Asymmetry, installation at Library Street Collective All images: Library Street Collective

Asymmetry, a two-person exhibition of work by Robert Moreland and Jacqueline Surdell on view at Library Street Collective until May 4, 2022, continues the gallery’s program of pairing the work of two artists in a provocative dialog. Zenax, the recent show of Beverly Fishman and California painter Gary Lang could have been described as a more-or-less harmonious conversation; Asymmetry is something more along the lines of a very civil argument.

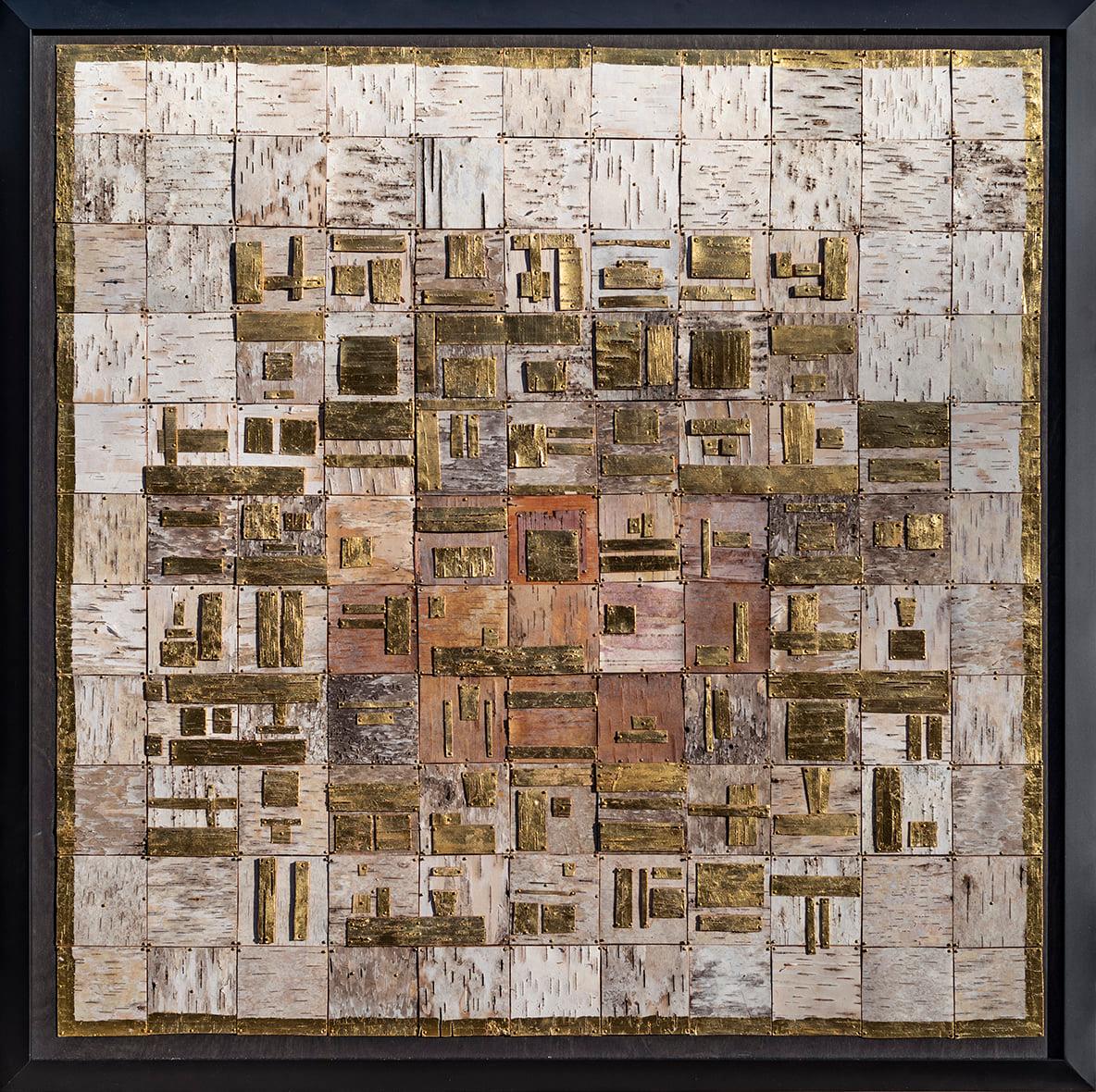

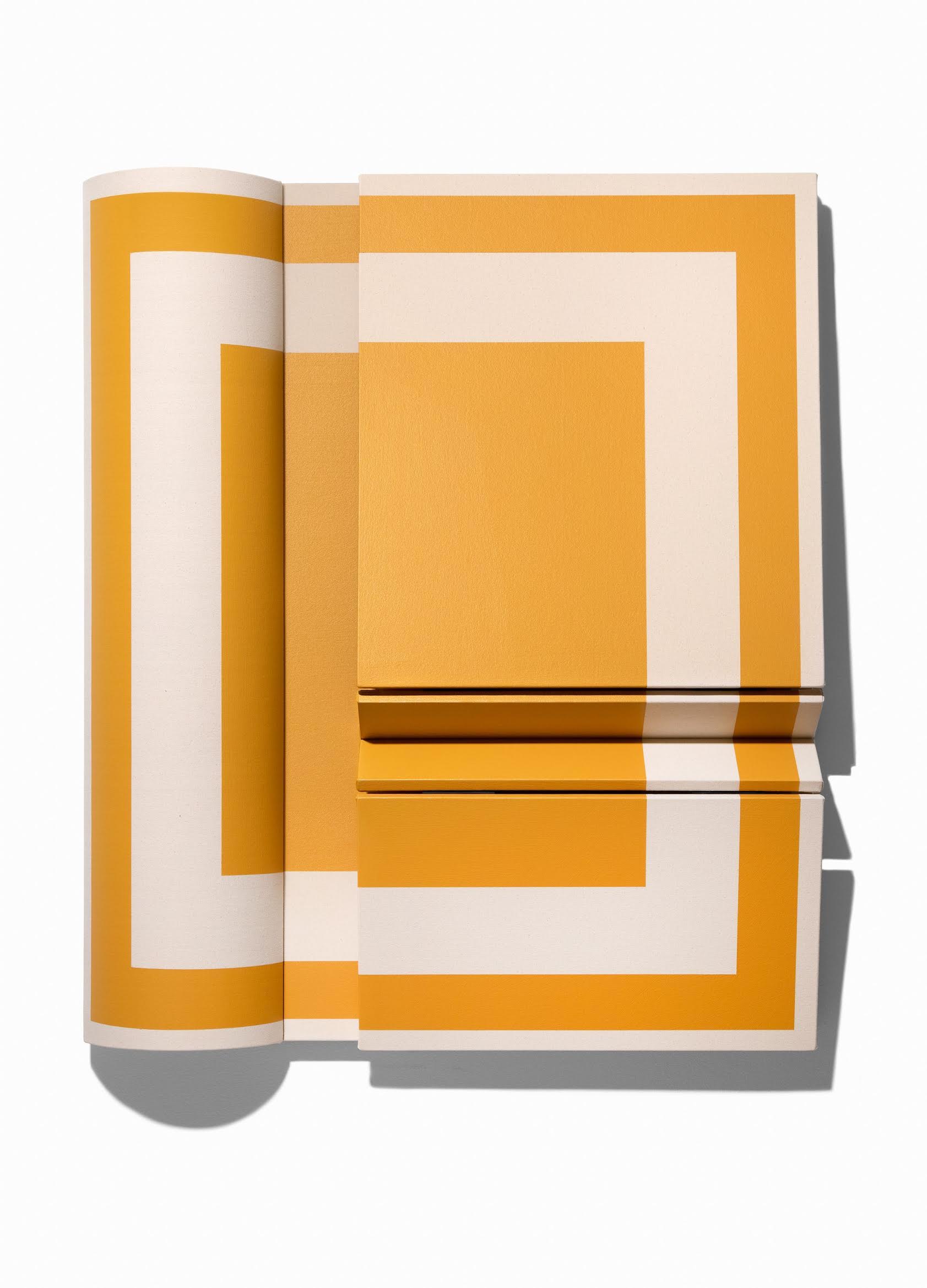

Untitled Yellow Square, by Robert Moreland, 2022, canvas on wooden panel with acrylic paint, tacks and leather hinges.

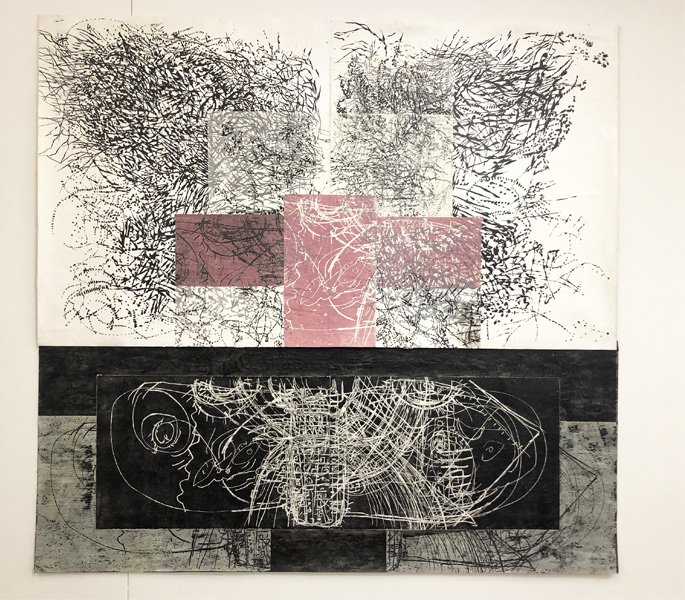

The exhibition demonstrates that the tenets of Constructivism–that materials and methods of construction generate the meaning and physical presence of art objects–retain their relevance well into the 21st century. This philosophical habit of mind underpins the work of both Moreland and Surdell, but as one might expect of a line of aesthetic thought that is over 100 years old, their common starting point has diverged, resulting in endpoints that are quite far from each other in appearance and intent.

Born and raised in Baton Rouge, Robert Moreland dropped out of high school in his sophomore year and later began to teach himself about art by hanging out with friends at the margins of art school, talking to the professors and attending the occasional lecture. He worked with a woodworker for a time, where he learned the craftsmanship that is still a salient feature of his art practice. Moreland moved to L.A. some years ago and credits the anonymity and openness of the city as a creative catalyst for his recent work.

Moreland prizes the labor of making art as a meditative act, and gravitates to the routine, everyday nature of fabrication. The artist proceeds with deliberation when creating a piece, a working habit which he credits to his art conservator mother who, he says, showed him how to “slow down and take my time.” The artist uses hundreds of tacks—invisible on the face of the constructs–to secure the cloth on the underlying wooden components. Leather hinges connect the constituent pieces of each artwork. Taken together, these components and physical processes define his highly personal, almost ritualistic art practice.

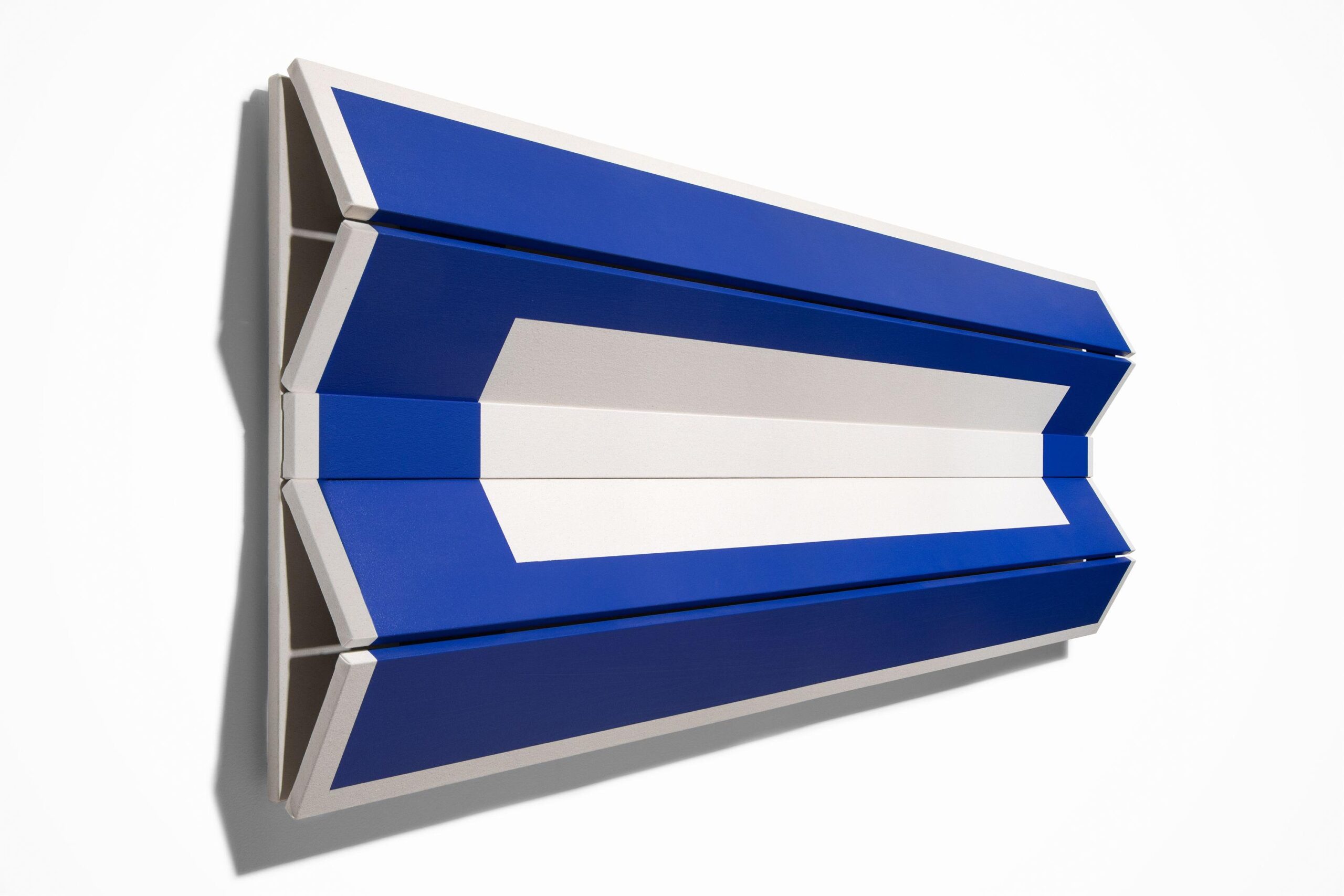

Untitled Blue Rectangle IV, by Robert Moreland, 2021, canvas on wooden panel with acrylic paint, tacks and leather hinges.

Untitled Blue Rectangle IV, by Robert Moreland, 2021, side installation view.

The artist describes himself as more of a builder than a painter. These paintings or sculptures (Moreland resists referring to them as one or the other) operate as activators of the space around and in front of them. His artworks in Asymmetry, each listed as “Untitled” beside an austere description of their physical shape and color, are painted with stripes or squares of an intense single hue that follows the contours of each piece. The canvas components are stretched over rigid rectilinear –and occasionally columnar–wooden structures, which are then assembled into folded and buckled shapes that call to mind the vintage toy Jacob’s ladder, or perhaps reference industrial shapes like tank treads or conveyor belts. The 5 precisely constructed pieces installed in the gallery look as if they could fold or open or climb down the wall, implying movement event though they are static.

More defined by what they do not offer rather than by what they do, Moreland’s constructions are rigorous and demanding, their expressive content confined within narrow formal boundaries that refuse referentiality, gesture and imagery. In this, he follows in the footsteps of a well-established philosophy of aesthetics practiced by mid-century minimalists like Ellsworth Kelly and Donald Judd, artists Moreland professes to admire.

Not one but not two either (blue), by Jacqueline Surdell, 2022, braided cotton cord, steel, 108” x 51” x 11.” Photo: Library Street Collective.

In emotional temperature and methodological expressiveness, the work of Jacqueline Surdell could hardly offer a stronger contrast to Moreland’s recessive artworks. Exuberant and improvisational, her three free-form tapestries made from thick ropes and lines nearly dance off the wall. They nod to the warp and weft of traditional fiber works, but with these hefty woven pieces, Surdell has achieved a kind of painterly freedom in execution that is both novel and exhilarating. In overall shape she allows some scope to the effect of gravity, with elements of the artworks seeming to sink downward, referencing natural forms like bird nests or insect cases. Clotted knots and twisty braids surround circular portals, while individual cords escape and crawl across the floor.

As a native Chicagoan, Surdell feels related to the environment, history, and blue-collar work ethic of the city, with childhood memories of her grandmother’s plein air landscape painting adding yet another level of complexity. The physical act of creating the works, which weigh an average of 150 pounds, demands considerable physical strength that the artist, a self-described recovering athlete, has in abundance. She often uses her own body as a shuttle, weaving pounds of rope together as she unifies figure and ground.

Earth Licker, by Jacqueline Surdell, 2022, Braided cotton cord, nylon cord, steel, 120” x 120” x 16.” Photo: Library Street Collective

Not one but not two either (blue-detail)

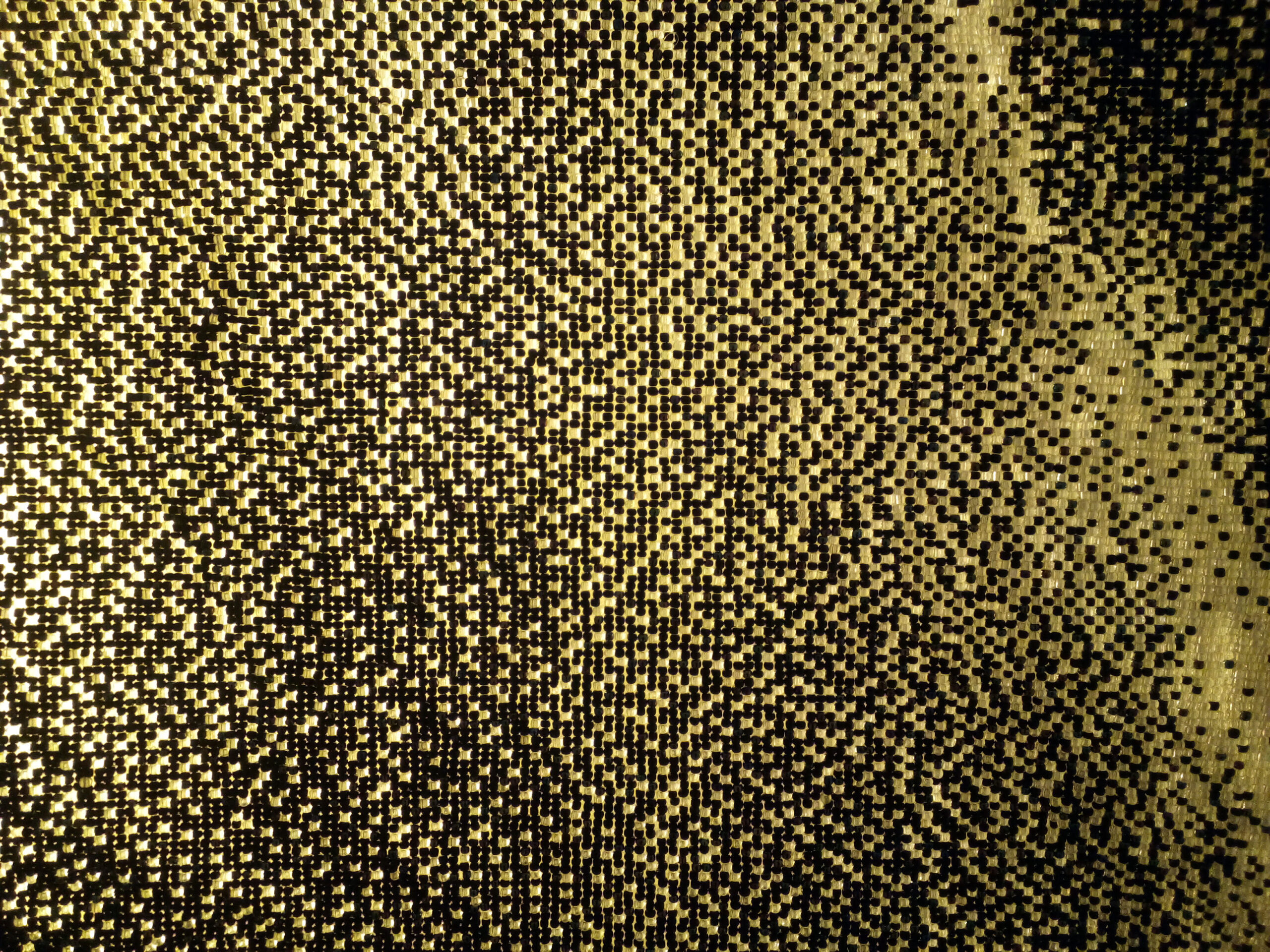

The palette of Surdell’s work is determined by the native color of commercially available nylon and cotton lines. The repetitive, almost beaded effect of row upon row of knots in Earth Licker suggests a ceremonial process like the traditional craft of some imaginary future tribe. The woven elements frame and celebrate the implied portal. In the other two pieces, Not one but not two either (blue) and Not one but not two either (red), triangular imagery points to the open spaces, setting up a bilateral conversation between a circular void and pointing chevron. Her process is open-ended and spontaneous, yet the results seem inevitable.

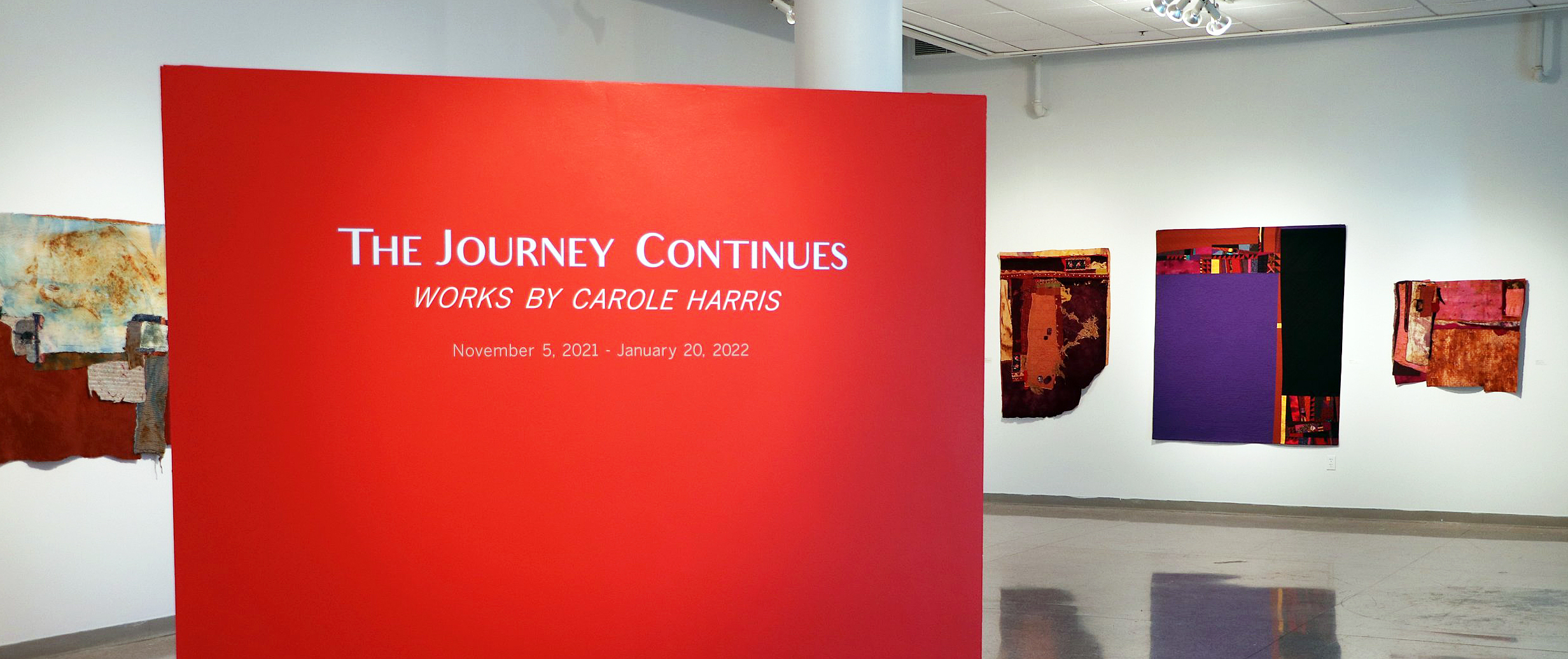

Fiber art, a medium long devalued because of its association with women’s work, seems–at last–to be coming into prominence as a medium. Here in Detroit, recent shows of woven work by distinguished international textile artist Olga de Amaral at the Cranbrook Art Museum, as well as exhibitions by Detroit artists Carole Harris, Boisali Biswas and Jeanne Bieri, seem to indicate that fiber art has entered a new era of acceptance as a major medium of expression. Surdell’s work is a welcome addition to this burgeoning contemporary art practice.

In this age of pluralism and inclusivity, these contrasting bodies of work by Robert Moreland and Jacqueline Surdell in Asymmetry represent two valid ways of making and thinking about art among many. Moreland’s artworks depend upon an established minimalist esthetic that retains considerable currency in contemporary art, even as Surdell’s tapestries set off for unknown territory. The choice is not either/or, but both/and.

Asymmetry, a two-person exhibition of work by Robert Moreland and Jacqueline Surdell on view at Library Street Collective until May 4, 2022