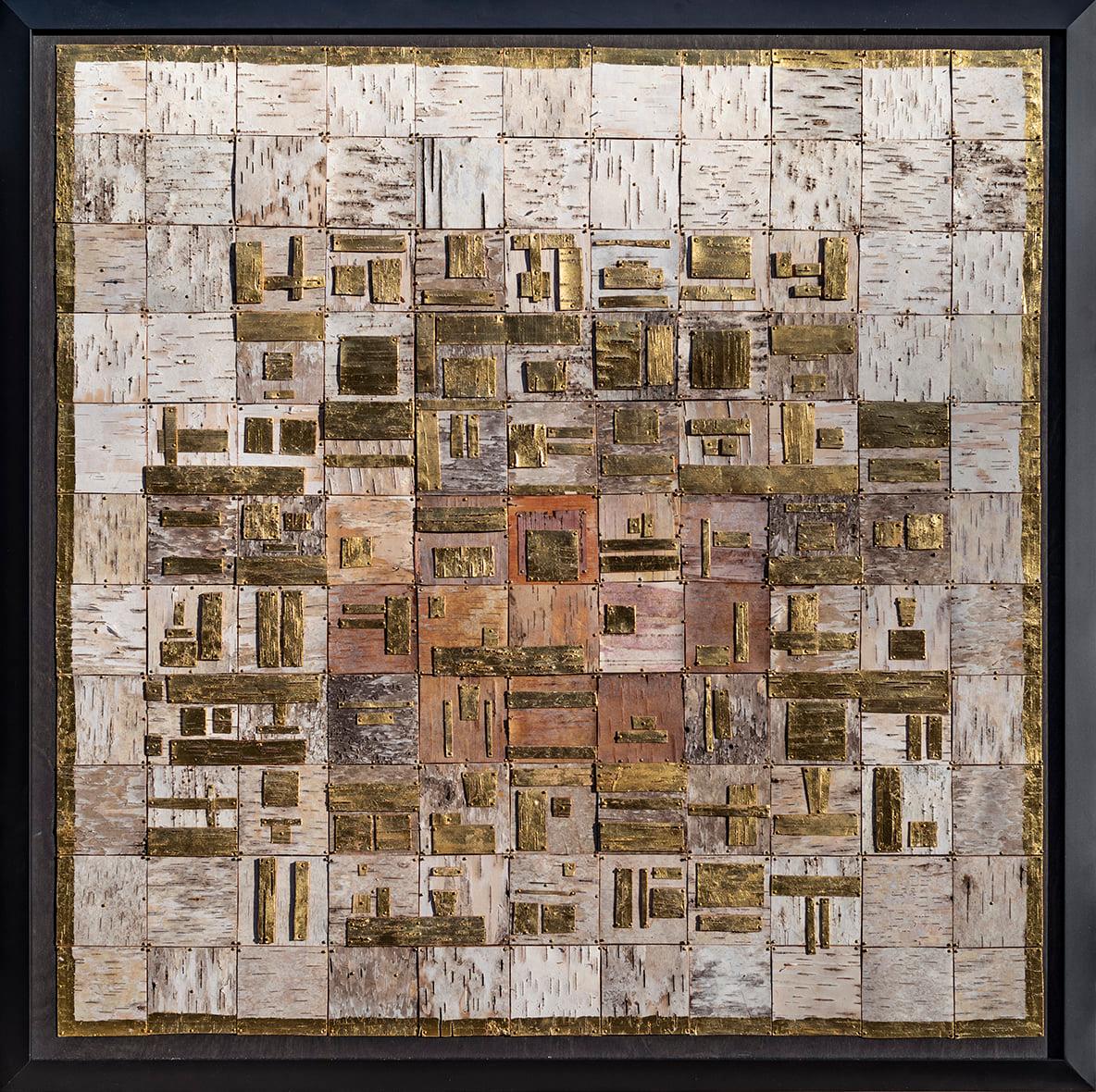

Installation image, Many Voices: The Fine Art of Craft @ BBAC

If there ever was a bright line of distinction between what we call contemporary fine art and what is now considered to be craft, that line has long ago been crossed and obliterated. The mixed bag of artifacts on display in the exhibition at Birmingham Bloomfield Art Center from May 6 to June 2 illustrates this, with a range of objects and images that contrast the useful with the expressive, the carefully crafted with the emotionally contingent. “Many Voices: The Fine Art of Craft” takes us on a tour of the increasingly porous borders between objects that can claim to be fine art, but qualify as craft only because they refer tangentially to traditional crafts and finely handmade objects that are intended for utilitarian purposes.

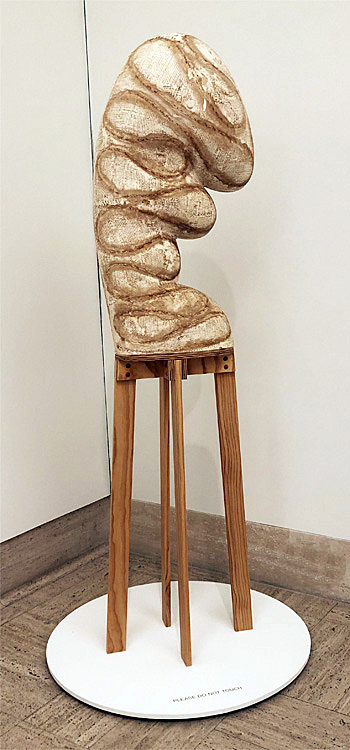

Wall Vessel V, Constance Compton Pappas, unfired clay, cedar

Balanced, Constance Compton Pappas, cedar, plaster, clay

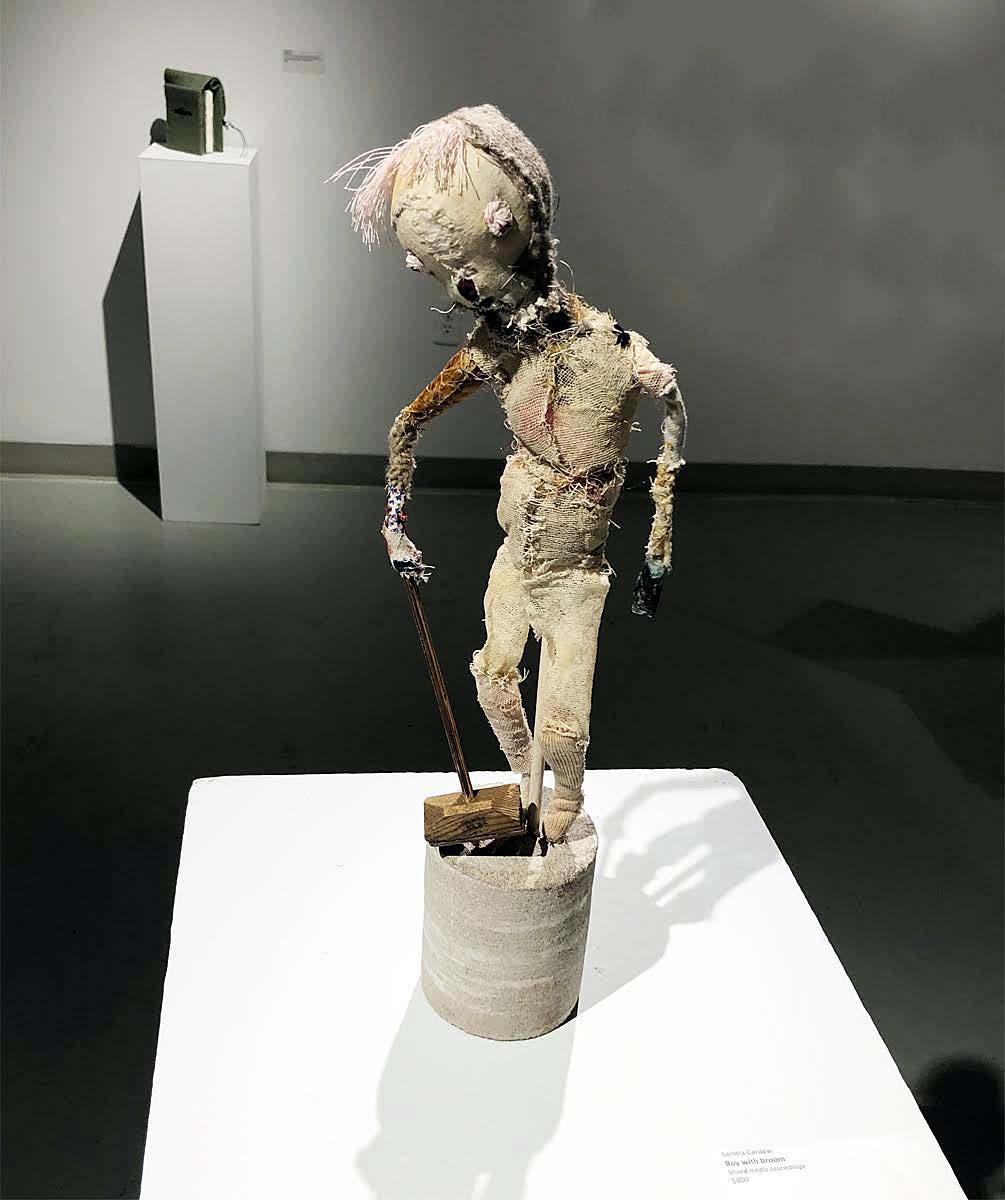

The objects in the exhibition fall roughly into two categories. Works by artists such as Constance Compton Pappas, Dylan Strzynski, Sandra Cardew and Sharon Harper privilege the expressive properties of the materials and push them to the limits of their identity. Often there is a toy-like mood to this work. Any pretense to utility is deeply submerged beneath the artists’ emotionally poignant themes. Pappas’s wall-mounted, naturally irregular wooden shelves support clay objects that only refer to vessels, and certainly were never intended to function. They are signs for cups and the considerable pleasure to be derived from them rests upon their rough, stony texture contrasted with the irregularities of the wooden support. Elsewhere in the gallery, Pappas uses the abstract shapes of 3 cast plaster houses, again placed on a raw wood pedestal in a stack, entitled Balanced, that implies a state of wonky precarity. Dylan Strzynski’s playful, barn-red house model, Attic, made of wood, sticks and wire, suggests a kind of Baba Yaga cottage on legs, poised to jump off its pedestal in pursuit of the viewer. Sandra Cardew’s Boy with Broom continues the preoccupation with play. The subdued color and rough fabric of the golem-child is both a little funny and a little ominous. Sharon Harper’s Pink Trailer makes an interesting kind of mini-installation by hanging a 2-dimensional photo landscape on the wall behind a diminutive clay trailer, suggesting the possibility of travel through wide open spaces.

Attic, Dylan Strzynski, wood, paint, sticks, wire, string

Sandra Cardew, Boy with Broom, mixed media assemblage

Danielle Bodine’s wall installation, Celestial Dance, offers a floating population of tiny woven wire and paper elements that might claim to be plankton or might be satellites. Whatever they are, their yellow starlike shapes weightlessly orbit a larger, spiky planetary body, and cast lively shadows on the wall. The basketry techniques that Bodine has employed for nearly 20 years allow her complete freedom to invent these minute entities in three dimensions.

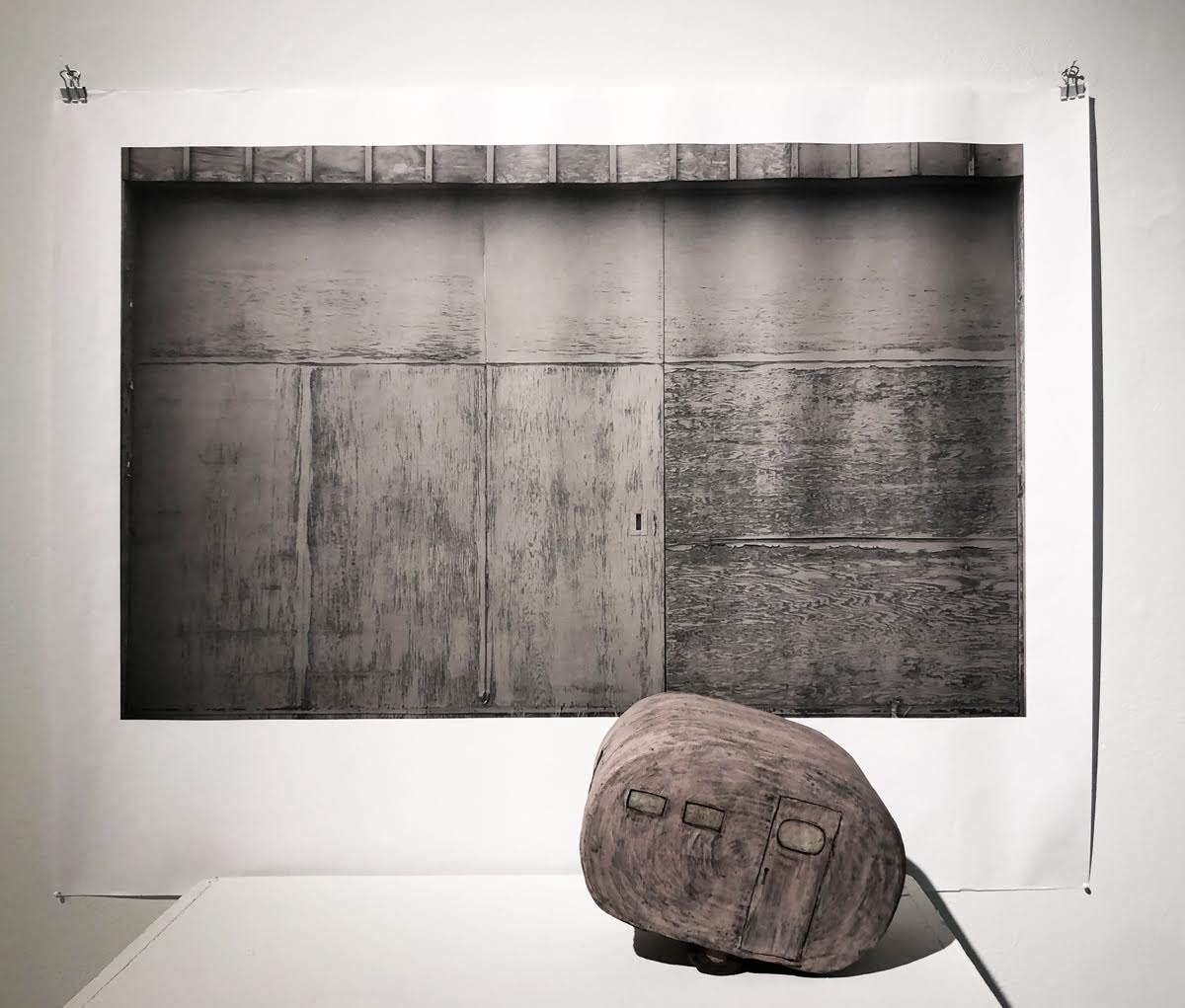

Sharon Harper, Pink Trailer, low fire clay, photograph

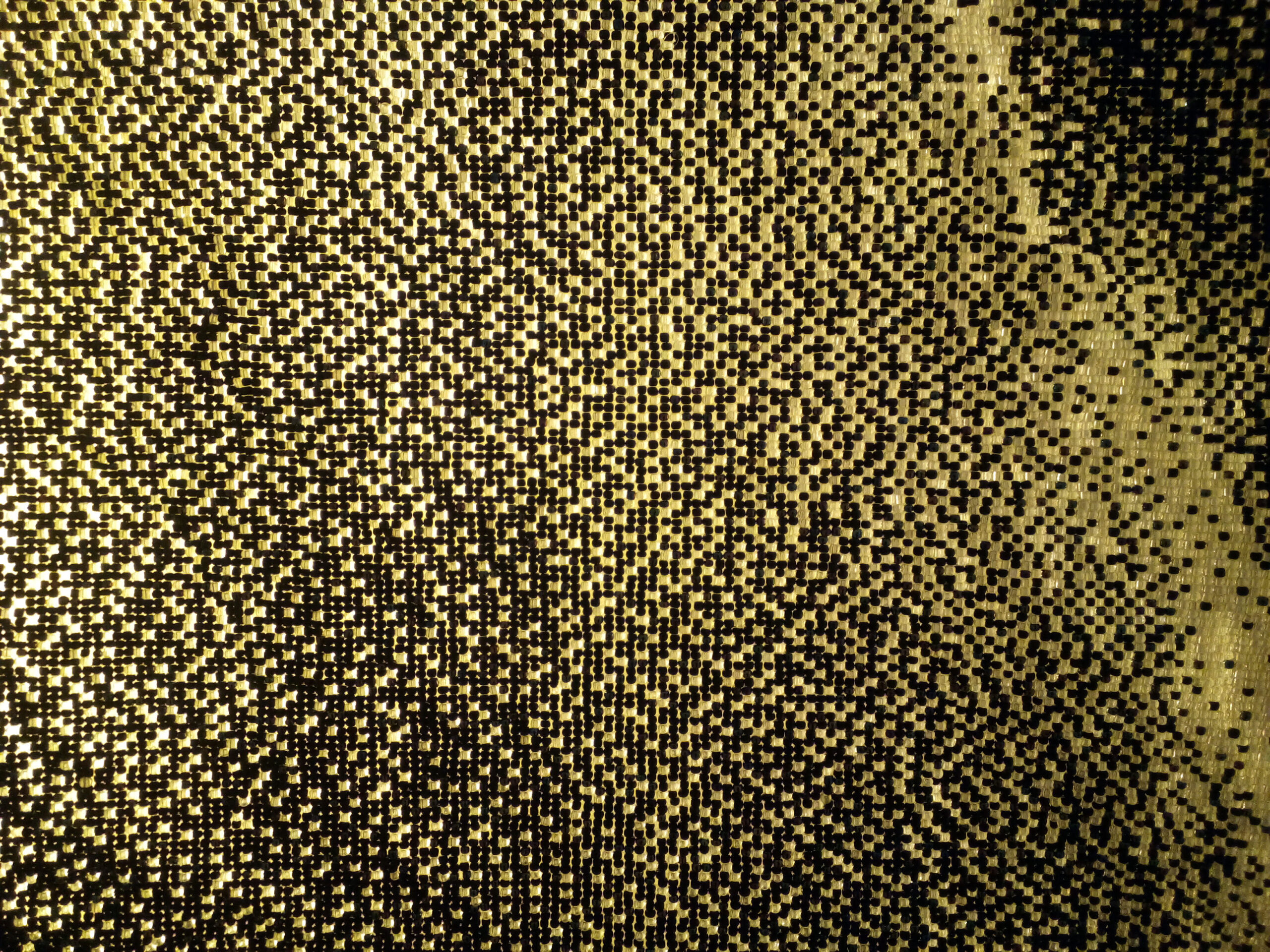

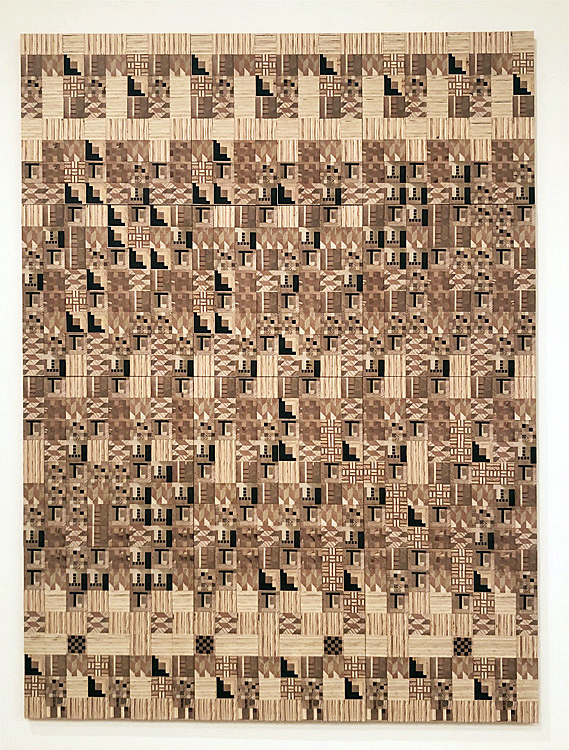

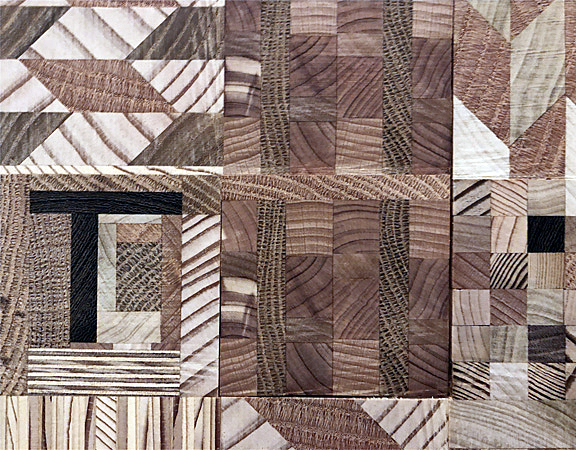

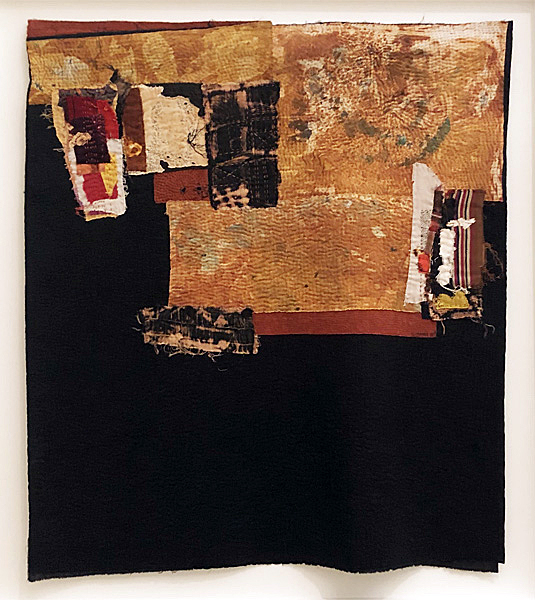

The fiber artist Carole Harris, who has several works in the show, continues to be in a class by herself. From her beginnings as a more conventional quilter, Harris has traveled far and wide, taking inspiration from Asia, Africa and beyond. Her carefully composed, expressively dyed and stitched formal abstractions are emotionally resonant and reliably satisfying. The artist employs a mix of fabrics and papers, along with hand-stitching and applique, with the easy virtuosity of long practice.

Danielle Bodine, Celestial Dance, mulberry and recycled papers cast on Malaysian baskets, removed, stitched, painted, stamped, waxed linen coiled objects, plastic tubes, beads,

Carol Harris, Yesterdays, quilted collage

Russ Orlando’s pebbly pastel ceramic urn-on-a-table, Finding #171, is covered by contrasting buttons and frogs wired to the substrate. The vessel evokes a friendly presence: it wants to know and be known.

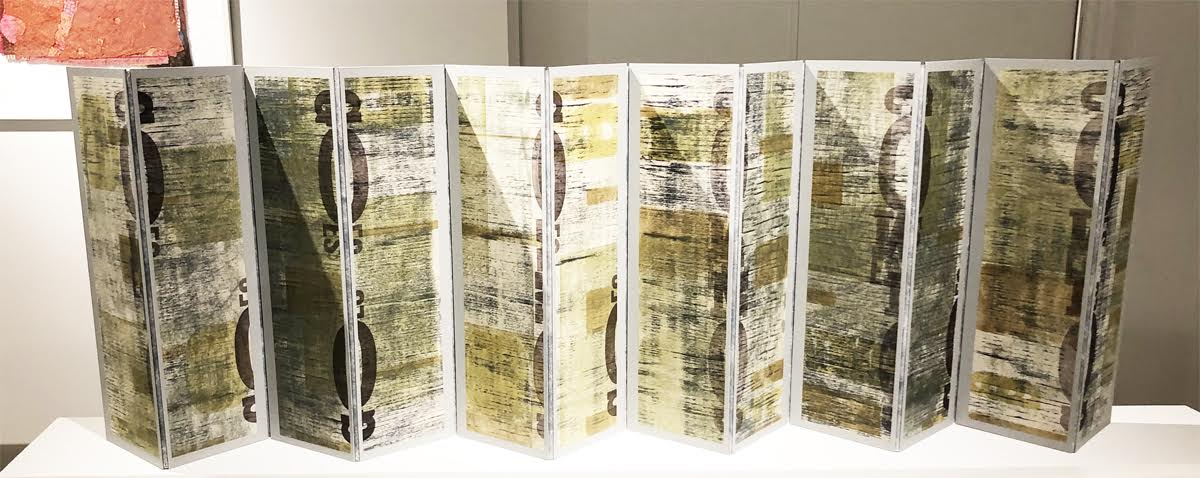

Two artists in “Many Voices,” Lynn Avadenka and Karen Baldner, are masters in the craft bookmaking/printing, whose work perfectly balances function and form, though to different ends. Baldner’s snaky, wiggly rice paper centipede of a book, Letting Go, shows how exquisite technique can pair with creative expressiveness to yield an original effect. The restrained elegance of Lynne Avadenka’s handmade screen Comes and Goes III demonstrates that utility and esthetic pleasure need not be mutually exclusive.

Karen Baldner, Letting Go, piano hinge binding with horsehair, mixed media print transfers

Lynne Avadenka, Comes and Goes III, unique folding screen, relief printing, letter press, typewriting, book board, Tyvek

Among the objects in this collection, Colin Tury’s handsome, minimalist metal LT Chair hews closest to traditional ideas of craft, as does Cory Robinson’s smoothly crafted side table, which looks as if it belongs in a hip, mid-century bachelor’s lair.

Colin Tury, LT Chair, aluminum, steel

Cory Robinson, Canberra Table, American black walnut

In this time and place, and as illustrated by the artists in “Many Voices,” the categorization of an object as “art” or “craft” has become less and less useful. Historically, crafts based on highly technical knowledge—ceramics, fiber glass and the like –have been assigned a lesser status because of their identity as objects of utility. It is undeniable too that many of these crafts were practiced by women, which devalued them in the estimation of collectors and galleries. Fortunately, those preconceptions are receding into the past, as artists progress toward a future that is more open to new forms and voices, new materials and subjects.

The artists in “Many Voices: The Fine Art of Craft” are: Kathrine Allen Coleman, Lynne Avadenka, Karen Baldner, Danielle Bodine, Sandra Cardew, Candace Compton Pappas, Nathan Grubich, Christine Hagedorn, Sharon Harper, Carole Harris, Amanda St. Hillaire, Sherry Moore, Russ Orlando, Cory Robinson, Dylan Strzynski, Colin Tury.

Many Voices: The Fine Art of Craft at the Birmingham Bloomfield Art Center runs until June 2, 2022.