Selections from the Mark and Ora Hirsch Pescovitz at Oakland University Art Gallery

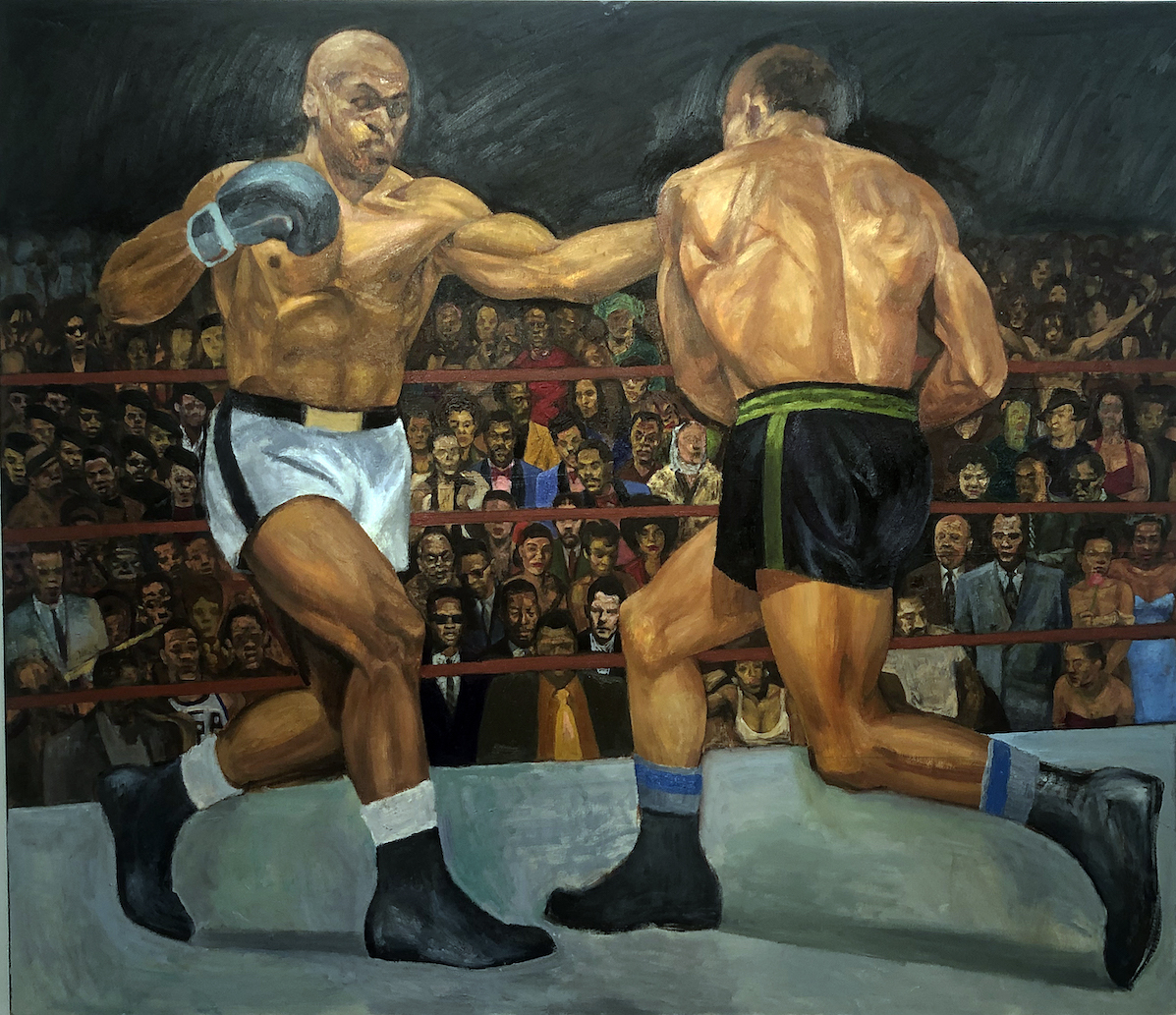

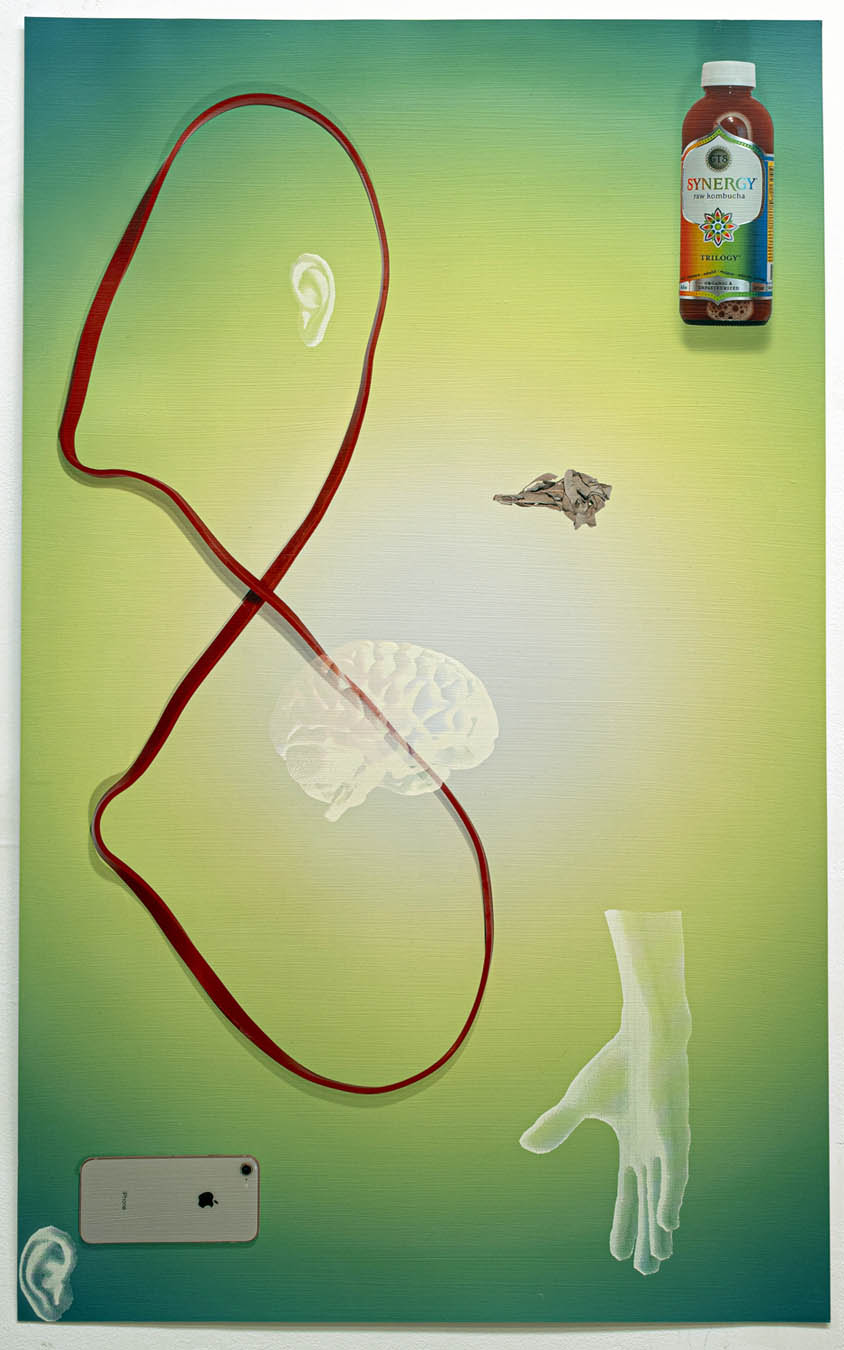

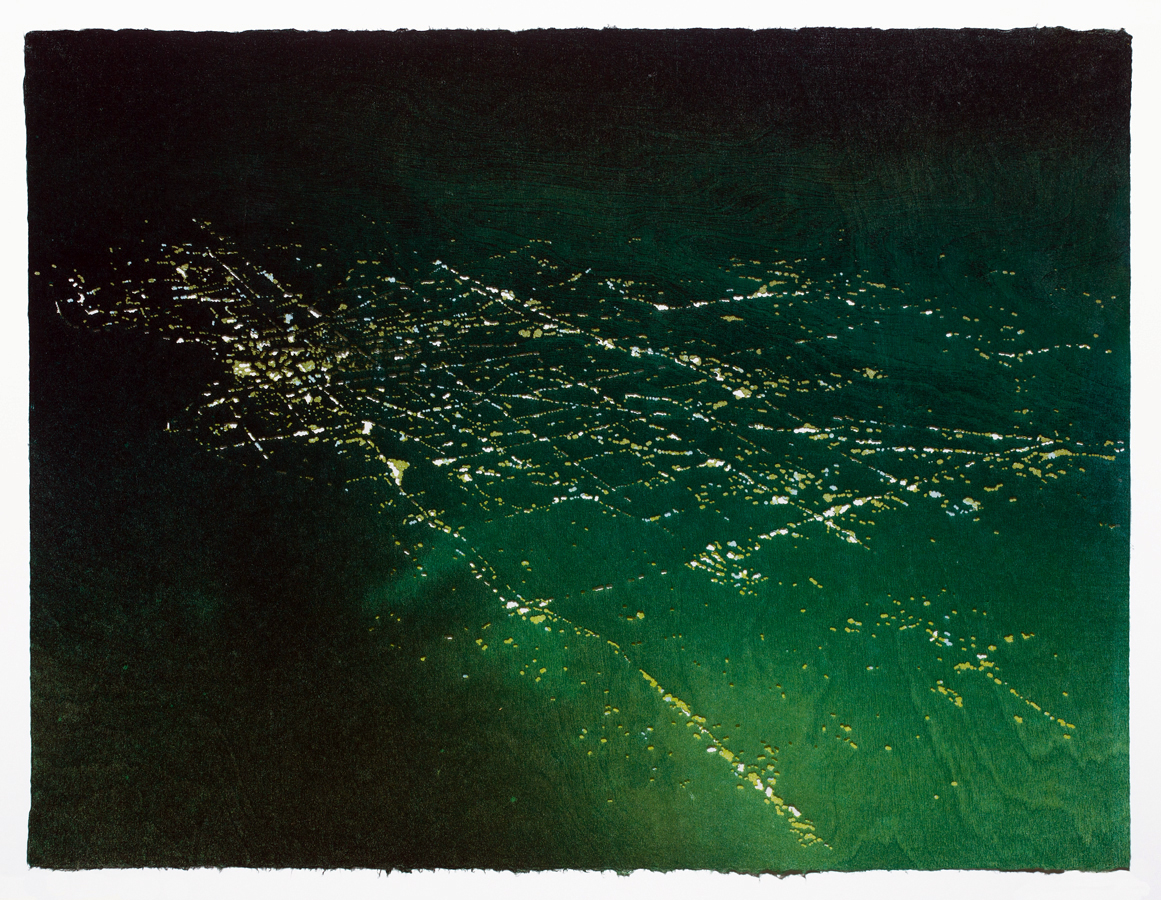

Installation image, Pescovitz Collection, OUAG, 2021

In general, collectors have little regard for investment or profit. Rather, art is important to them for other reasons. The best way to understand the underlying drive of art collecting is by describing it as a means to create and strengthen social bonds and for collectors to communicate information about themselves to the world and newly formed networks. Great collectors are often as well-known and widely respected as the art they collect.

Look at the Eli Broad collection, the Barnes collection or the Paul Allen collection, just to name a few. Collectors like these are famous because they demonstrate talent in selecting their art. J. Paul Getty, an oil baron from Minnesota, started collecting European paintings right before the Second World War, and Peggy Guggenheim, the niece of Solomon R. Guggenheim, was an early 20th-century socialite who became one of the most famous art collectors in the 1930s and 1940s.

Dr. Ora Hirsch Pescovitz, President of Oakland University, and her husband Mark collected art for forty years before he passed away in 2010. What started out as a small collection by her husband in the early 1970s evolved into a lifetime commitment.

The exhibition opened September 10, 2021, at the Oakland University Art Gallery, and is curated by Dick Goody, Chair, Department of Art & Art History and Director, Oakland University Art Gallery.

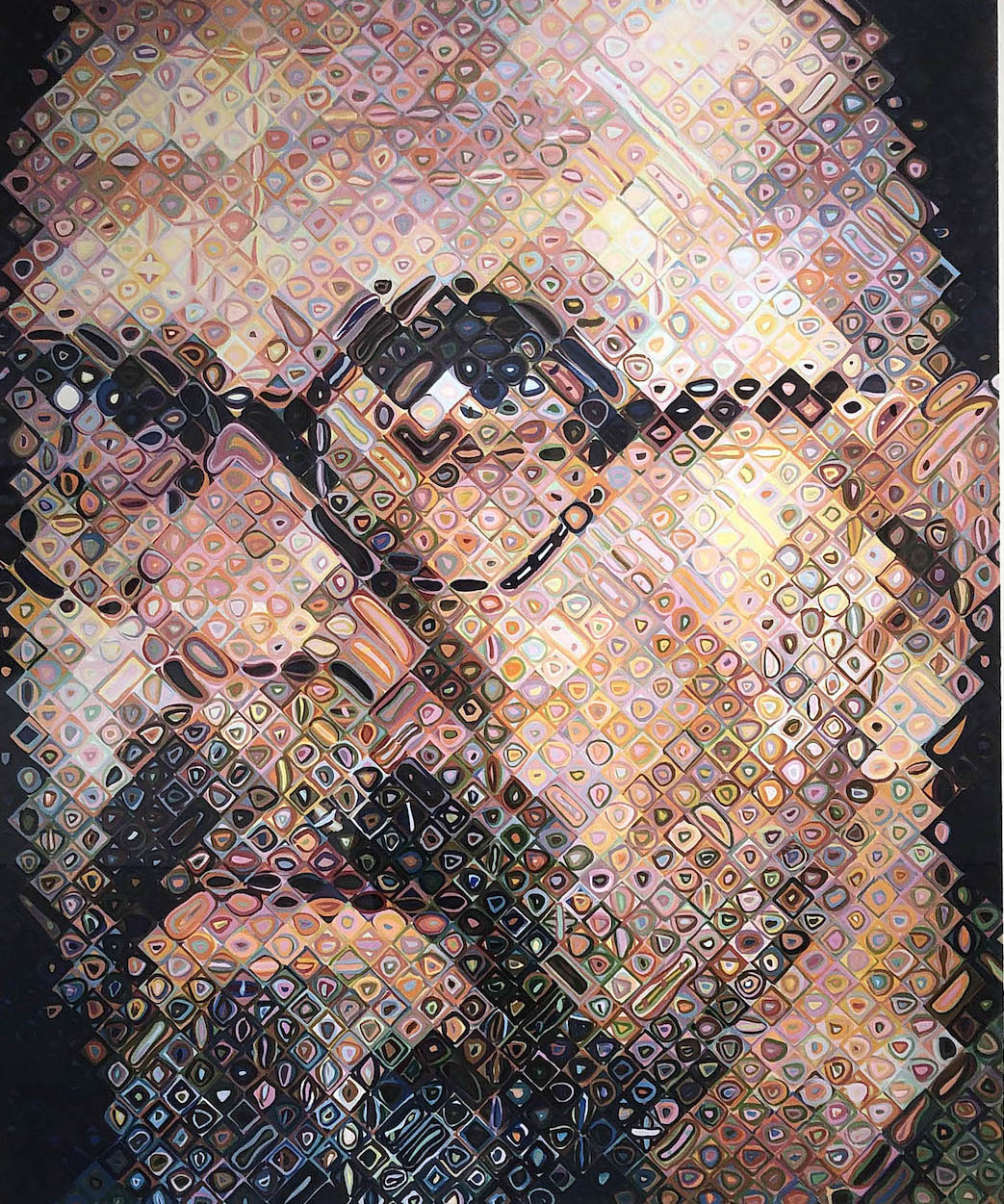

Chuck Close, Self Portrait, Silkscreen on Paper, 2000

Chuck Close rose to attention in the early 1970s with his grid-based compositions that replicated a type of photographic realism. The basis for his work depends on a photo image made up of small colorful shapes but, when viewed at a distance, reveals the more significant intended subject, usually a person or portrait. It is the invention of these small shapes that sets the work apart. Close just recently passed away in August 2021. Chuck Close earned a BFA from the University of Washington and an MFA from Yale.

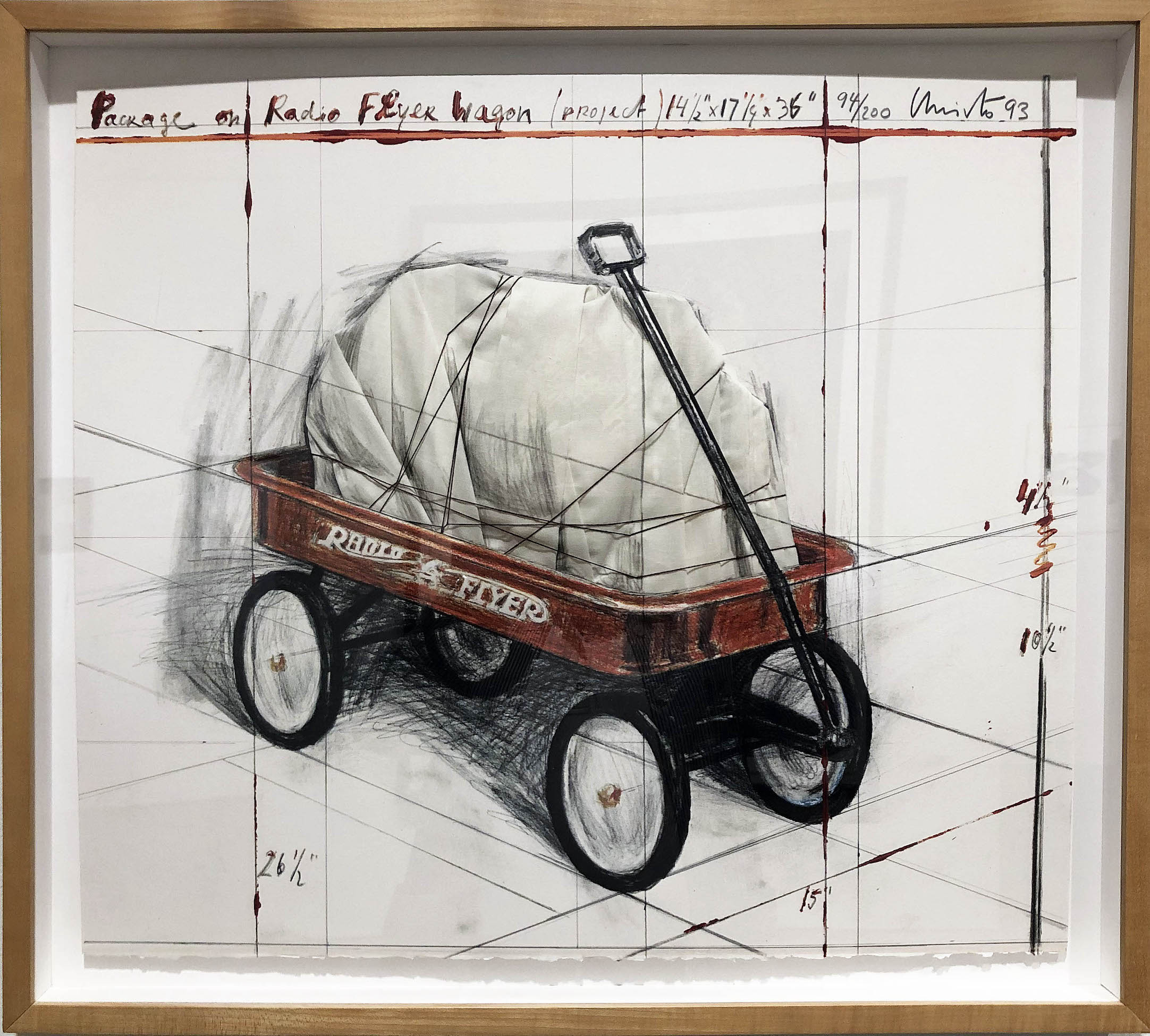

Christo & Jeanne-Claude, Package on Radio Flyer Wagon, 1993

Christo Vladimirov Javacheff and Jeanne-Claude were artists known for creating large-scale, site-specific environmental installations, often large landscape elements wrapped in fabric. Christo and his wife and artistic partner viewed their work as conceptual, as best seen in The Gates in Central Park, NYC, where visitors would pass underneath steel frames supporting free-standing panels of saffron-colored fabric. Much of their work was done preparing for an installation, supported with numerous drawings and prints. Radio Flyer Wagon, created in 1993, is a preliminary idea created using lithography and silkscreen printing. Christo passed away on May 31, 2020, in New York, NY. Their works are held in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art collections, the Musée d’art moderne et d’art Contemporain in Nice, and the Cleveland Museum of Art, among many others.

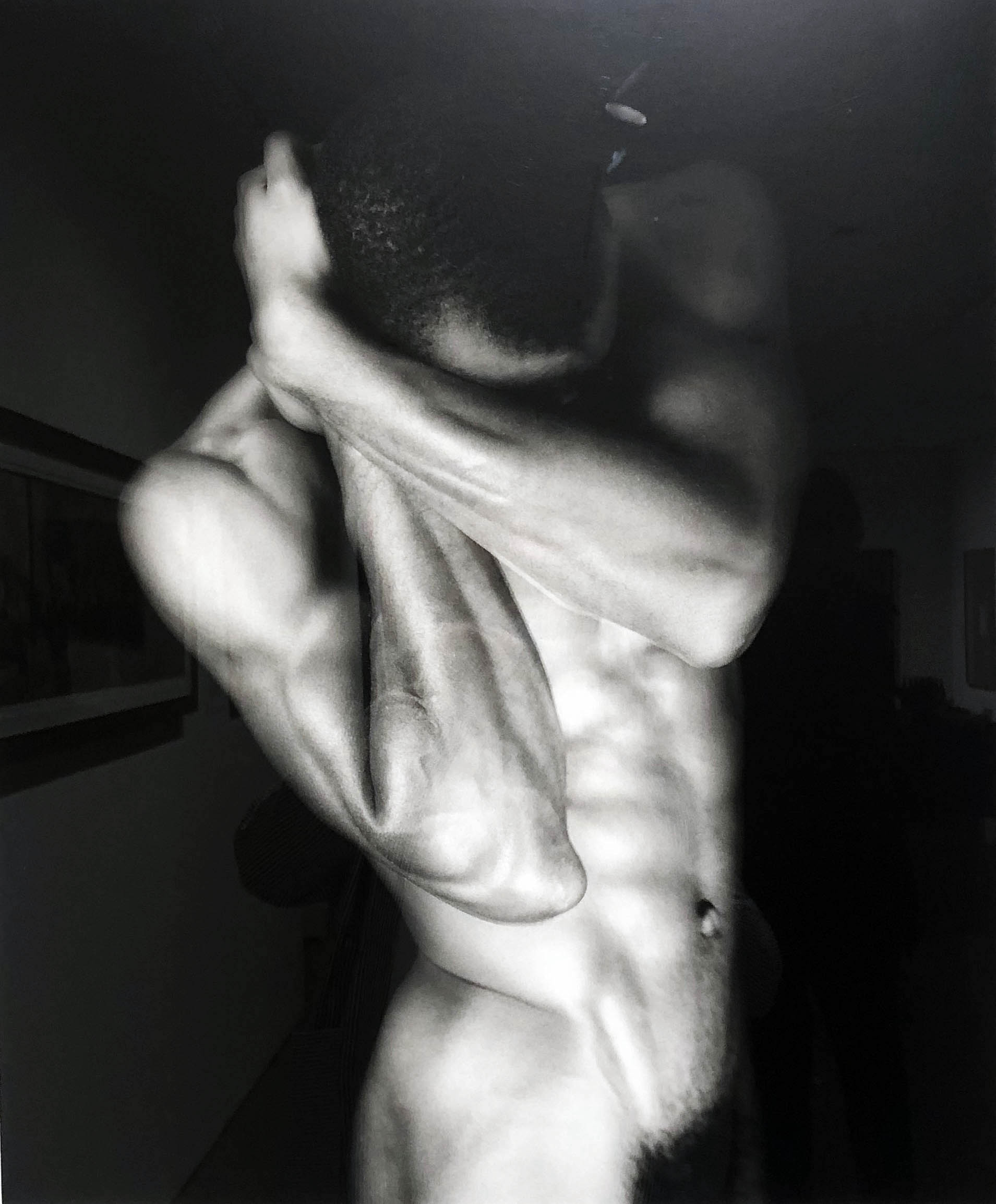

Robert Mapplethorpe, Thomas, Silver Gelatin Print, 1986

Robert Mapplethorpe was an American photographer, best known for his black and white images. His work featured various subjects, including celebrity portraits, male and female nudes, self-portraits, and still-life images. His most controversial works documented and examined the gay male BDSM subculture of New York City in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Mapplethorpe lived with musician Patti Smith in his early years. She says, “Robert took areas of dark human consent and made them into art. He was presenting something new, something not seen or explored as he saw and explored it. Robert sought to elevate aspects of male experience, to imbue homosexuality with mysticism.” The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation maintains and manages his work which raises millions of dollars for medical research.

Peter Milton, Family Reunion, Etching & Sugar Lift, 1986

Peter Winslow Milton is a colorblind American artist diagnosed with deuteranopia after hearing a comment about the pink in his landscapes. He attended the Virginia Military Institute and earned his MFA in 1961. Milton is a visual artist of black and white etchings and engravings that often display an extraordinary degree of photo-realistic detail placed in the service of a visionary aesthetic. His themes include architecture, history, and memory, as he employs complex layers in the printmaking process. In the work Stolen Moments, the method of aquatint printmaking is used where the artist creates wash effects by brushing them on the printing plate with a fluid in which sugar has been dissolved. The plate is then covered with stopping-out varnish and immersed in water; the sugar swells and lifts the varnish off the plate. Peter Milton attended the Virginia Military Institute and earned his MFA in 1961.

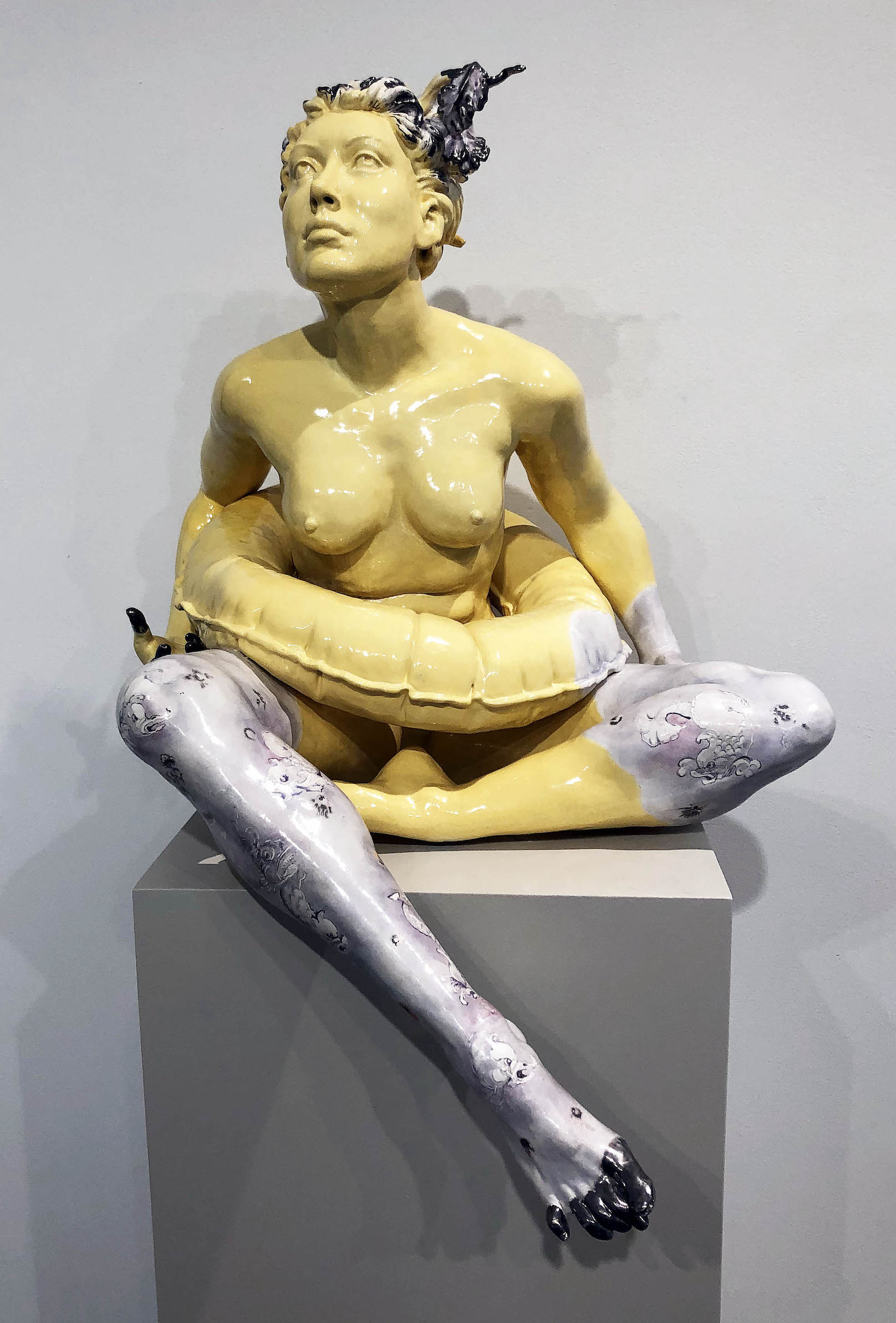

Christyl Boger, Off Shore, Glazed Earthenware, 2004

The artwork of Christyl Ann Boger is largely idealized nude ceramic figures that resemble 18th-century Greek porcelain sculpture with aspects that mimic contemporary ceramics. In her statement, she says, “ The pieces featuring figures posed with a variation on inflatable beach toys that reference the heroic narratives of Greco Roman mythology in an absurdist way.” The figures are 1/3 life-size earthenware, often incorporating gold enameling and typical western patterns such as fruits and flowers. She worked as a Professor at Indiana University and earned her BFA at Miami University and her MFA at Ohio University.

Phillip Campbell, Afternoon Escape, Acylic on Canvas, 1991

Philip Campbell creates paintings and objects that have a physicality about their presence. These are either assemblages or collages on canvas, and he works with wood, paper and cloth. Afternoon Escape’s abstracted landscape is an acrylic collage on paper with simplified shapes of colorful objects. He says in a statement, “By completing this major transformation, I have become a physical reflection of my art and a living product of my life’s work to date as well as inspiration for my future creations. A completely changed, renewed human being. My renewal experience has been the topic of many interesting conversations, and because of the discomfort of the healing process, I have been acutely and constantly aware of my transformation.” Philip Campbell earned his BFA from the Herron School of Art.

Installation image, Pescovitz Collection, OUAG. 2021

There’s a difference between buying art and collecting art. Buying art is more of a random activity based on likes, preferences or attractions at any given moment while collecting art is more of a purposeful, directed long-term commitment. The Pescovitz Art Collection on display at the Oakland University Art Gallery provides the students and the public with a large variety of artworks representing a diversity of art forms and expression. It is worth a visit.

This exhibition includes artworks by: Yaacov Agam, Philip H. Campbell, Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Chuck Close, James Wille Faust, Sam Gilliam, Janis Goodman, Robert Mapplethorpe, Peter Milton, Judy Pfaff and John Torreano.

Selections from the Mark and Ora Hirsch Pescovitz Collection, will run through November 21, 2021 at Oakland University Art Gallery.