Elizabeth Youngblood :: New Knowns :: New Work @ Birmingham Bloomfield Art Center

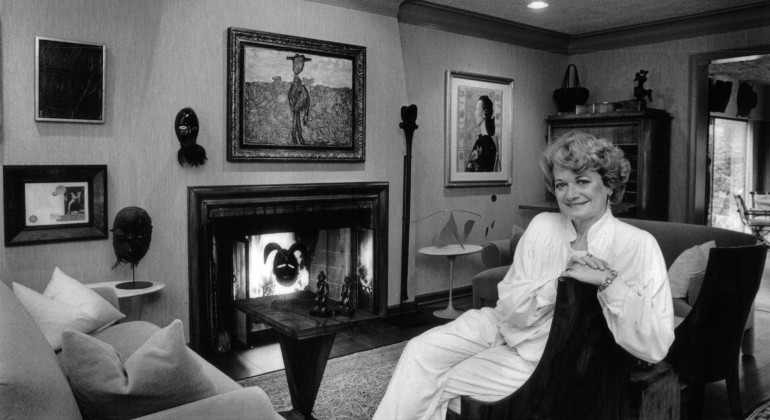

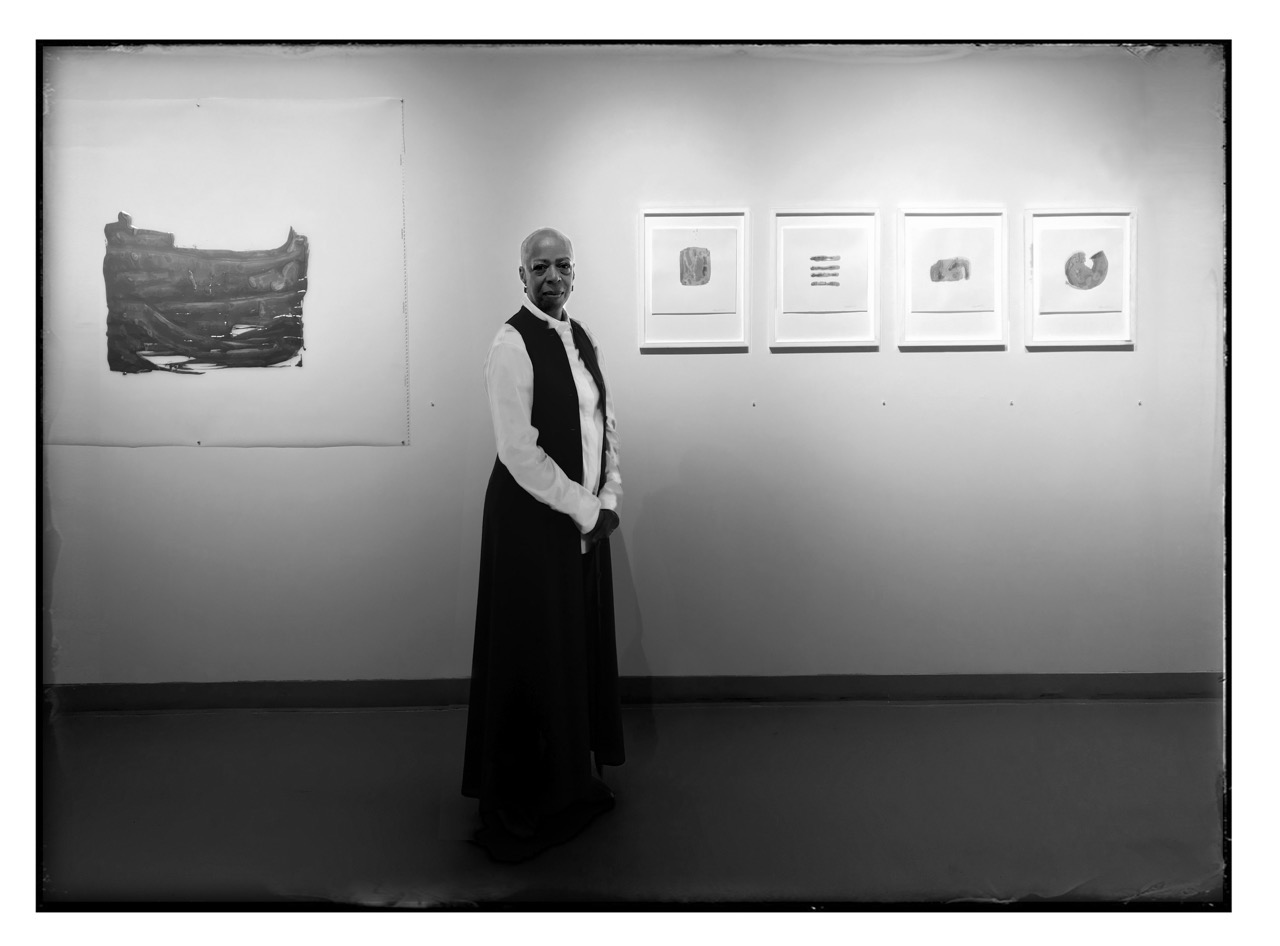

Elizabeth Youngblood at BBAC exhibition opening, photo courtesy of Stewart Shevin

Many years ago, Elizabeth Youngblood wrapped a tiny silver spoon in cotton swaddling. Perhaps it was exhibited in a show of her work but at the time I saw it in her studio at the vast complex now known as the Russell Industrial Center. Designed by Albert Kahn and John William Murray for J.W. Murray Mfg., his automotive sheet metal manufacturing company, the Russell Industrial Center now houses artist’s studios, small businesses and cottage industries and shops, but it was then known as “an apartment house for industry.” The irony of this tiny swaddled silver spoon having been created in an enormous automotive factory that stamped car bodies, did not escape me at the time. As a tiny conceptual sculpture, it was very moving to me. Youngblood’s mother had recently passed and we talked of her mother’s influence on her art, and I’ve often thought since then about the vulnerable swaddled teaspoon as an image of tenderness and delicate caring as well as protection against the monstrous, repetitive brutality of big industry.

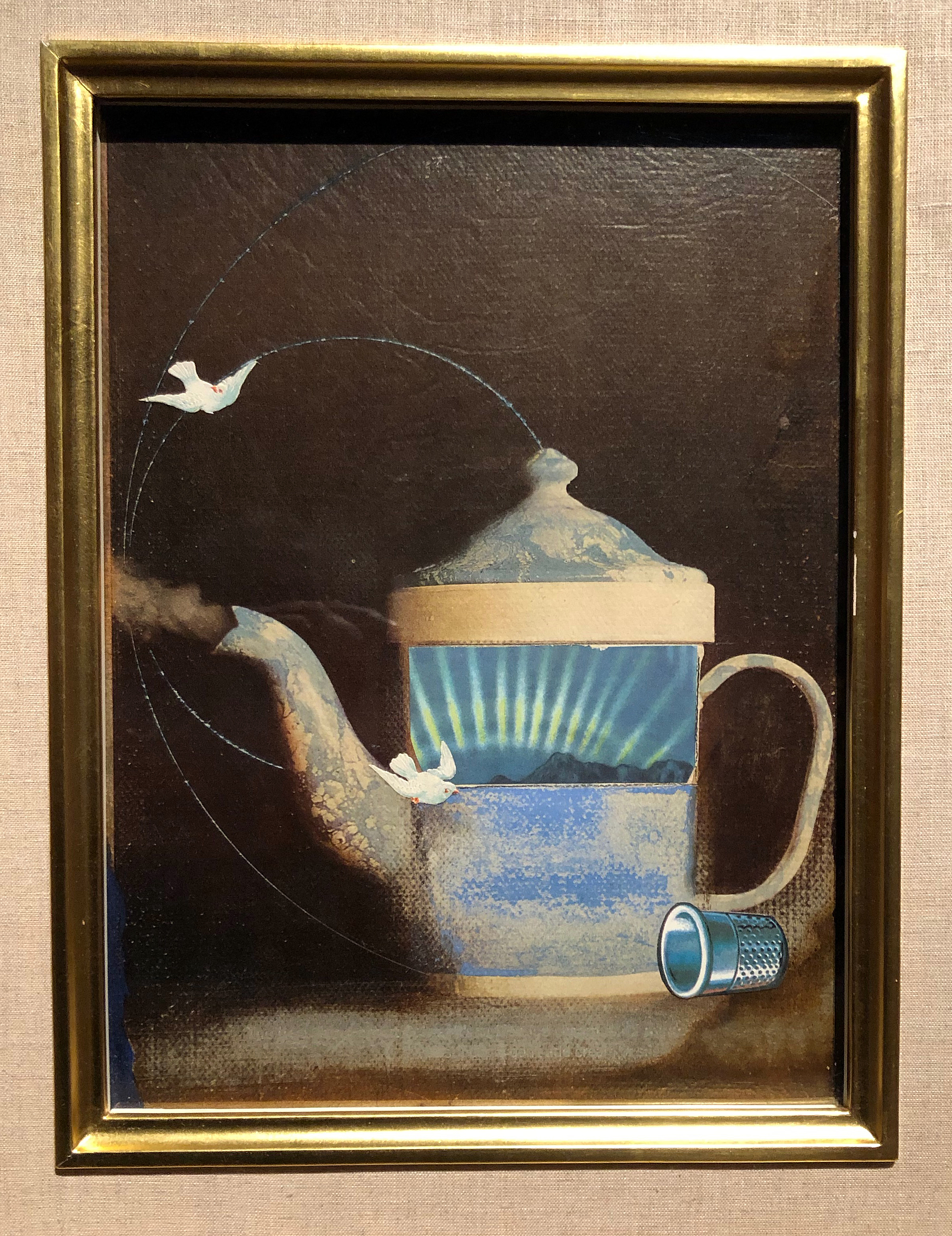

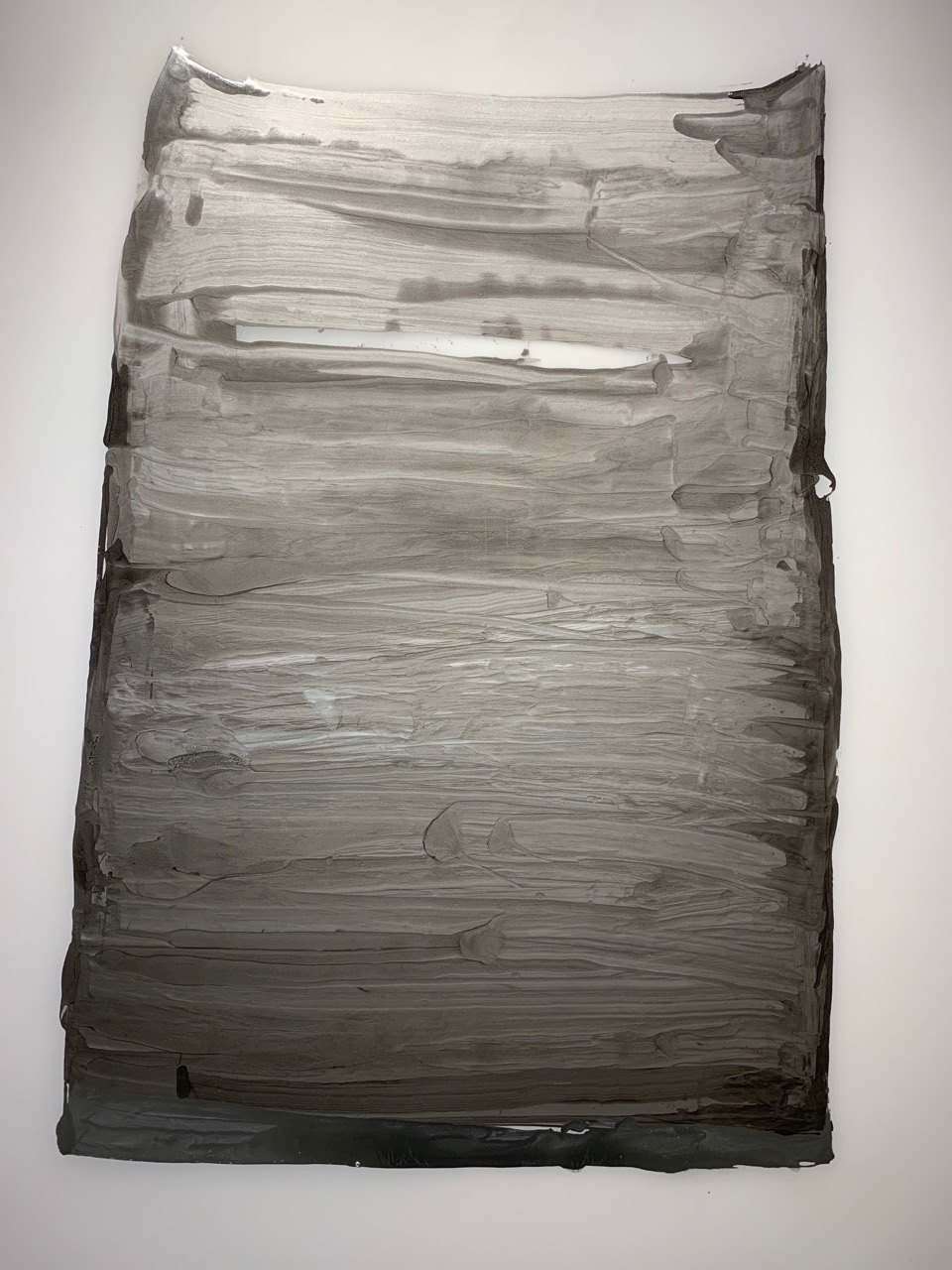

Elizabeth Youngblood, “Obelisk with Window,” Paint, Mylar. 43”x 55,” 2018 – Remaining images courtesy of Glen Mannisto

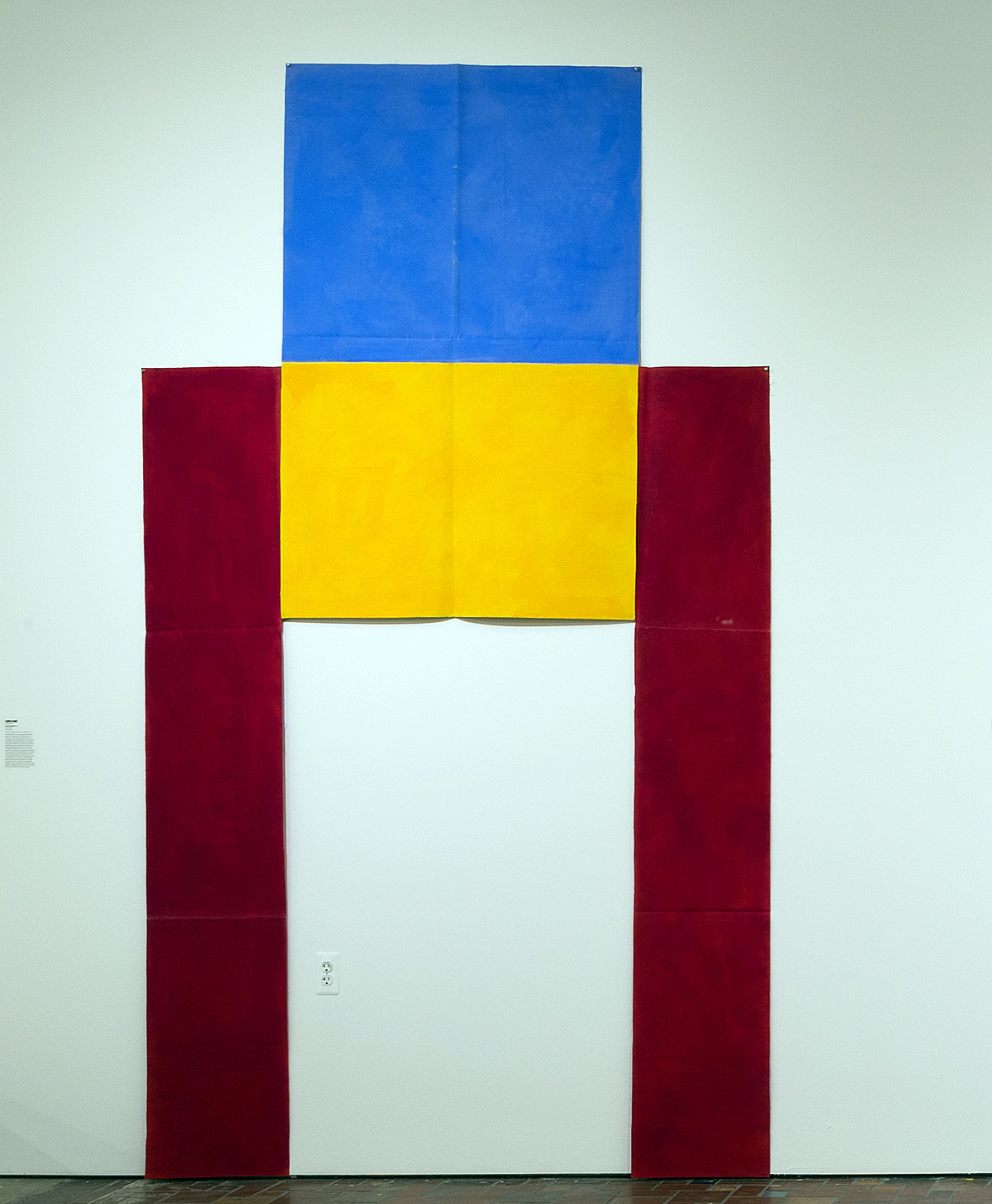

The current Birmingham Bloomfield Art Center’s exhibition, “New Knowns :: New Work :: Elizabeth Youngblood,” is a collection of over twenty-five paintings, drawings and small sculptures. The paintings are silver paint on Mylar or paper; the sculptures are small drawings made with wire and the drawings are ink on paper. The silver paintings hark back to Youngblood’s swaddled teaspoon. Each work in the show seems to turn on the idea of swaddling or wrapping. Thick, creamy silver paint, strangely sensuous, is applied in a gesture of wrapping, as if an object is being contained, or protected by swaths of paint. The gestural swaths accumulate and become images that are abstracted, slightly askew shapes, some almost container-like, others abbreviated marks as if a beginning of something. They are forms that are on the verge of meaning, and in their gestural immediacy they deny machine reproduction, asserting the enigma of individual identity.

The shape of “Obelisk” suggests a container, something as small as a cup or as large as a nuclear power plant such as Fermi in SE Michigan which it resembles. Appearing almost logo like, its lack of symmetry proclaims its disconnect from the world of branding and independence from the commercial graphic world in which Youngblood has worked and knows well. Throughout “New Knowns::New Work,” Youngblood is always asserting the individual hand, that character of the eccentric hand. The wabi sabi of personal gesture, the imperfect and anti-engineered or anti-corporate.

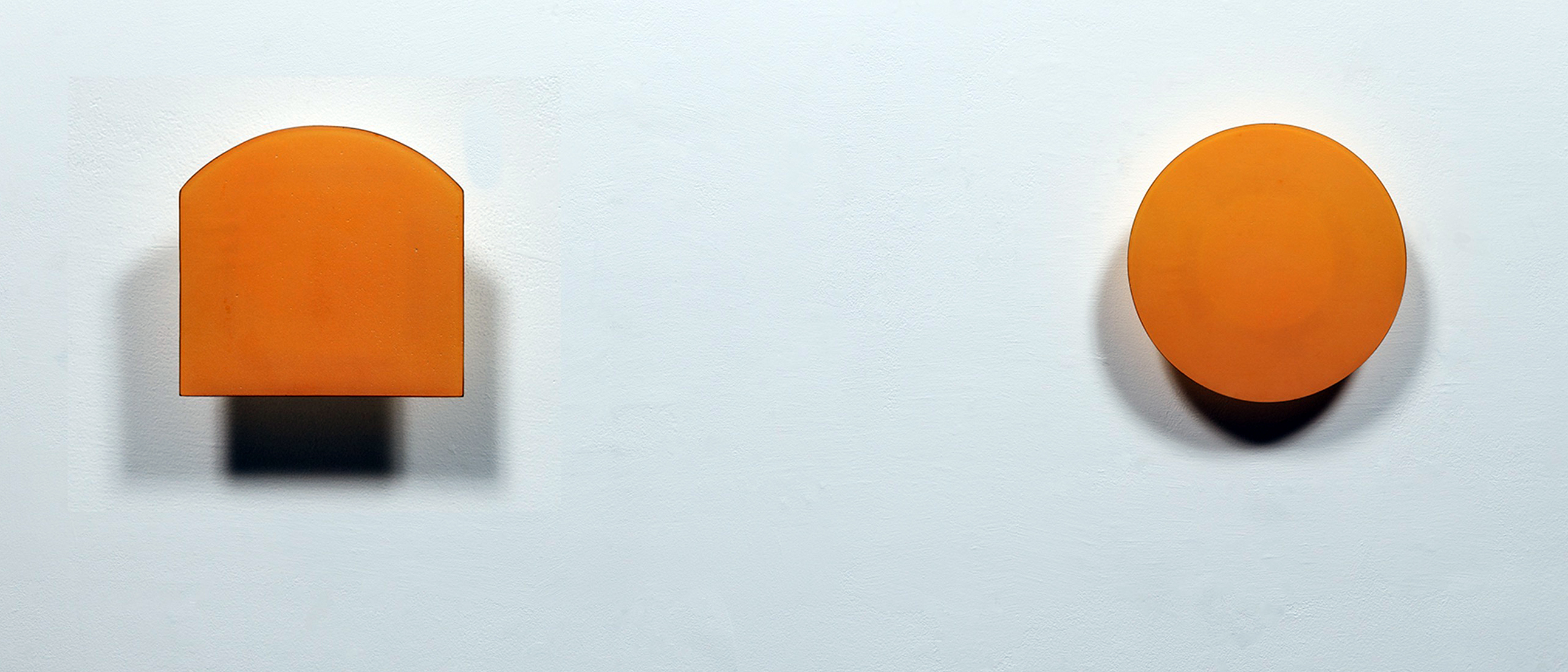

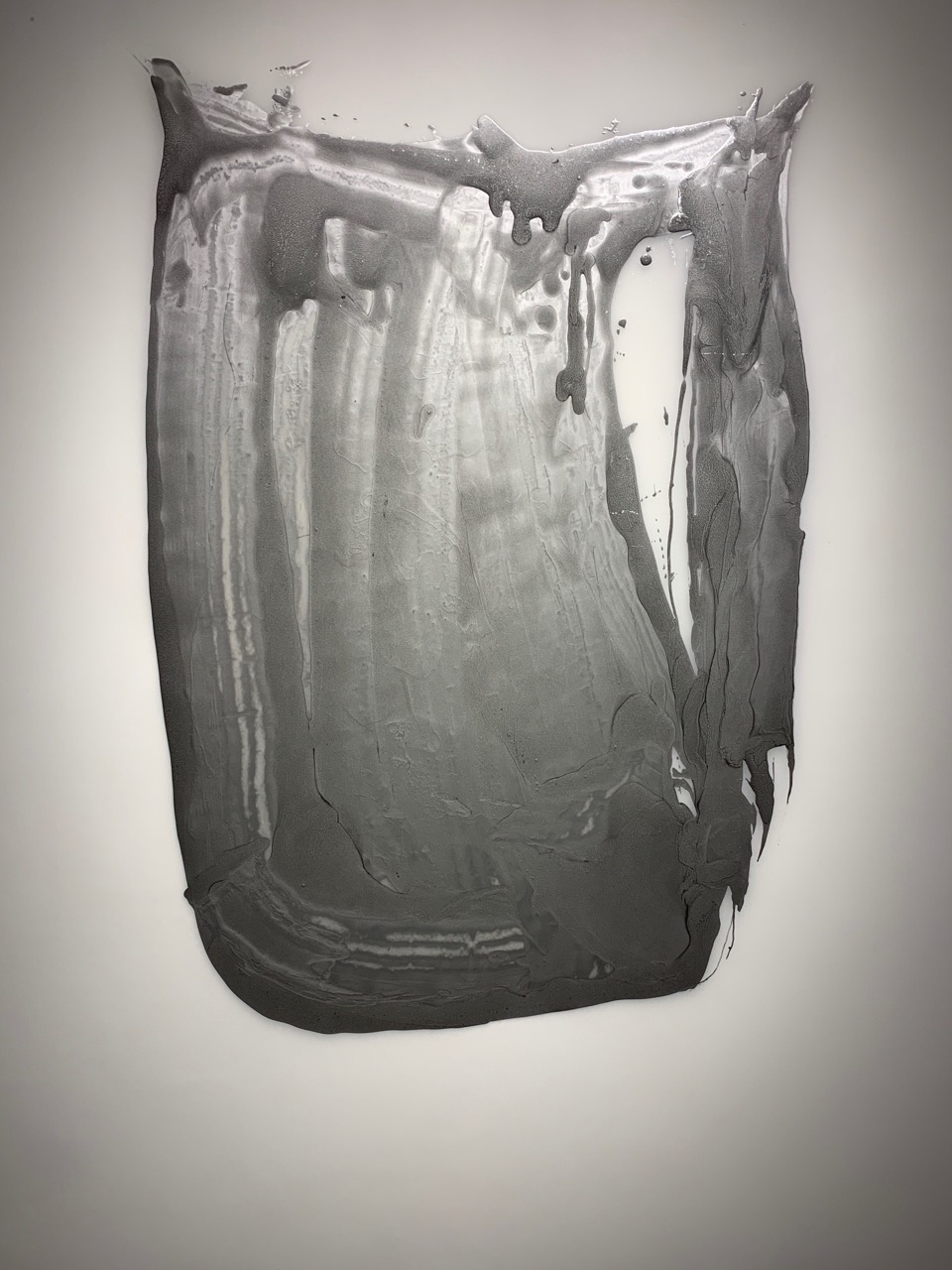

Elizabeth Youngblood, “Yet Untitled,” Paint, Mylar, 44”x 54”, 2018

The larger paintings reveal that imperfection best. “Yet Untitled,” the perfect title, because it is a thing in process of becoming, with drips and vertical wrapping brush strokes, draping the illusion of becoming a vessel or a contained identity. The metallic paint seems almost primal and molten, pre-industrial and pre-corporate. To assert the connection with the very early swaddled teaspoon is “Swaddle 1,” which also is in the process of becoming and containing, with swathes of reflective paint articulating its form suggesting a tail of wrapping swaddle loosely hanging.

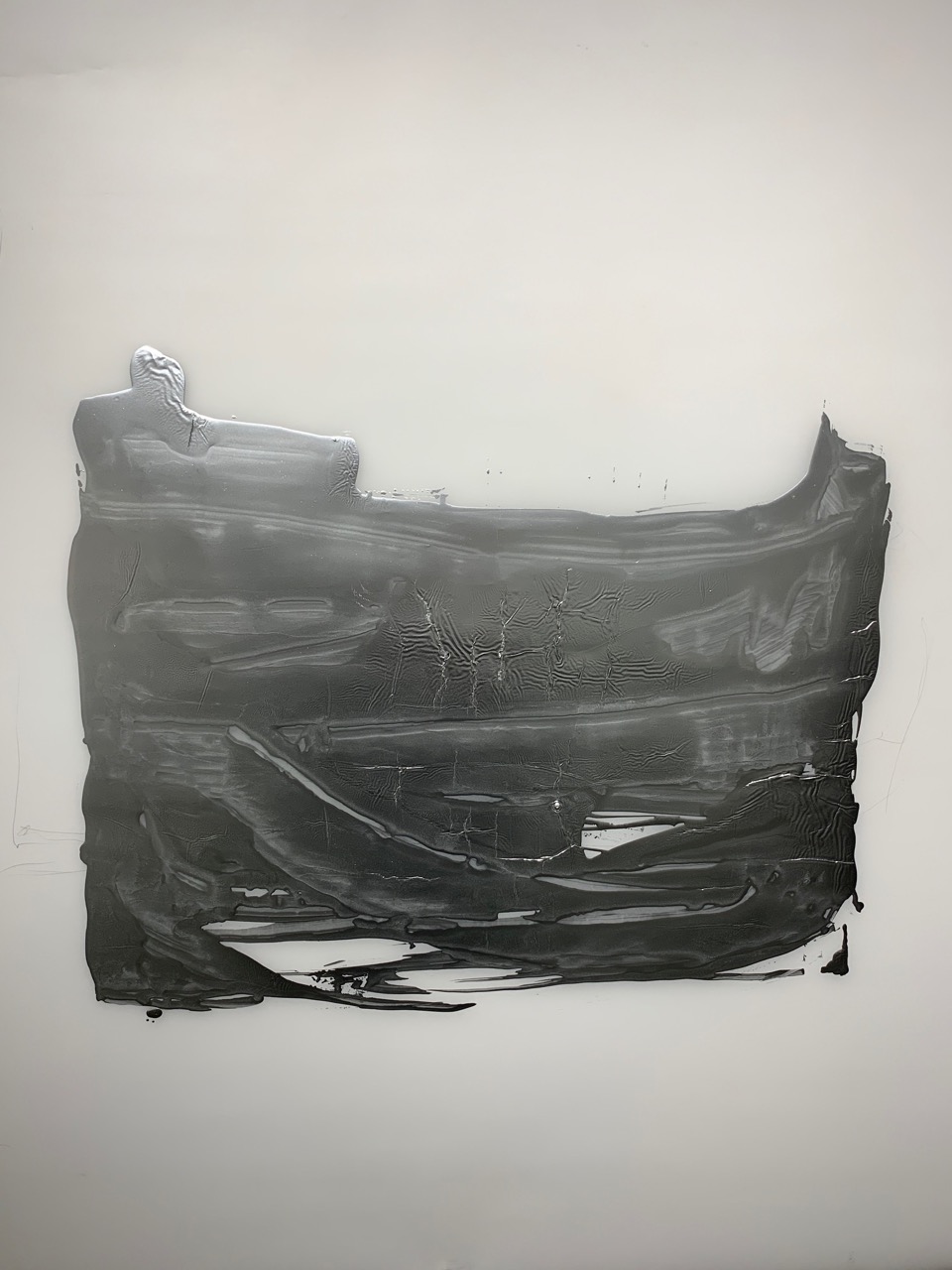

Many of the paintings suggest this sense of becoming or evolution, and even a sense of failure to become and an unraveling or failure of material. “Silver and Graphite 1,” beautiful in its chance patterns of curing and drying, is a composed of a mixture of graphite and metallic paint whose process of becoming has been arrested, the paint’s coagulating and dripping is remarkable in its incomplete state.

Elizabeth Youngblood, “Silver & Graphite 1,” Mixed Media, 55” x 45,” 2018

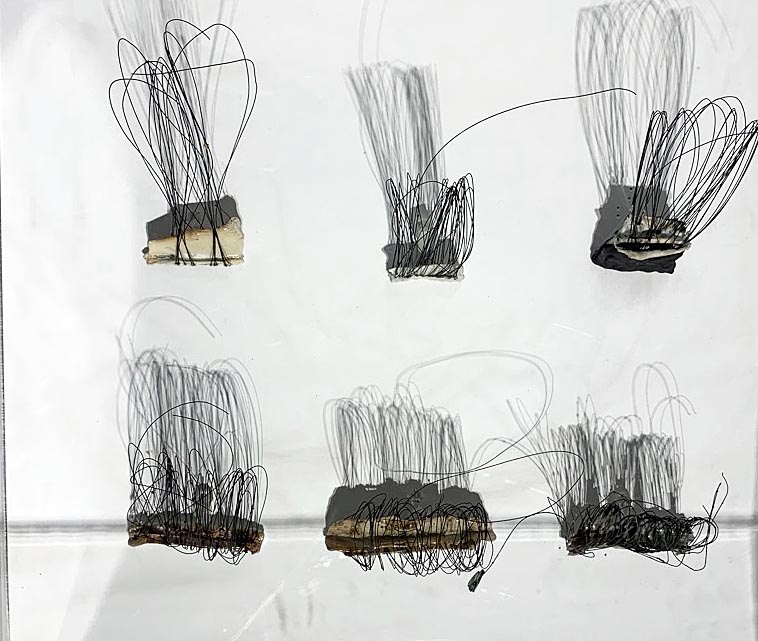

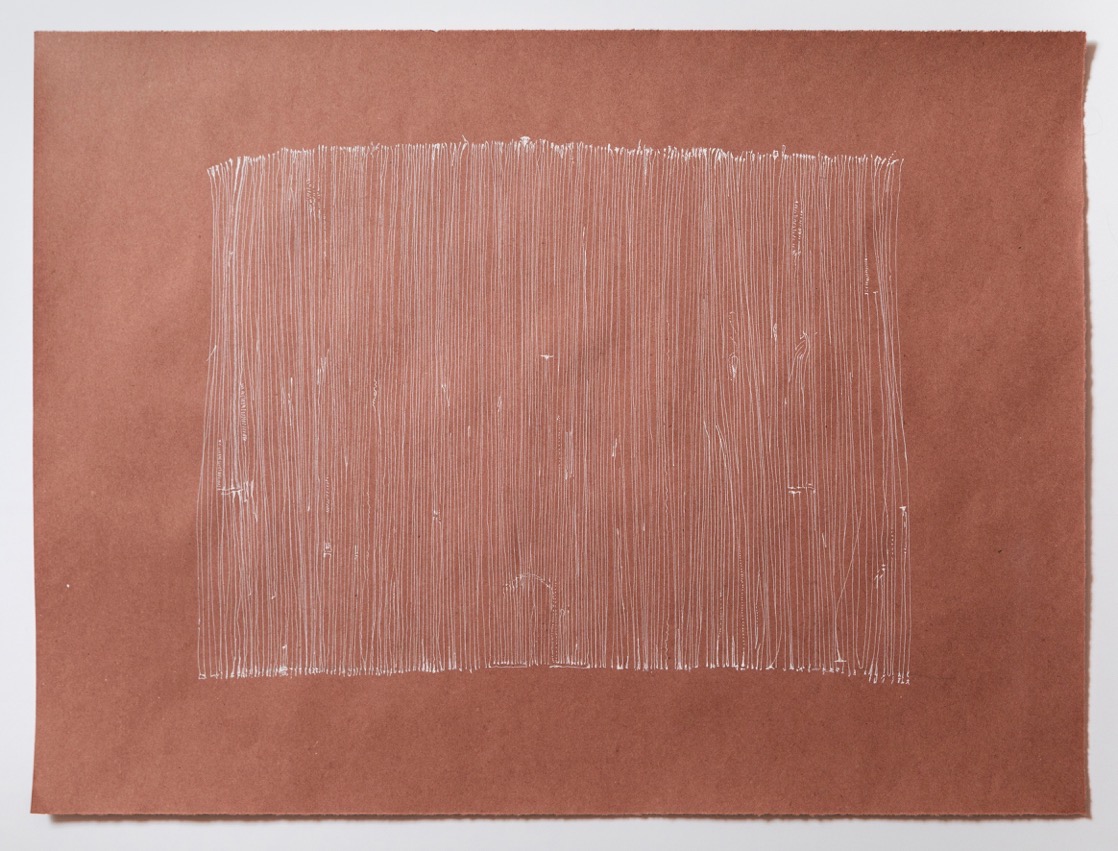

Both the “Wire Drawings” and ink drawings exhibit Youngblood’s considerable sensitivity and patient engagement, commitment and deliberate execution of line and form. The fragile wire drawings are coiled and anchored in a porcelain base and express a similar imperfection to the metallic paint paintings and are not machine coiled but seem scribbled and overlapping. While they might suggest figurative drawings, their intrigue is their specific wonky lack of balance. Yet each has a delicate presence and are read by their ever slight (animist?) difference. The same holds true for the ink drawings. Wrought like nerve endings, the inked lines almost quiver by proximity and some fail by some metaphorical disturbance of hand or mind and simply express the fragility of process.

Elizabeth Youngblood, “Six Wire Drawings,” Porcelain, wire, 2016

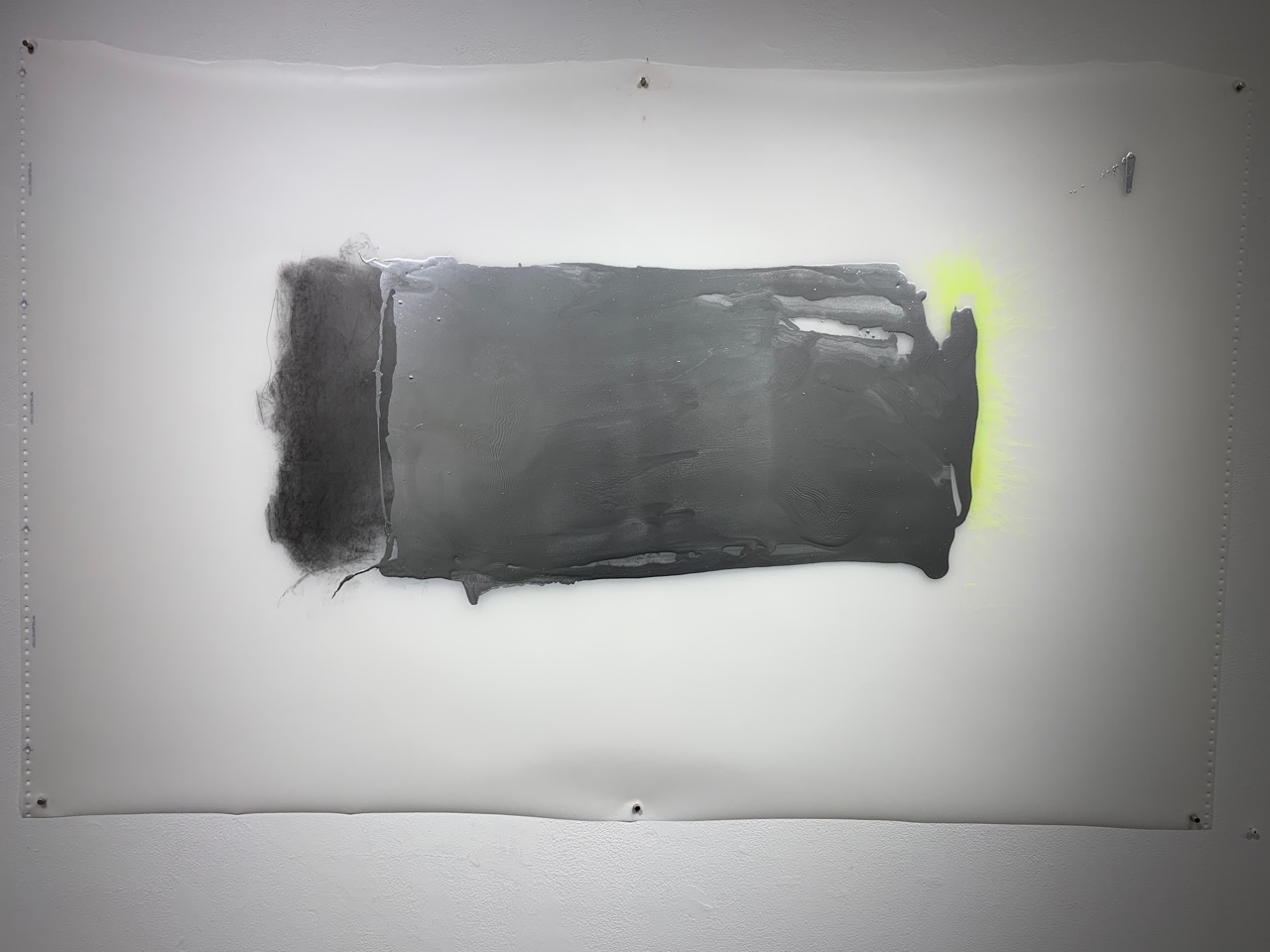

Some of the metallic paintings forgo the swaddling brushstrokes and simply allow the soft silvery glow of the molten-like paint to show itself by contrast. The beauty of a rough swatch of metallic paint bordered by a cloud of graphite and a line of chartreuse on the background of Mylar substrate is a wonderful invention by itself.

Elizabeth Youngblood, “+Graphite and Chartreuse,” Graphite, Mylar, 55” x 34.25,” 2019

The overall orbit of Youngblood’s “New Knowns :: New Works” describes her physical engagement with mark making, with being engaged, with touching materials and creating processes. In all of the works there is a palpable sense of her presence in the materials rather than with the spectacle. We read the visual results metaphorically but experience the work as a path, not a fully known, but “new known,” and realize that the process of seeing is a process and is continuous.

Elizabeth Youngblood, “Clare Gatto,” ink, paper, 20” x 15,” 2016

Elizabeth Youngblood, New Knowns :: New Works, Through June 6, 2019

Birmingham Bloomfield Art Center