Two exhibitions offer a preponderance of material objects to make sense of the past

Psychedelic posters and printed matter, installation view

These days, the San Francisco Bay Area is neatly divided into two camps: you either are a tech bro, or you hate them. Back in my day as an errant Bay Area youth, there was a different kind of division: you either were a hippie, or you hated them. I, my friends, was certainly no hippie. Of course, in my time they weren’t even real hippies—although there were still a healthy number of Summer-of-Love burnouts quietly resisting the rising tide of capitalism. They were proto-hippies, the spawn of Baby Boomers, appropriating the fashion or rediscovering the music as it made its 20-year orbit in retrograde. Whether the die-hard originals or the new school posers, hippies were not, by any metrics, modern.

Isaac Abrams, Hello Dali (1965)

In fact, the seeming paradox between hippie and modern sensibilities provides the immediate tension of Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia—a sprawling exhibition initially organized by Andrew Blauvelt during his tenure at the Walker Art Center, which has subsequently followed him to be presented at the Cranbrook Art Museum, where he took up the mantle of Director last year. Hippies are commonly associated with back-to-the-land movements, eco-sustainability, and the timeless human yearning for peace and simplicity. Modernism is more concerned with technology, rapid progress and development, clean, modular design, and spare, white spaces.

Ken Isaacs, The Knowledge Box (1962-2009)

But, as Hippie Modernism proves, these odd bedfellows forged a powerful connection indeed (who wouldn’t hippies jump into bed with, really?), fused in a social pressure-cooker of late-60s radicalism and wartime unrest. This extremely dense exhibition is not so much an art show as it is a walk through time with an art-historical lens—one which captures facets of hippie culture that have been elided by a typical focus on the flashier and more simplistic culture of drugs, fashion, rock-and-roll, and sex.

Works by Haus-Rucker-Co, (installation view)

These facets are loosely divided into three galleries: Turn On, Tune In, and Drop Out. Each of these examines a dominant theme of the time period, roughly the mid-1960s through the early 1970s—that of consciousness-raising on an individual level, social awareness on a geo-political level, and active rejection of certain cultural pressure of normativity and technological progress (to name a few). The objects and information on display demonstrate a deep interest in modern design not as an aesthetic exercise but a practical one, as applied to communal and off-the-grid living, mobile housing, and sustainable infrastructure; technology, not at as means of warfare but as a means for more direct powers of computing and personal representation; and tool use as a mechanism for exploring the inner workings of the mind. The exhibition, which occupies the entire main floor of Cranbrook is veritably papered in schematics of ergonomic living solutions, imagined vehicles, and visions of bio-domes (not to mention an actual geodesic dome that features an interactive and highly trance-inducing installation, The Ultimate Painting, by Clark Richert, Richard Kallweit, Gene Bernofsky, JoAnn Bernofsky, and Charles DiJulio.

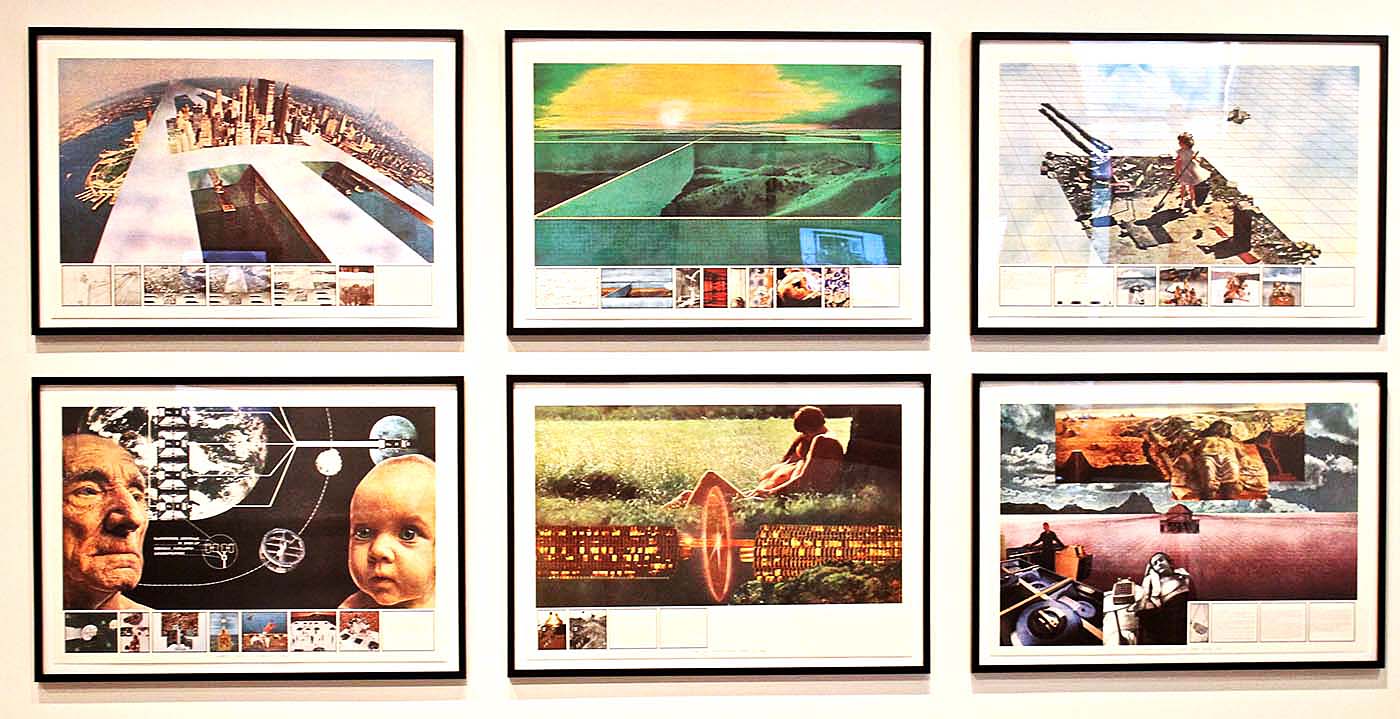

Superstudio, Prints from the Superstudio Series (1969-1973)

Many of the works bear collective credits, the products of communal discussion and creative efforts; many have the earmarks of what today would be considered “social practice art,” but at the time was considered radical politics—leaving the viewer to marvel at the subsequent commoditization of art in the 1970s and 1980s to defang its inherent power as a social catalyst! There are, as one might imagine, a room splashed with dozens of examples of psychedelic poster art—but the collection is not limited to the vivid band promo materials that probably still line the halls of the Fillmore (if they haven’t turned it into a vape bar or something). Rather, there is a kind of radical parallel to the Madison Avenue advertising culture that was taking hold of the market—a conscious and deliberate exploration of type, color, and imagery as a mechanism to promulgate messaging. There are, undeniably, quite a number of chill spaces distributed around the exhibition, and a good thing, too—with so much going on, the opportunities to stop, drop, and contemplate are welcome interruptions. These include a handful of audio/video screening rooms, a Relaxation Cube from Nomadic Furniture 1 (1973) with floor cushions and a soothing slide show, and a full-gallery installation of a work by Hélio Oiticica and Neville D’Almeida, CC5 Hendrixwar/Cosmococa Programa-in-Progress, complete with hammocks.

John Glick: A Legacy in Clay, installation view

John Glick: A Legacy in Clay @ Cranbrook Art Museum

It bears mentioning that Hippie Modernism is not the only spectacular exhibition currently on display at Cranbrook Art Museum, though it certainly warrants a visit all on its own. A career survey of ceramic artist John Glick—John Glick: A Legacy in Clay—is a dazzling walk through the life work of a virtuosic artist who managed to find fresh takes on vessels and forms as old as human society. From the wall of teapots, to the hanging friezes, to the physical timeline of Glick’s singular and beautiful ceramic forms, laid out in an engaging and accessible 360-degree display that mimics the sort of tables where they might otherwise be found, the Glick retrospective offers eye candy at every turn.

Food for thought, vessels for food, and much to take in at Cranbrook Art Museum!