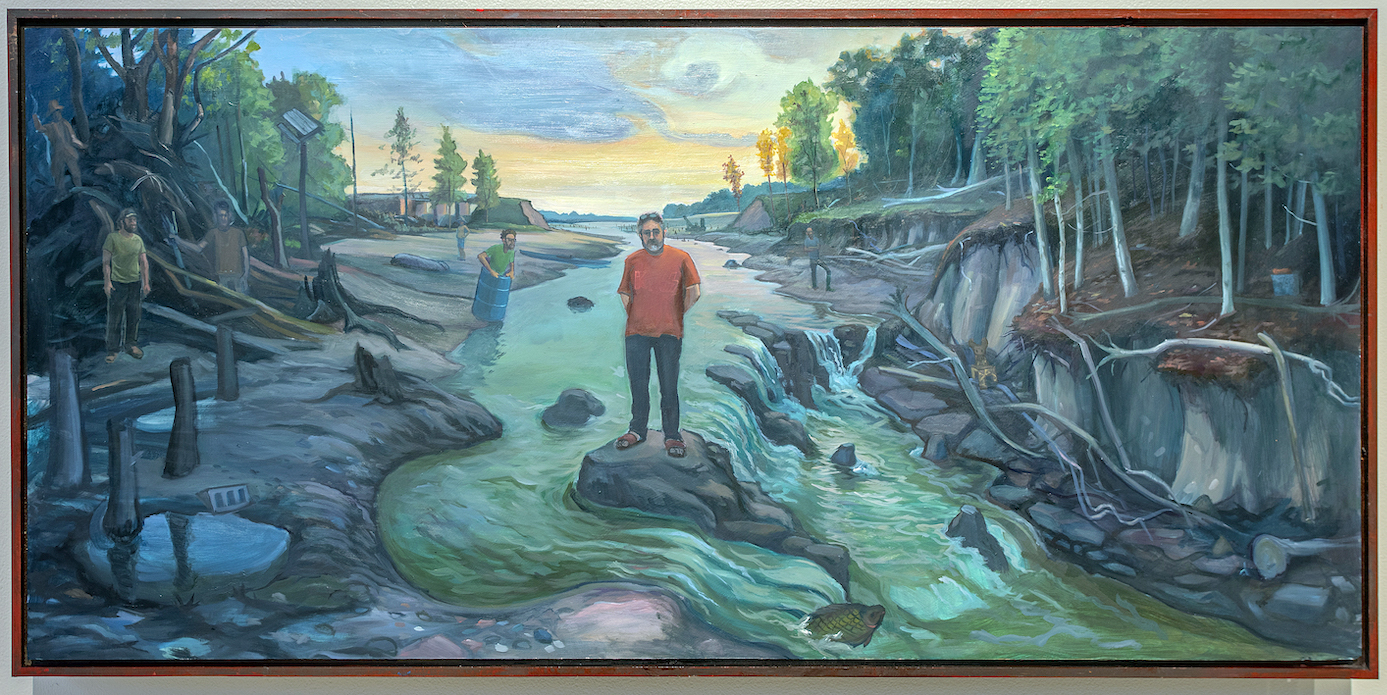

Harold Neal and Detroit African American Artists: 1945 Through the Black Arts Movement at the Elaine L. Jacob Gallery, Wayne State University

Installation view of Harold Neal and Detroit African American Artists: 1945 Through the Black Arts Movement, Image courtesy of DAR

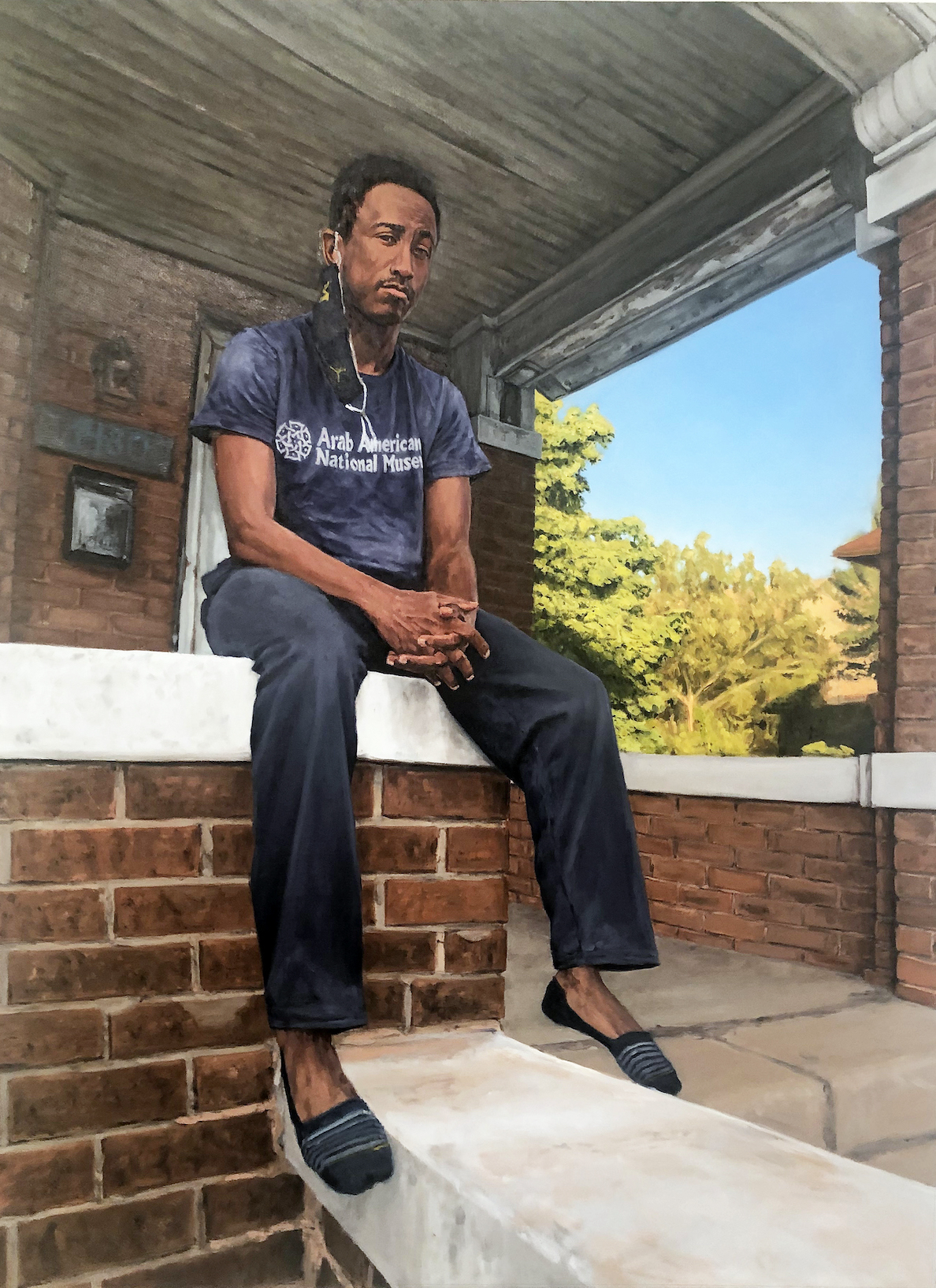

“Harold Neal is a people painter,” so goes the artist’s succinct, self-identifying description of his art, life, and career on the first page of the exhibition catalogue. But this is not a solo exhibition. While Neal deservedly headlines the show, the title adds clarifying information plus a timeline subtitle, finally weighing in as: “Harold Neal and Detroit African American Artists: 1945 Through the Black Arts Movement.” The other artists number ten, and the years actually extend from 1945 – 1980. It is, in fact, an extraordinarily ambitious overview of thirty-five years of African American art in Detroit, and presents both an exhibition and a probing, in depth catalogue, the result of a ten year project, initiated and produced by Julia R. Myers, Professor Emerita of Art History at Eastern Michigan University, who now resides in New Mexico.

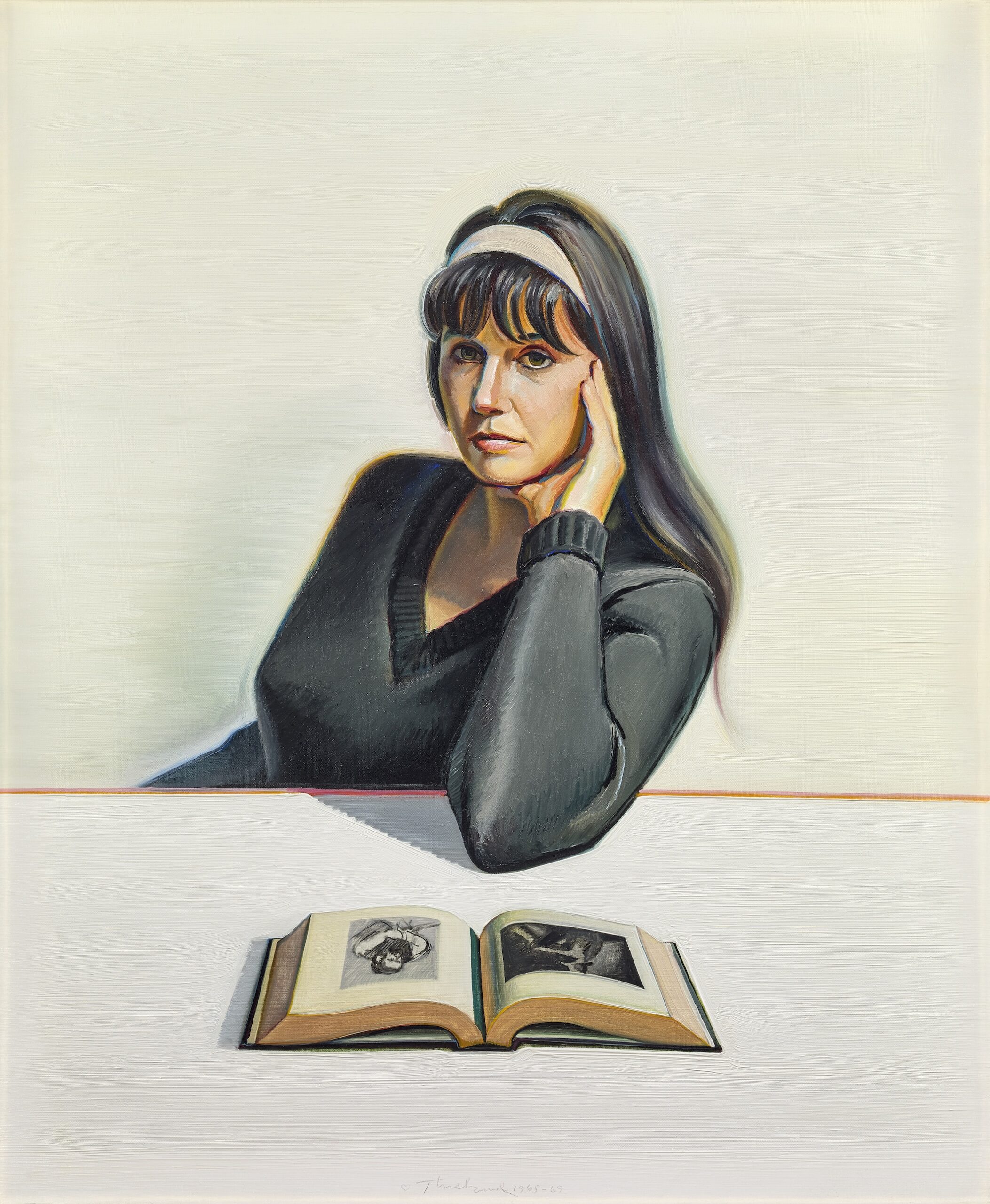

Harold Neal, [Still Life], Oil on board, 12 ¼ x 15 ¾” 1950

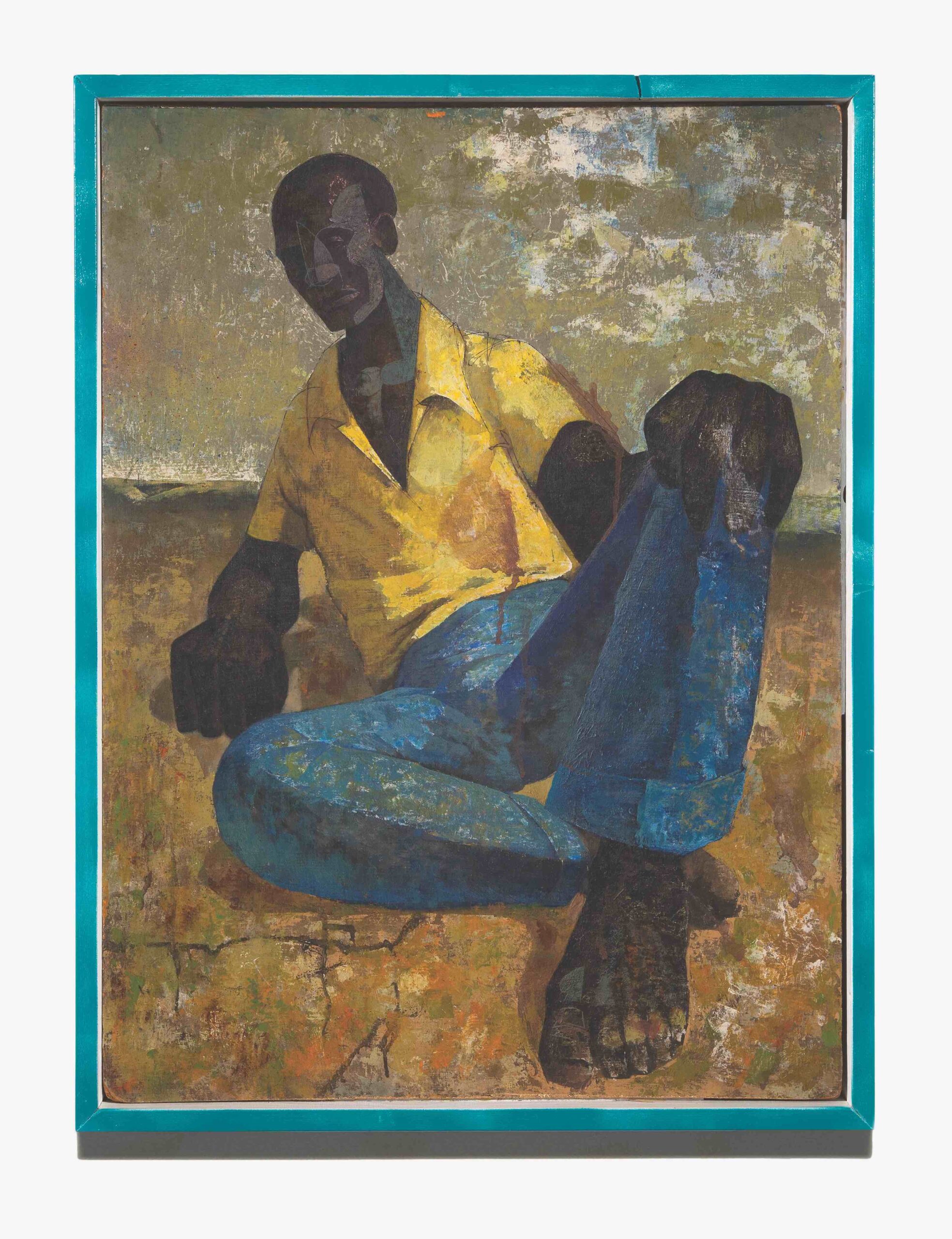

Born in Detroit in 1924 (d. 1996), Neal completed his BFA at College for Creative Studies (1953) at the age of 29 after a decade of on and off enrollment. An early still life of bottles, Still Life, establishes stylistic hallmarks of his oeuvre: translucent layering of thinly pigmented hues, flattened and indeterminate space, and figural representation, a mode influenced by CCS teachers Sarkis Sarkisian and Guy Palazzola. Another early work post-graduation, its Title unknown, portrays a field worker sprawled in the midst of a parched, barren landscape. His striking yellow shirt and blue jeans, foreshortened pose, enlarged hands and feet, and sad expression convey the arid shortcomings of his condition. Notably, his head is farthest from the viewer, emphasizing his deliberate distancing and studied remove from those nearby. Intimations of Rodin’s The Thinker perhaps?

Harold Neal, Title unknown, Oil on board, 32 ½ x 24 ½” before 1958

As the feisty, contentious 1960s dawned in Detroit and across the nation, Neal’s subjects and point of view shifted. The Brown vs. Board of Education civil rights bill had passed in 1954 and Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat in 1955; Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X were promoting their campaigns for social justice for African Americans; the Black Arts Movement(BAM) (1965), Black Power (1966), Black Panthers (1966) and the “Black Madonna” (1967) at Central Congregational Church in Detroit hove into view; while the Detroit revolution of 1967 prompted the 1969 exhibition of Seven Black Artists at the Detroit Artists Market (a first for the Market) and the subsequent founding of Charles McGee’s Gallery Seven (1969-1978) in the same year.

Concurrently, against the turbulent backdrop of the decade, the Black Arts Movement (BAM), founded in 1965, “established” more or less clearcut guidelines that sought to enhance the potency, validity, and accessibility of Black visual art. The directives emphasized imagery that portrayed the experience of African Americans in order to engage Black audiences, and to reject abstract art that dominated the white art world at the time. Or, phrased more colorfully and pertinently, Neal asserted that “Artists must stop being specialists and must be like any other Black man fighting for his freedom [rather than] going along with tired white boys who introduce a series of dots one year and are hailed by critics.” On the other hand, a number of Black artists felt just the opposite, one of whom, Al Loving, queried: “Is art supposed to be propaganda for Civil Rights? That seemed to be the attitude at the time.”

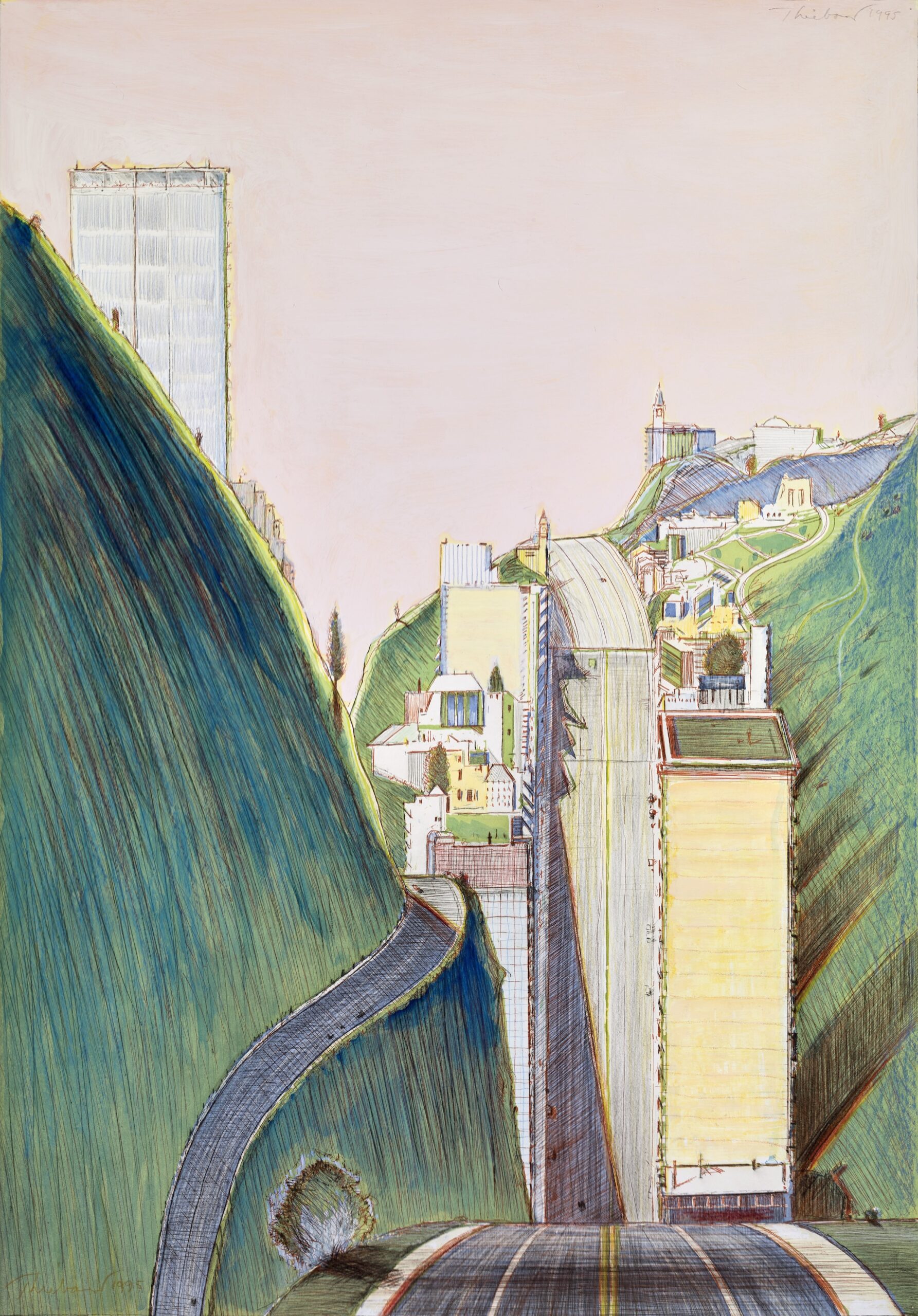

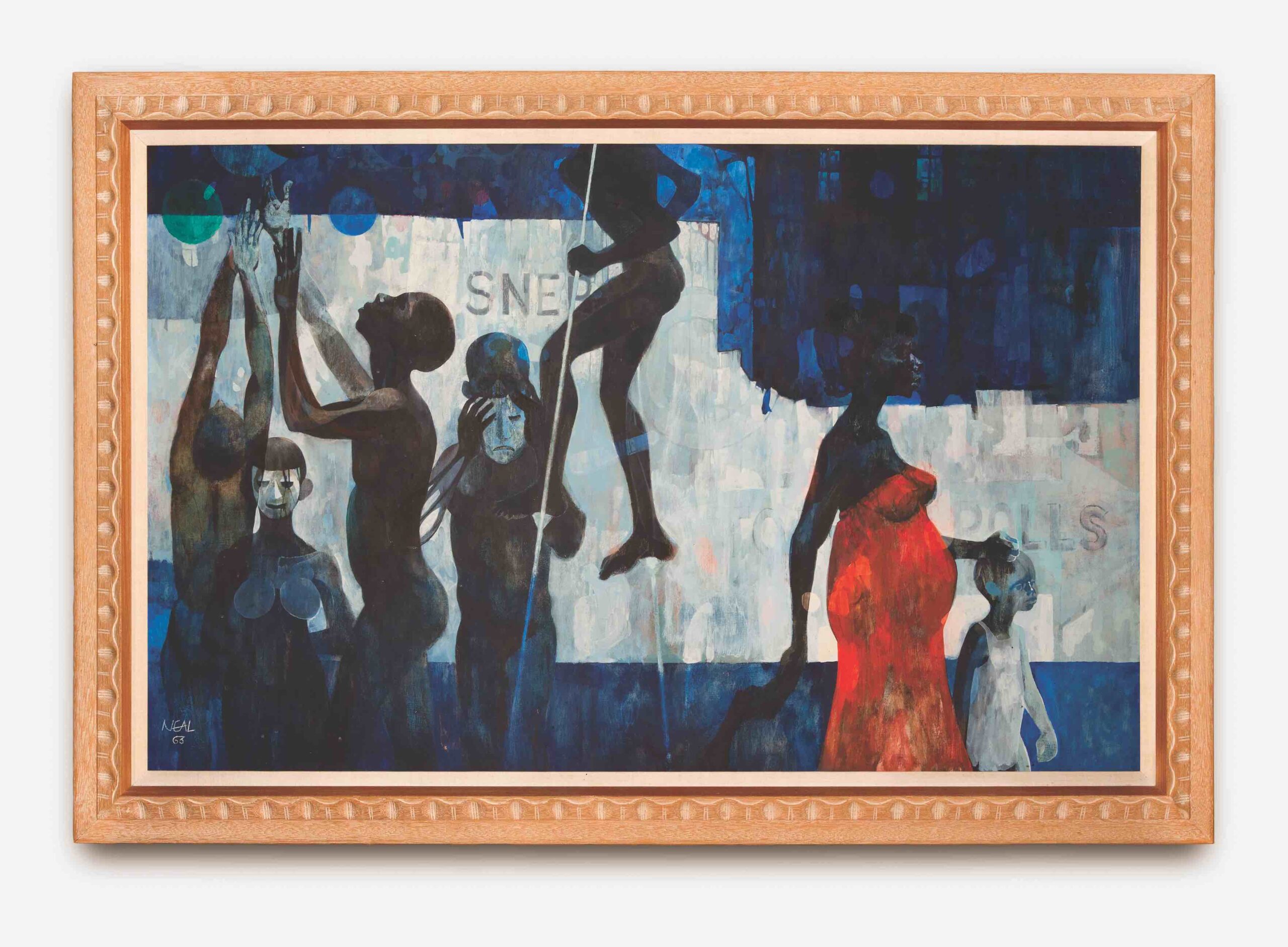

Harold Neal, Status Seekers, Oil on board, 30 ½ x 47 ½” 1963

Resolutely, Neal soldiered on, producing in 1963 Status Seekers, one of the largest and most riveting compositions in the show. It’s a streetscape peopled with two vignettes, a group of adolescents on the left and a pregnant mother and child on the right. Two of the boys stretch upward toward balloons bobbing above them while another status seeker struts along on stilts, his head cut off at the top of the frame. Two others have donned white masks, as they too aspire towards success in the white world. Meanwhile, the woman in red strolls by defiantly ignoring the foolish boys from whose bogus goals she seeks to shield her young child.

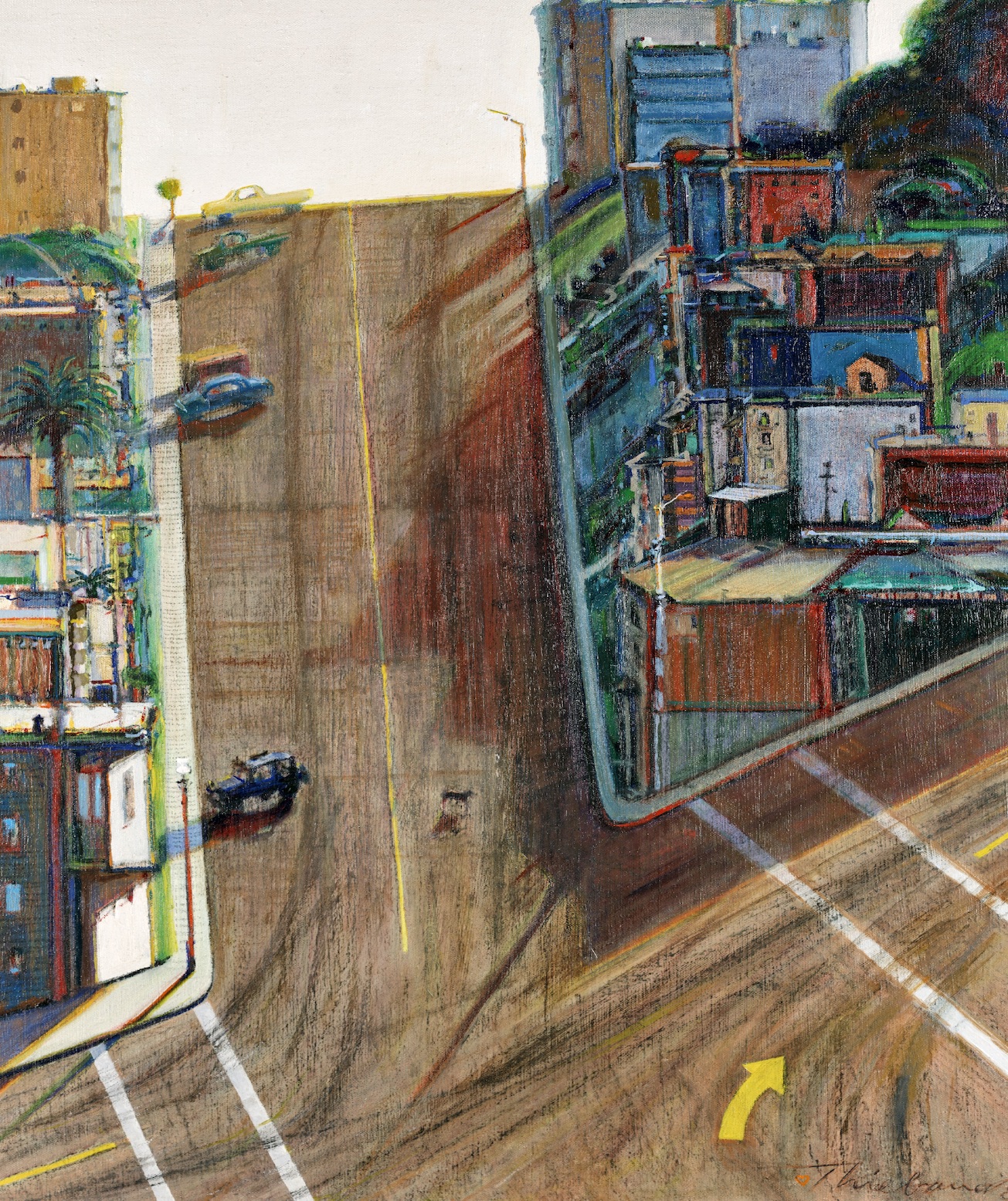

Harold Neal, Man Span, Oil on board, 23 ½ x 47 ½” 1963

Another stunning and rather unexpected image from the same year, 1963, Man Span, represents a bridge raised high above the chasm it fords. Its tall, elegant red/orange columns support a roadway absent any sign of vehicular traffic. As Neal explained, laborers who built the structure are whom Man Span” celebrates: “Sometimes in seeking respite [from anger about the treatment of African Americans] I try to show through the paining of bridges, houses, and still life what the human hand is capable of in the brief period between its destructive endeavors.”

Harold Neal, Title unknown Oil or acrylic on board, 37 x 30” 1968

A disheartening but compassionate trio of images from the late 60s continue to broach the inequities of racial strife, beginning with Title unknown, Neal’s stoical portrait of a semi-shadowed woman displaying in her arms for all to see her dead, bloodied child slain by a National Guardsman during the Detroit rebellion of 1967. The mother and child, centralized in the composition, are redolent of both a classical madonna and child or Pieta composition. The date of the child’s death, 7-25, is incorporated into the light filled, graffitied urban setting that Neal often employs to contextualize his dramas.

Harold Neal, Title unknown, Riot Series?, Oil on board, 24 x 39” 1960s

In another Title unknown work, Neal advances his subjects so close to the surface that upper and lower parts of their figures are cut off by the picture frame, so observers all but merge with the pictorial space of the image. Here, a seated mother and child on the left are paired with a male figure on the right, his back turned to the spectator and his hands tied. Suspended in time and place, they wait for the inevitable. The savory pink, lavender, and red hues of their attire, plus a gray, overcast atmosphere, adds poignancy to the taut, anything-could-happen deadlock which fences them in and ties their hands.

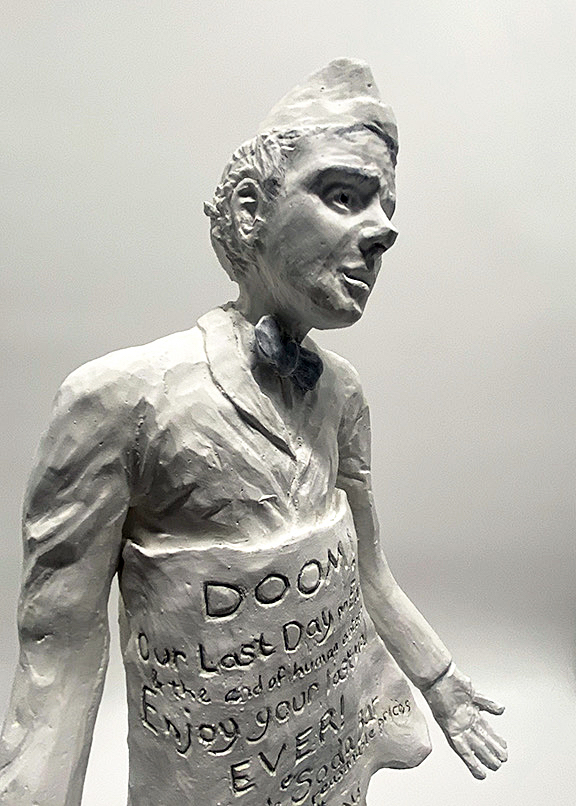

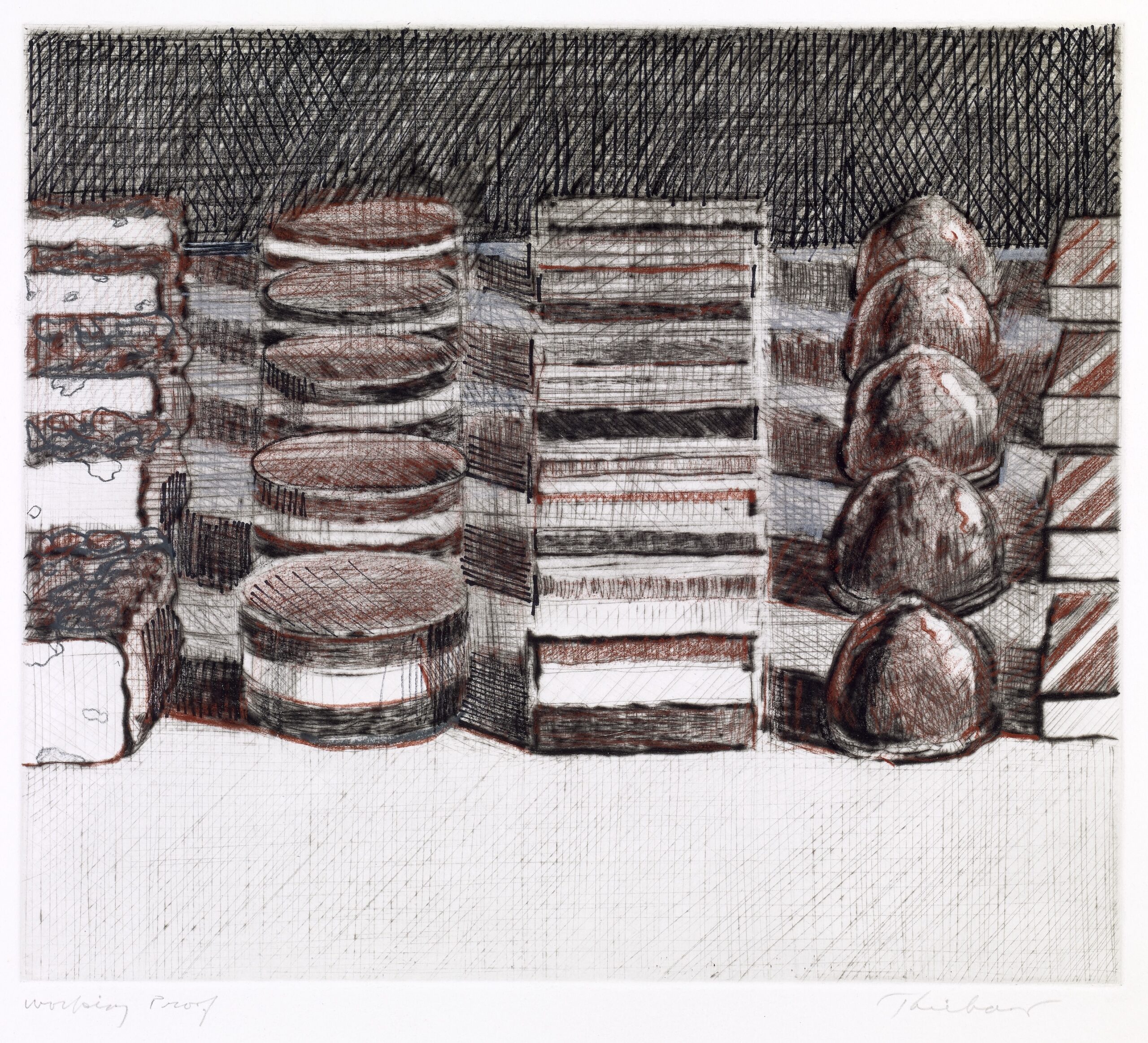

Harold Neal, Rag Doll, Lamp black on paper, 28 x 47” c. 1967-1969

The third of these late 60s depictions is the most searing of the lot. Titled Rag Doll, it is chromatically limited to black and white and to a single figure, but is sizable in scale (28 x 47”) for maximum impact. Viewers witness an incensed Black boy who, with his bare hands, deliberately and furiously rips and tears apart a white rag doll, peeling off its arm and severing its torso. Kinship with Goya’s visceral “Disasters of War” echos here. Exhibited in the 1969 Seven Black Artists exhibit at the Detroit Artists Market, a breakthrough show curated by Charles McGee, its present day aura registers as fiercely and as hauntingly now as then.

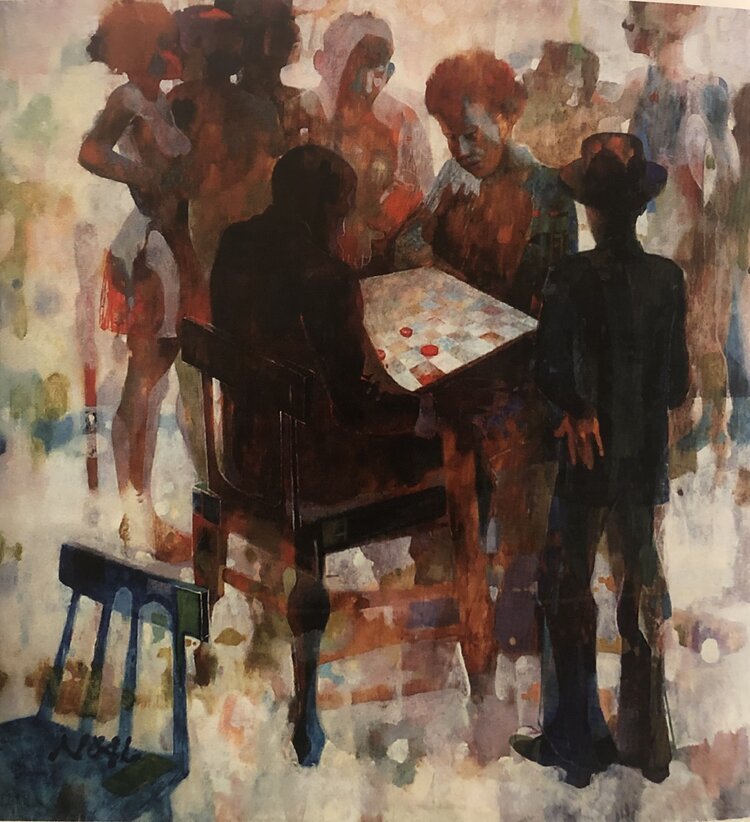

Harold Neal, Checkers, Oil on board, 51 x 48” c. 1972-1973

By the mid to late 70s, Neal, along with many of his BAM cohorts, had ”cooled his fire”: “I don’t have time to be angry anymore….I can’t carry the burdens of oppression on my shoulders my whole life.” Checkers, from 1972-73, is suffused with light and transparency as onlookers and players mingle and merge around a floating checkerboard, one of the last of Neal’s paintings to appear in the show. Among subjects that continued to appeal to him were jazz and blues, which he referred to as “African American Classical Music.” Participation in outreach social programs, conferences, art councils, and teaching for many years at Wayne County Community College also provided an outlet for his socially progressive urgings: “I have awakened a lot of young people to their potential and I encouraged them to pursue alternative means of expression.”

A video interview from 1971 embedded in the show introduces visitors to Neal’s calm, composed demeanor even when asserting controversial and passionately felt points of view. He argues, for instance, that abstract artists “immunize” themselves in their studios, selfishly thinking they own their talent and style without acknowledging the societal responsibility for human intercourse. He asserts as well that the 60s expression, “Black is Beautiful,” is of manifestly lesser social and political importance than “Black is powerless, Black is hungry, Black is jobless, and etc.”

Lastly, writing in 1974, critic Charlotte Robinson observed that Black “social statement is almost never hanging on the walls [of] large art institutes or museums and rarely even in white galleries.” Well, in fact, here it hangs, on the walls of the Jacob Gallery at Wayne State University in Detroit for two more months. Do plan a visit.

Harold Neal and Detroit African American Artists remains on view through – Jan. 20, 2022, at the WSU Elaine L. Jacob Gallery. Contact the gallery in advance at tpyrzewski@wayne.edu to schedule your visit.