Ryan Standfest: THIS MUST NOT BE THE PLACE YOU THOUGHT IT WOULD BE at the Wayne State University Art Department Gallery

Installation view with view of “Factory Heads” All Photo images by PD Rearick

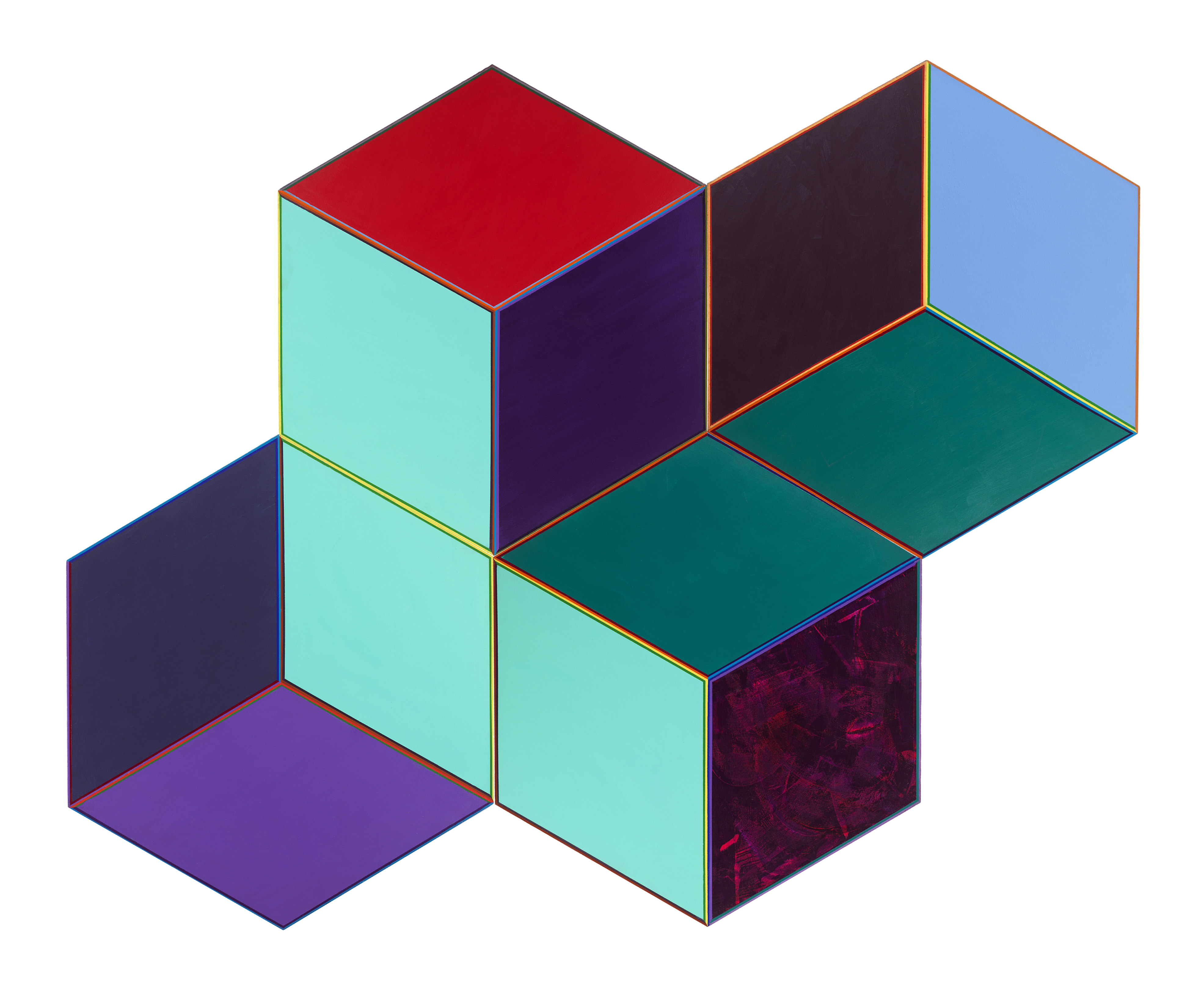

Aside from the subversively compelling and diverse mix of genres and styles of his art making, the dominant feature of Ryan Standfest’s exhibition is his irreverent, comic graphic sensibility. Whether in dark comic video, social and political satire comic, joke books, painterly advertisements, agitprop theater, or comix strips, everything is subject to its scrutiny. In one of his remarkable “writings” found on his website he narrates the story of his boyhood adventure in a church parsonage storage shed, where he’d wandered, existential 9-year-old boy style, to experience an epiphany of the aesthetic value of comic books. There in the dark shed, in his prepubescent glory, sitting upon a stack of 15 years’ worth of discarded Detroit Free Press newspapers, dating back to 1968, he discovered and proceeded to search for, cut out and scrapbook, the “Dick Tracy” comic strips. The narrative itself is an arch-comic book style self-discovery! Most importantly it is where Standfest began to savor the essence of pulp paper culture and revel in its wanton working class virtues as well as create a method for art making. The rest is his story.

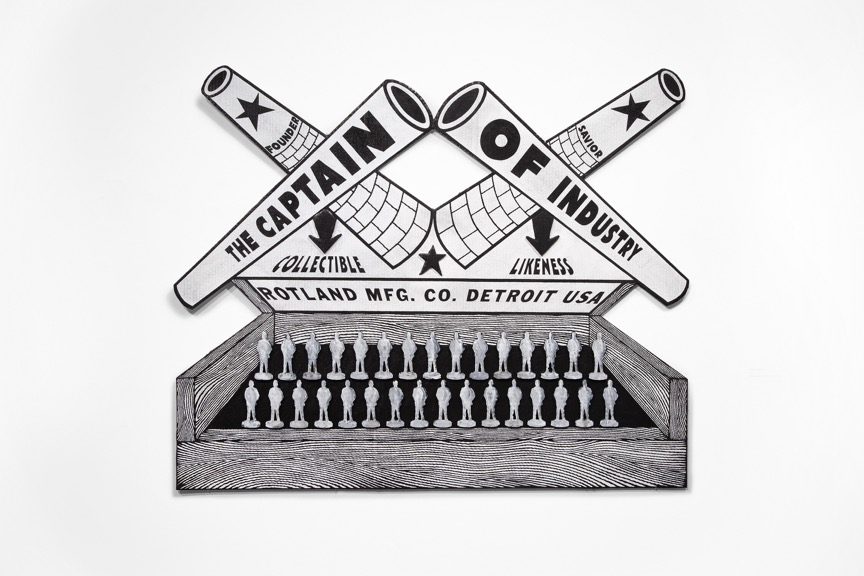

Ryan Standfest, “The Captain of Industry,” gesso, graphite, ink, enamel on cardboard, 34 ¾” x 42 ¼”,2018

The title of the Standfest’s exhibit at the Wayne State University Art Department Gallery “THIS MUST NOT BE THE PLACE YOU THOUGHT IT WOULD BE,” is typical ominous and foreboding language that you might find in a comic strip. Both physical and psychic displacement are the basic tropes of comic strips. In the small, but explosive, little boxes filled with minimal little drawings of “the comic section,” all sorts of mishaps, mysteries, surprises and aporia occur and– whether its Dick Tracy, Beetle Bailey, or Pogo—the comic strip world turns on the displacement of logic and the predictable; expecting Utopia and disappointingly ending in Dystopic visual gag of some kind. Standfest is all about language and his title here has it all: past tense, present tense, future tense; ironic surprise. Part of the issue of looking at his work is precisely unraveling the ball of time and space it encompasses. The exhibition itself proceeds a bit like a comic strip, going from inscrutable painting to painting, with only the barest of word play, letting the audience figure it out for themselves.

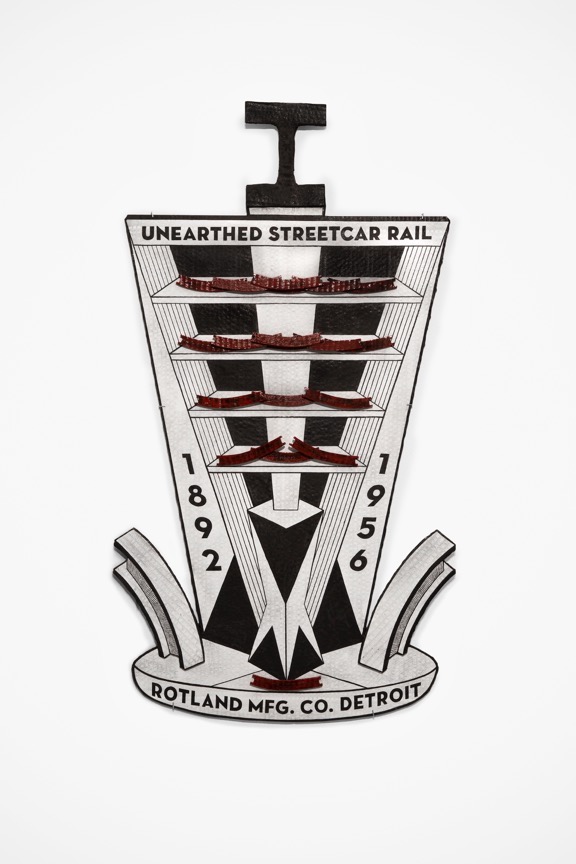

Standfest’s overall oeuvre is then one of bewildering sense of time and space, of nostalgia for promised future and the agony of a defeated utopia. His prime invention in this exhibition are the cardboard panels that seem to be 2-D “point-of-purchase” display cases of Standfest’s “Rotland MFG. Co., Detroit, Mi.,” and function almost as heraldic banners that parody the language of advertisements where things are either promised, promoting a bright future, or liquidated, suggesting collapse. They suggest a time after World War l, when “Developers” were building Detroit and offering a utopian future for everyone. Standfest’s “The Captains of Industry” painting is an ironic image composed of crisscrossed smoke stacks and canons (the mix of war and industrial culture can’t be missed) and filled with little token statuettes of, probably, Henry Ford, like the Catholic Dashboard statues of Jesus and Mary that people used to put on their car dashboards to protect them from evil. (There must have been a spiritual side to Ford.) There’s thirteen heraldic-like paintings and each, like heraldic coats of arm crests, celebrate moments (victories or defeats) of social and economic organization. “Unearthed Streetcar Rail” celebrates an ironic discovery of an already existing railroad system, made by workers when excavating Woodward Avenue for the new Q-Line and serves as reminder of the redundancy of Detroit’s city planning. His painting “Vintage Union Handbooks,” ironically promotes the hand book as memorabilia of an institution (labor unions) that saved workers from abject abuse. Libraries, decommissioned schools and factories, dream houses, cheap land are all victims or promises of utopia.

Ryan Standfest, “Welcome to Fordlandia,” Gesso, charcoal, enamel, and varnish on cardboard, 49 ½ x 31”, 2018

Complementing “The Captains of Industry” painting is Henry Ford’s experimental factory town in Brazil, Fordlandia, “celebrated” by a derelict looking banner painting suggesting the failure of Ford’s colonizing enterprise to build a Michigan style rubber factory in the Amazon jungle.

All of the banner paintings employ the graphic style of early 20thcentury Futurists and Russian constructivists, with their explosive, geometrical angularity, always suggesting machines and speed, such as the Italian and Russian designers Fortunato Depero and Gustav Klutsis; a mix of Industrial Capitalism and Bolshevik revolution, perhaps implying they were both failures. The image on the eroding Fordlandia banner seems to be a throne for Henry, the king of industry, himself.

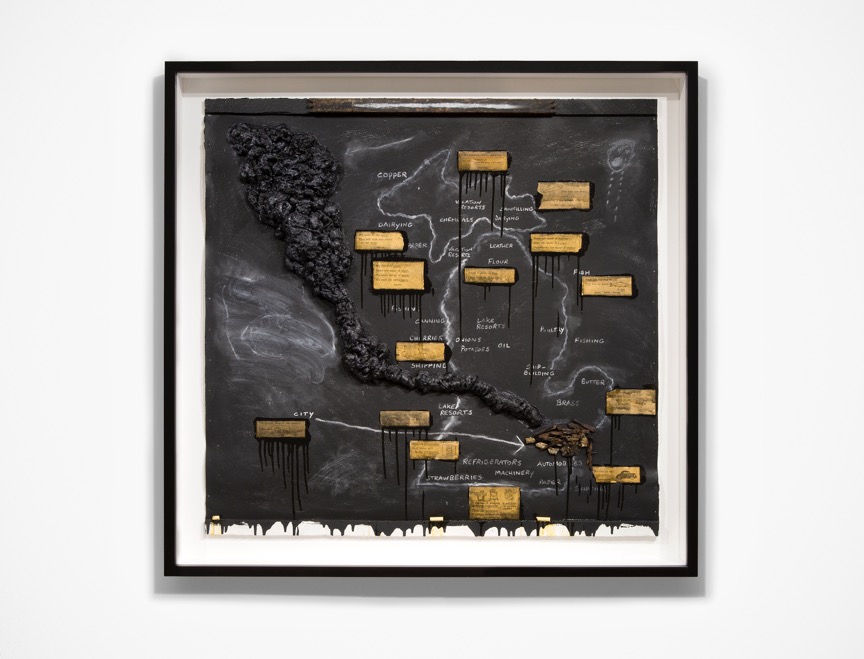

There’s a host of Standfest’s heraldic-like paintings and images to unpack and sort through and they accumulate into a mapping of Detroit and Michigan’s industrial production and the havoc it rained on the city. There’s even a black painting of the outline of the mitten of the state of Michigan belching out a plume of oily smoke from Detroit, its catastrophic epicenter, and featuring locations of all of the products, from cars to copper, of the state.

Ryan Standfest, “A Child’s Picture Map,” gesso, acrylic, wood, oil, chalk, collage and mixed media on Arches, 47 ½ “x 47,” 2018

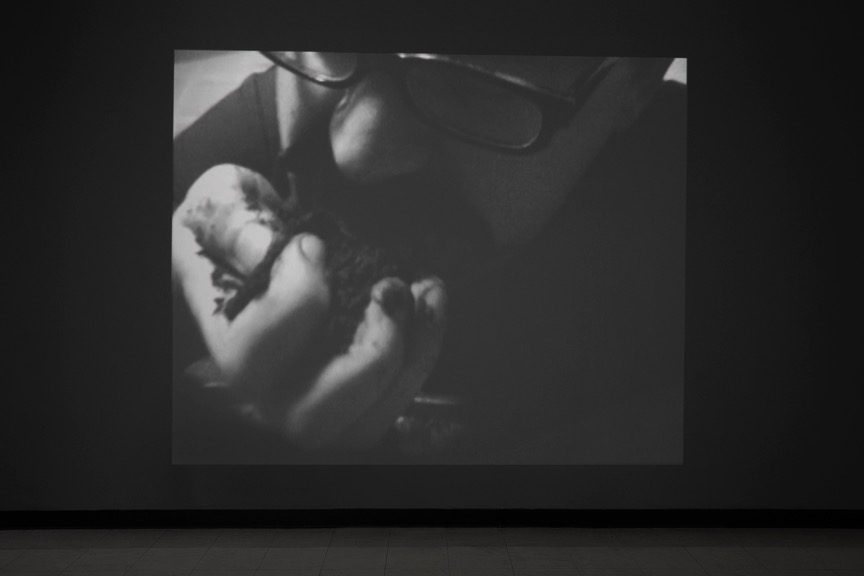

Standfest’s black humor, about which he writes on his website, is employed in a B&W digital video, “THE DIRT EATER,” which sees a broken Chaplinesqe character, Mister Ricky, played by himself, sitting down in a gloomy basement at a T.V. tray to eat a plate of dirt. Photos of Gramps, who was laid low by alcohol and tobacco, punctuate Mr. Ricky’s dinner of dirt, meanwhile Grammy sits by the old radio upstairs listening to Irving Berlin’s chestnut, “I Want to Go Back to Michigan,” a song about nostalgia for farm life in Michigan. The dirt that Mister Ricky eats is from Gramp’s garden behind the garage. While “The Dirt Eater” is a painfully humorous satire on the working-class nostalgia, it is a not a misrepresentation and is realistic in its portrayal of the dark, melancholia of the lives of the burned-out working family.

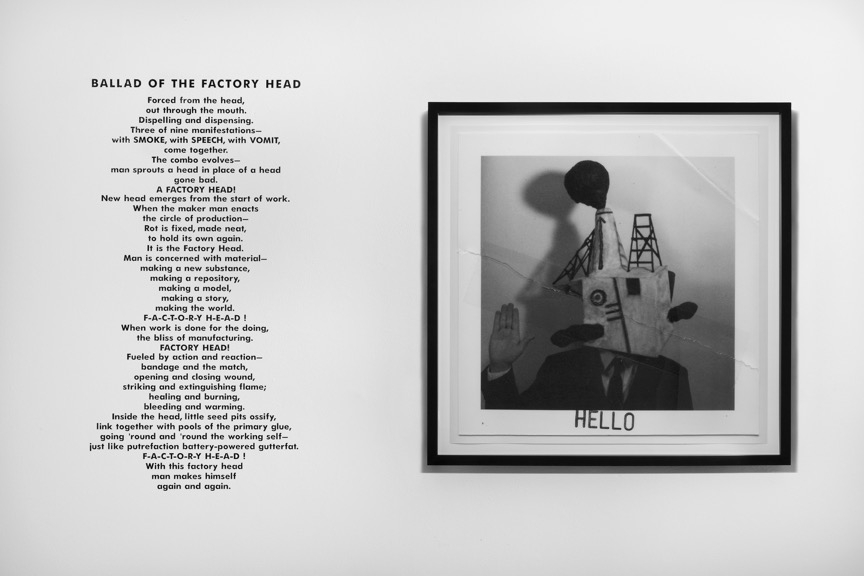

The diversity of Standfest’s art stretches to performance theater and is represented by an installation of three “masks,” called “Factory Heads,” that he employed in a performance at MOCAD with an accompanying musical composition of factory noise by created by Chris Butterfield and Mike Williams. In a sense Standfest’s “Factory Heads” sculptures and performance, covers of Bolshevik agitprop theater, are again in the Russian Constructivist spirit modeled after machine-like factory architecture with smokestacks and are accompanied by a Standfest poem that delineates the abject evolution of the working class.

Ryan Standfest, “Factory Head No.1,” archival inkjet on Epson, 32 ½ x 32 ½,” 2018

The quandary that we are left with in sorting out Standfest’s vision is the ultimate one that we are always left with: what to do with Modernism. Standfest’s comic satire of the machine age that left a wake of psychologically and physically maimed humans and a derelict social order was, at the same time, an emancipation from the tyranny of an old aristocratic ownership production and design. Standfest engages the Beckettian dilemma with a robustness which propels his excavations along with digging for and exposing another ironic gag.

Standfest is ruthlessly hilarious in his Dick Tracy-like comic strip satire of Adolf Loos’ famous critique “Ornament and Crime,” that helped define modernism, of how ornamentation in design is a crime against humanity. Standfest turns the scales, puts his detective Wolfe (Standfest’s version of Dick Tracy) on the case to expose the “villainous operation known as “International Style,” a crime wave of bare, spare, impersonal, and highly abstract architecture forced upon the innocent dwellers of the city by a group of European thugs.” Humorously dark critiques of the festishization of modernist design and designers, including of LeCorbusier and Mies van der Rohe abound, as well the opposite, fetishization of worker’s clothing and lifestyle that fill out and balance Standfest’s salient humor.

Ryan Standfest, “Unearthed Streetcar Rail,” gesso, graphite, ink, enamel on cardboard, 36” x 20,” 2018

Ryan Standfest: THIS MUST NOT BE THE PLACE YOU THOUGHT IT WOULD BE – at the Wayne State University Art Department Gallery – through December 7, 2018.