKaay, Terrestrial Celestial, Open at OUAG – April 9, 2017