Landlord Colors artists and curators: Left to Right: Elizabet Cervino, Reynier Leyva Novo, Laura Mott, Ryan Myers-Johnson, Billy Mark (in the back), Taylor Aldridge, Sterling Toles (in the back), Elizabeth Youngblood (in the front/cape), Susana Pilar, Cornelius Harris. Photo by Sarah Blanchette

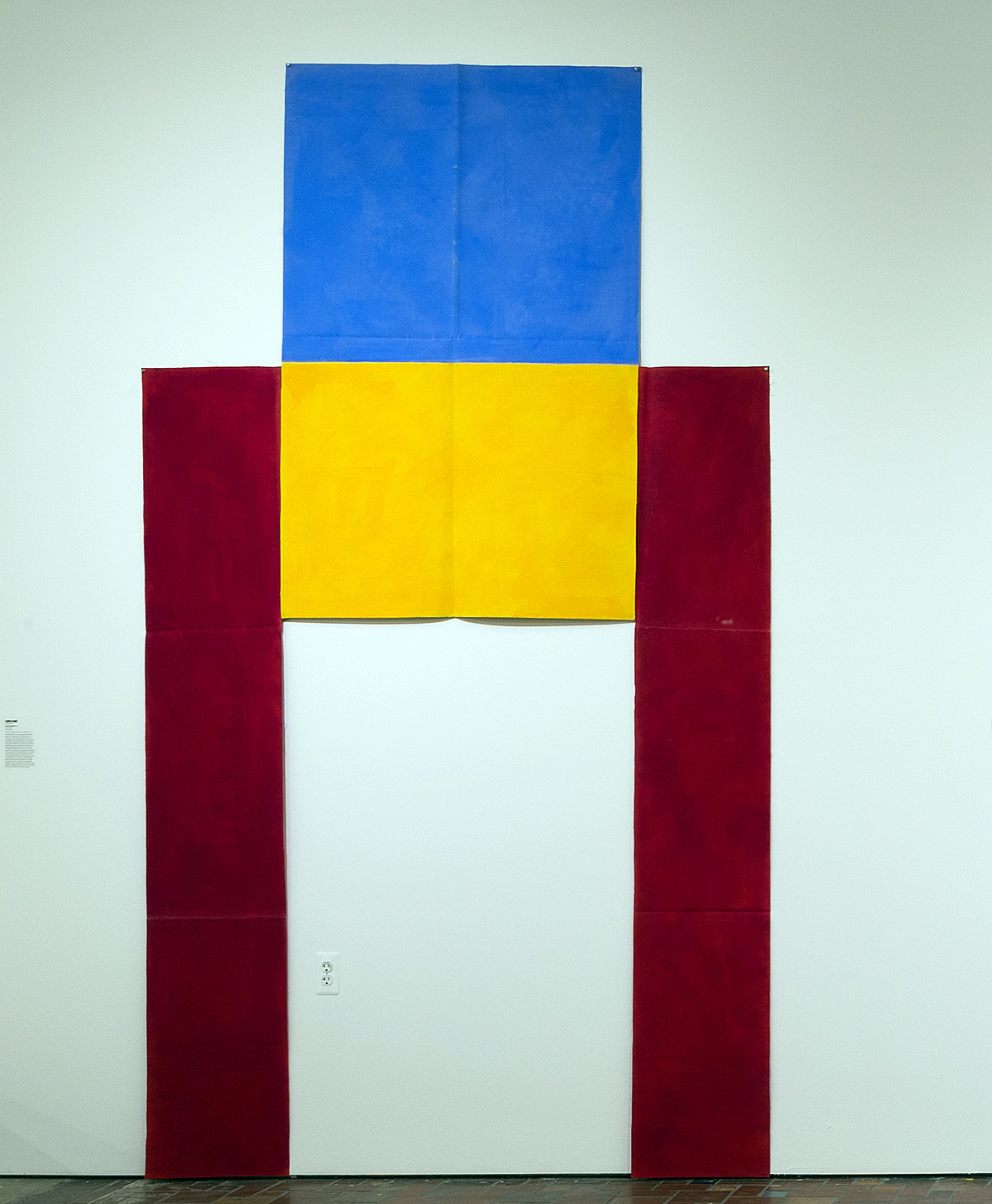

In “Landlord Colors,” Laura Mott, innovative Senior Curator of Contemporary Art and Design of the Cranbrook Museum of Art, has assembled an ambitious project that takes a look at not only some Detroit art since the 1967 “Uprising,” aka “Detroit Riots,” but situates Detroit’s art production in an international context of art scenes in similar political and economic straits. Focusing on four additional art moments– including Italy’s art provera movement of the 1960-80s; South Korea’s Dansaekhwa painting movement; Cuban art post-Soviet Union collapse, and art in Greece’s after its 2009 economic crisis– with similar political and economic crisis, Mott has, with passionate commitment curated an intellectually engaging and thoroughly researched exhibition. Focusing on the materiality of artistic production, Mott, rather than through an aesthetic lens, has abided by the principle of seeing art as cultural documents and explored them accordingly. Thus, she sees the artist’s choice of artistic materials as a complex expression of sociopolitical dynamics. To echo Marshall McLuhan the material is the meaning.

Punctuating the Cranbrook Art Museum in seemingly random order, the installation is neither chronologically nor thematically arranged but rather it seems organized by visual impact. There are stunning works throughout the exhibition, that, while they invite comparison, regardless of context, are completely remarkable in their inventive use of unusual or unique materials. One almost need not heed the didactic panels that articulate Mott’s theme as it reveals itself in every work.

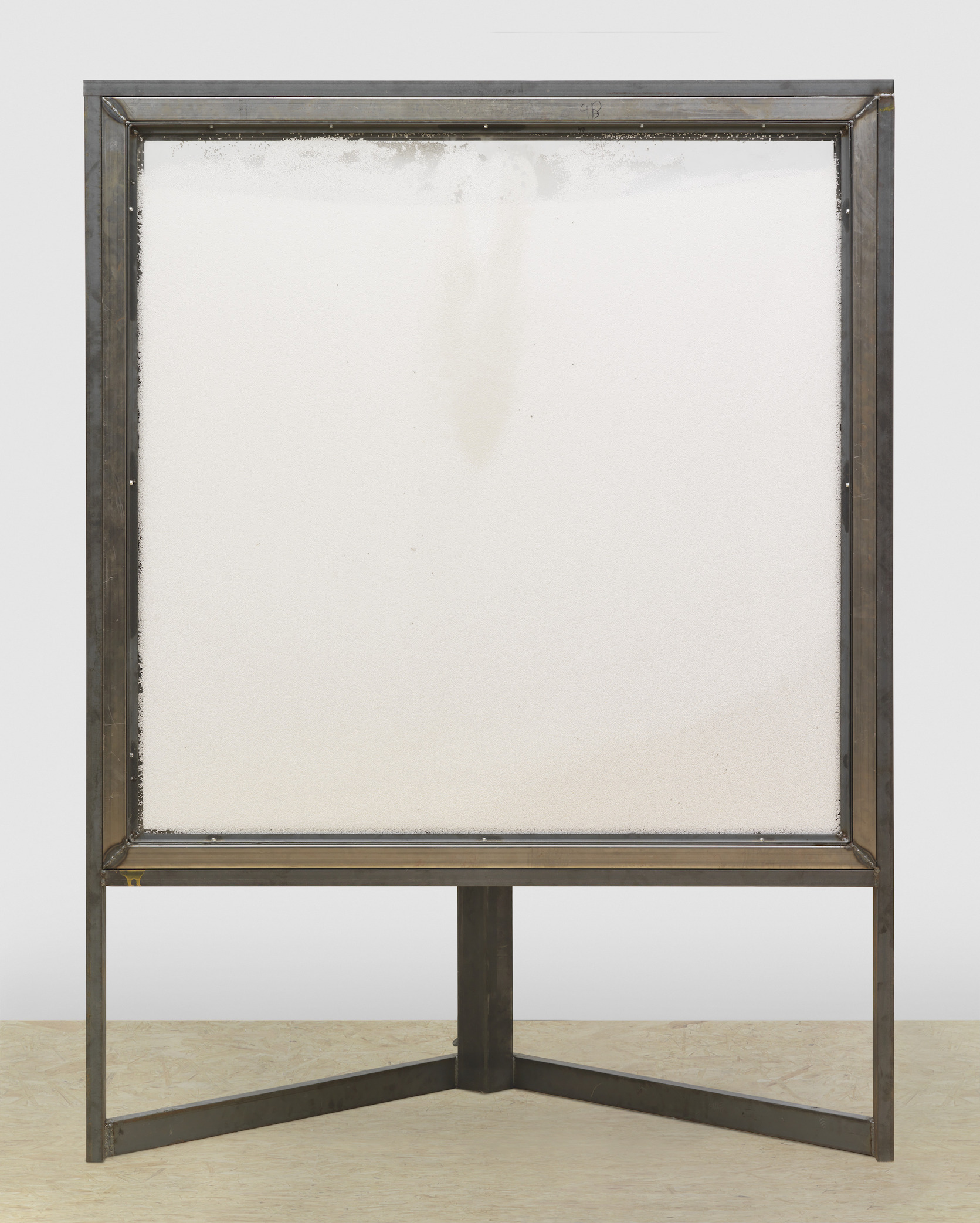

Gordon Newton, “Diamond Follow,”1975, 112” x 59” x 39,” Canvas, paint, polymer resin, synthetic fabric on wood. Photo by Julie Fracker

Almost as homage to Cass Corridor artist Gordon Newton who recently passed, the first object encountered at the entrance to the exhibit, is one of his large plywood abstract drawing/reliefs. “Diamond Follow” is composed of a plywood panel, one of the most rudimentary and readily available building materials, mounted on an easel and vigorously incised, cut, gouged, punctured with a circular saw and auto-body grinder and dabbed with paint and resin and collaged with canvas and fabric. Newton was singular in his aggressive manipulation and wrangling of just about any material into a platform for an expressive image. Back-in-the-day, a nightly visit to the Cass Corridor’s Bronx Bar was de rigueur where intense conversations about art and politics often took place. On one occasion Gordie, artist Jim Chatelain and poet Dennis Teichman were having a beer there and discussing art making and Gordie expressed with much force, “Anything goes, any material, just no stories, no telling stories!” By which I always thought he meant no narrative in visual art, only the intensely focused image, fraught with emotional information, whether abstraction or figure, regardless of material. Interestingly he avoided conversational storytelling as well and only seemed to be interested in explorational and energetic exchange. That interpretation seems to hold up in most of his work.

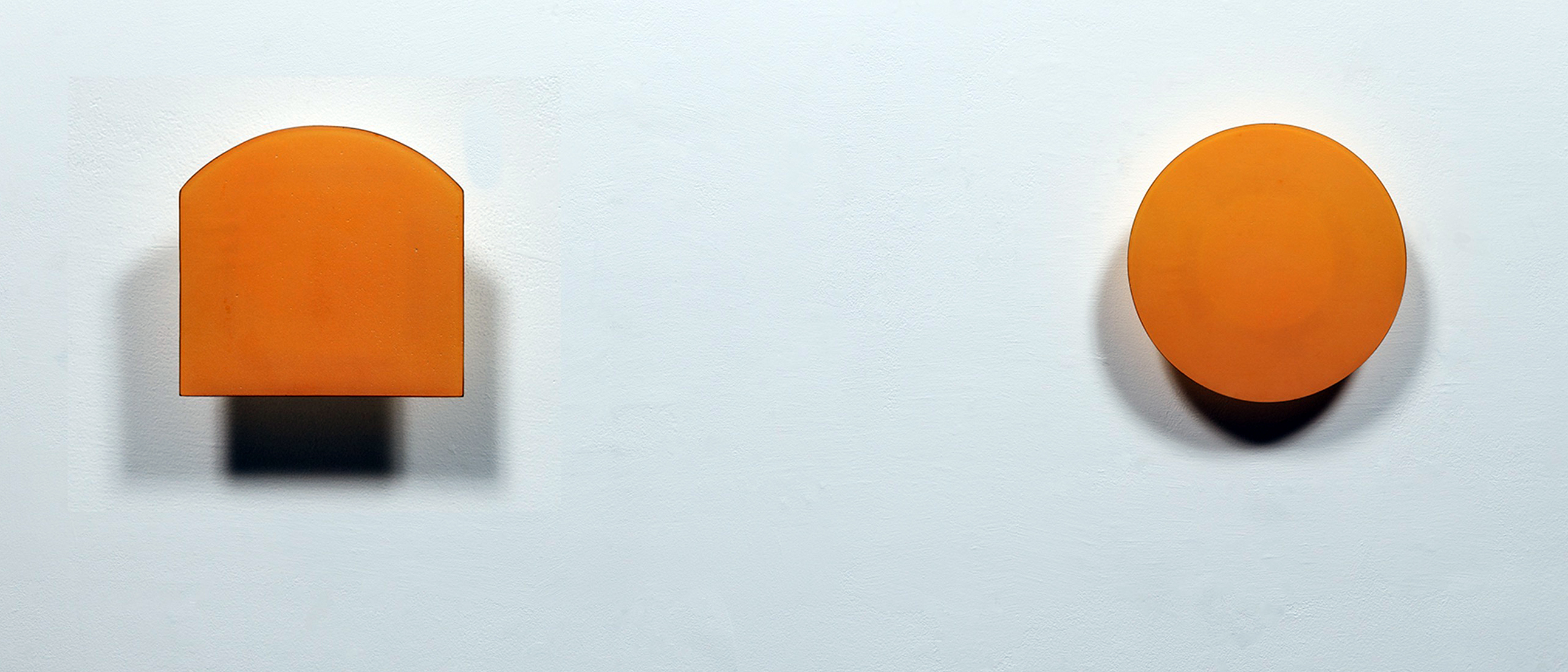

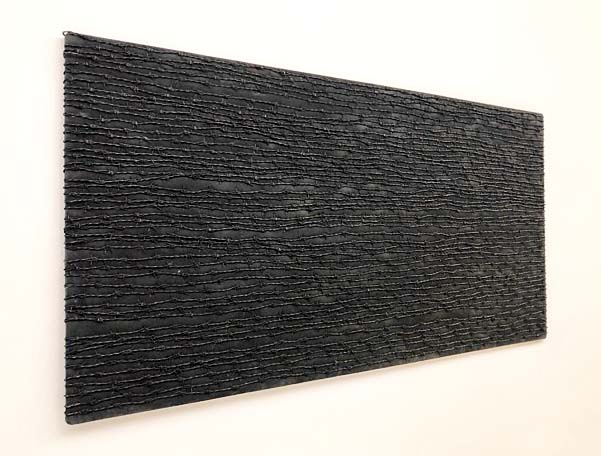

Hong Chong-Hyun,” Untitled 72-(A),” 1972, Barbed wire on panel, 45” x 94.5.” Photo by Julie Fracker

Equally edgy and dramatic is Korean artist, Ha Chong-Hyun’s, “Untitiled 72-(A)-1,” 1972, which sees rows of barbed wire stretched across a large, flat gray panel. Minimal in effect, it is an emotionally dark, flat field that expresses no exit from Korea’s war torn moment. Like Newton’s plywood, it thrives on an inventive and semiotic play on (the cruelty) of a simple material.

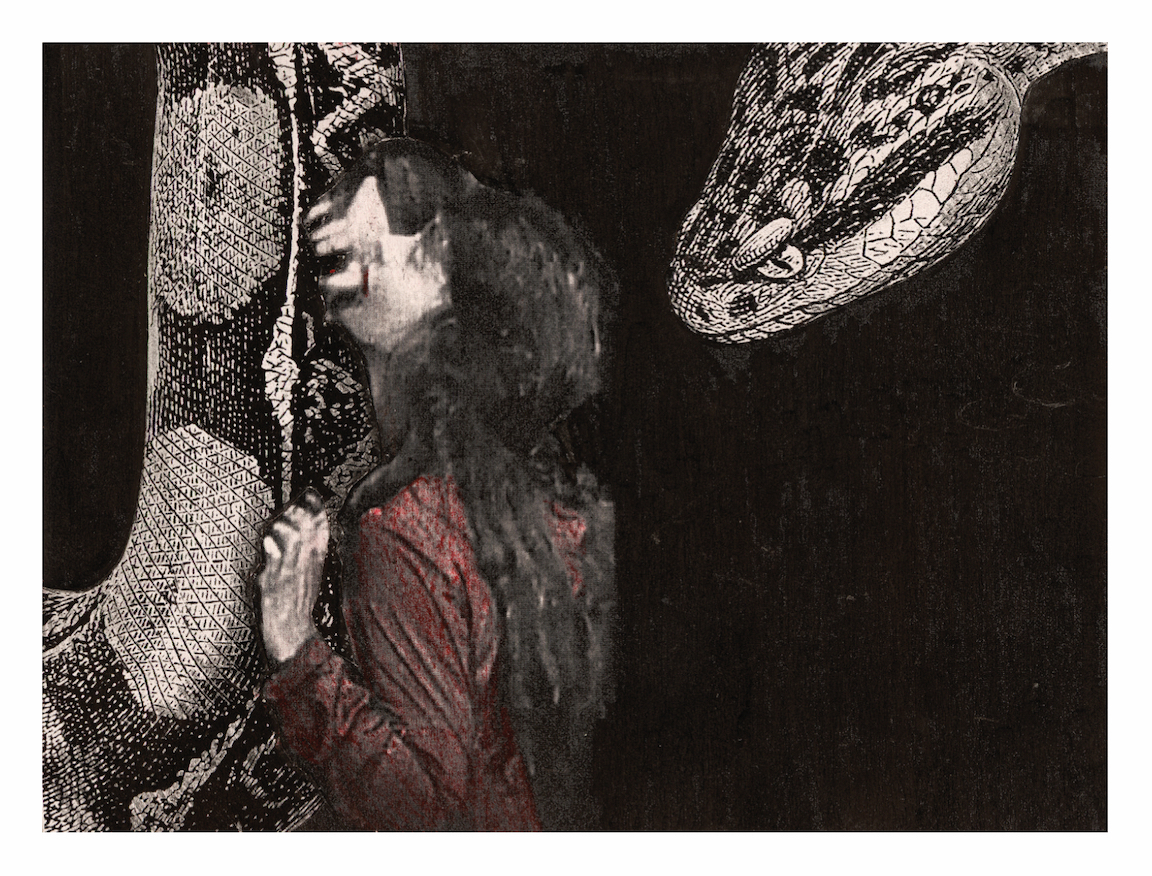

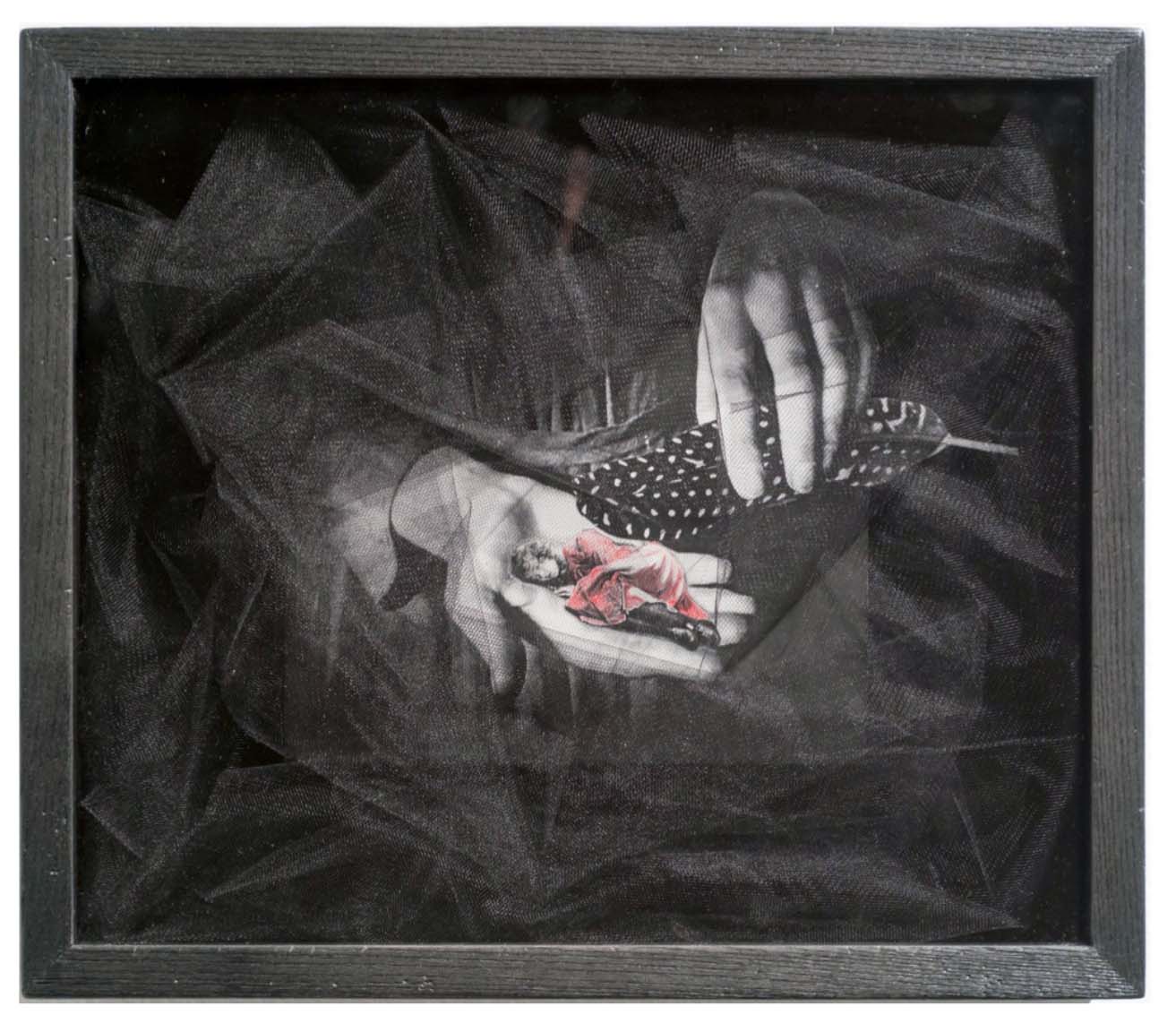

Two Cuban works express a similar political anxiety, both of which reference desire and peril of escape from oppressive social and political circumstances. Commissioned for Landlord Colors, Reynier Leyva Novo’s “Untitled (Immigrants), 2019, is a huge, colorful tapestry, 16’x16,’ woven of the clothing worn by Cuban immigrants, in Cuba by “paid workers,” during their passage to the United States. The epic rag seems at once celebratory of their escape to freedom and a memorial to the loss of their homeland. As material expression of their Cuban cultural homeland of which they were apart and lost, no material could be more expressive than the clothes off of their bodies.

Installation shot with Reynier Leyva Novo, “Untitled (immigrants),” 2019, clothing, 192”x 192” Commission for Landlord Colors Photo by Paul-David Rearick

Cuban artist Yoan Capote’s astonishing mixed media painting “Island (see-escape),” 2010, is 12’x 32,’ is composed of oil paint and some 500,000 large fishhooks that quite literally suggest the dangerous journey in attempting escape across the hundred miles of the Straits of Florida, from Cuba to the United States.

Yoan Capote, “Island (see-escape),” 2010, Oil, nails, fish hooks, on jute on panel,106” x 384” x 4” Photo by Paul-David Rearick

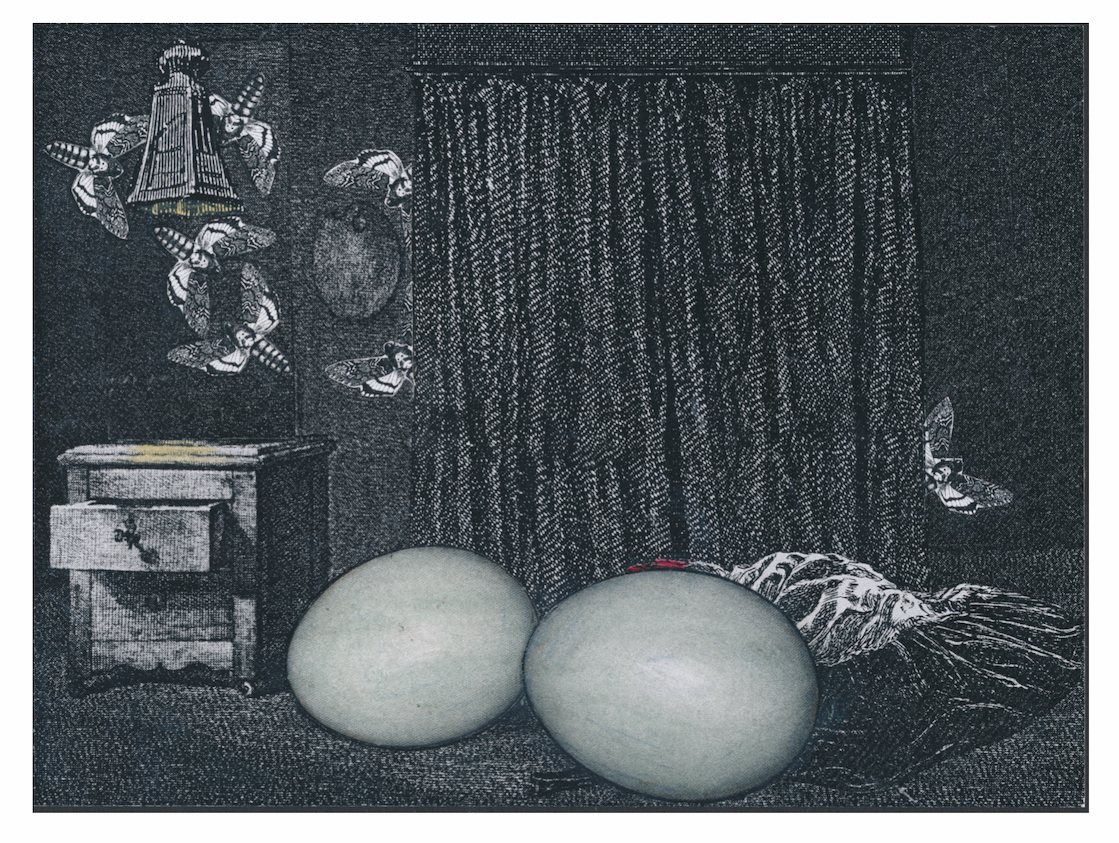

One of the most seemingly traditional works in Landlord Colors is Cuban artist Diana Fonseca Quinones’ painting “Untitled,” seemingly a classic abstraction of energetic splotches, almost like a topographical map, of paint that in fact are chips or flakes of paint collected from derelict buildings in Havana, Cuba. Laura Mott’s description of the painting in her own energetically, exhaustive monograph sees Quinones’s project as a “portrait of the Cuban psyche itself” as well as a “record over the years of economic trial.”

Diana Fonseca Quinones, “Untitled,” from the Degradation series, 2017, Paint fragments on wood, 47.244” x 47.244.” Photo by Julie Fracker

There are sixty works spread across the museum floors and walls that explore the diversity of, mostly, non-traditional art materials, each with its own resultant form of reflection of troubled times. But Motts curatorial intervention went further and the day after the opening, a series of installations and performances, entitled “Material Detroit,” commenced: starting with Detroit poet Billy Mark’s surreal performance/installation of the raising up a flagpole of a symbolic Hoodie with twenty-five foot arms. Audience participation allowed for audience members to wear the hoodie as its arms were raised, like a parody of a military ritual, and were invited to talk about the emotional experience of wearing this emancipating hoodie. The performance will become a ritual celebration of healing and empowerment in Mark’s North end neighborhood as it will be performed daily for thirty-seven days.

Billy Marks, “Wind Participation Ritual,” (Hoodie performance), 858 Blaine Street, Unidentified participant and Billy Marks. Photo by Glen Mannisto

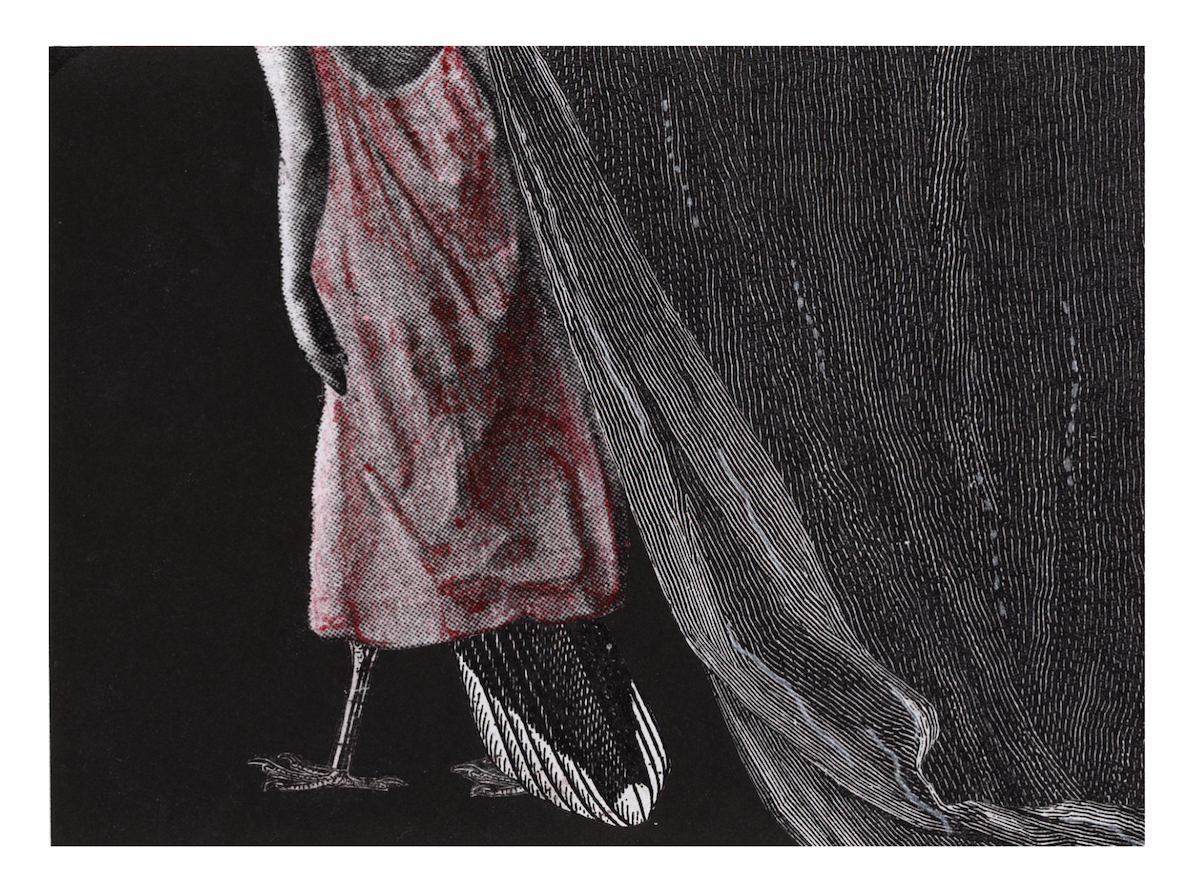

In the afternoon Havana-based, Afro-Cuban artist, and celebrated feminist, Susana Pilar, led a group of Detroit musicians in a magical performance at the site of the infamous Algiers Motel, 8301 Woodward Avenue, where multiple murders, with Detroit Police accusations, occurred and where the R&B group The Dramatics (“Me and Mrs. Jones”) were staying-out the Detroit uprising that night. Ceramicist and installation artist’s Anders Ruhwald’s “immersive” installation in “Unit 1: 3583 Dubois,” a charred black multi-room apartment with iconic anthropomorphic ceramic forms haunting the darkness, conjuring ghettoized nightmares was on the agenda.

The afternoon featured a visit to Olayami Dabls’ ever growing, Phoenix-like installations that adorn a building and surrounding lots on Grand River Avenue. Composed of a magnificent series of African inspired collaged murals, ceramic and mirror mosaics that celebrate Detroit’s African-American heritage, Dabl’s 19 installations, entitiled “Iron Teaching Rocks How to Rust,” is quite simply a Detroit treasure. Dabls’ project probably illustrates the curatorial theme of artist’s material resourcefulness and invention as well as any of the artists in the entire exhibition. The inscrutable Elizabeth Youngblood, inaugurates Dabl’s new gallery space with a mercurial painting from her new series of metallic paint on mylar and paper, two textile hangings, a geometric abstract painting and a series of small black ceramic vessels. Letting the molten-like metallic paint find its sensuous resting form and the blackened clay its universal metaphoric being is Youngblood’s deft handed genius.

The day ended with a visit to still-one-more brilliant epic installation, “Bone black,” by Scott Hocking of a metaphorically messianic vision of abandoned boats, rescued by Hocking (an ongoing theme in Hocking’s work), ethereally floating in an abandoned crane warehouse on the Detroit River front.

Scott Hocking, “Bone Black,” Installation image at former Detroit crane factory with Elizabeth Youngblood, 2019. Photo by Glen Mannisto

Laura Mott, and co-curators Taylor Renee Aldridge and Ryan Myers-Johnson’s project is over-the-top outrageously, assertively and critically engaged in its obsession with Detroit’s and our fragile global history. There is a continuing schedule of amazing events into the Fall including: Kresge grant winning, hip-hop artist Sterling Toles will occupy Gordon Park (where the Detroit uprising started) in Detroit in a performance of his “Resurget Cinerbus,” a sound work based on Detroit’s Rebellion. Curator Taylor Renee Aldridge will lead a series of Discussions. Check out the website for a list of other Fall events.

From painting to sculpture to installations the Landlord Colors makes inescapable the palpable relationship between art and sociopolitical conditions and ultimately as political action. Laura Mott’s startling curatorial intervention has profound implications in further negotiations of art history. Not only did the uprising of Detroit’s black citizens against a calculous of racism create a pall of pain over the city but shows, as do all of the five sites she explored, that art in fact springs from the isolated provinces of the local and defines the global condition.

An exhaustive and beautifully produced exhibition catalogue, Landlord Colors: On Art, Economy, and Materiality, written by Laura Mott with essays and interviews by artists and curators accompanies the exhibition.

Artists in the exhibition:

Italy) Giovanni Anselmo, Pier Paolo Calzolari, Riccardo Dalisi, Lucio Fontana, Jannis Kounellis, Maria Lai, Mario Merz, Marisa Merz, Giulio Paolini, Michelangelo Pistoletto (Korea) Ha Chong-Hyun, Kwon Young-Woo, Lee Ufan, Park Hyun-Ki, Park Seo-Bo, Yun Hyong-Keun (Cuba) Belkis Ayón, Tania Bruguera, Yoan Capote, Elizabet Cerviño, Julio Llópiz-Casal, Reynier Leyva Novo, Eduardo Ponjuán, Wilfredo Prieto, Diana Fonseca Quiñones, Ezequiel O. Suárez; (Greece) Andreas Angelidakis, Dora Economou, Andreas Lolis, Panos Papadopoulos, Zoë Paul, Socratis Socratous, Kostis Velonis; (Detroit, USA) Cay Bahnmiller, Kevin Beasley, James Lee Byars, Olayami Dabls, Brenda Goodman, Tyree Guyton, Carole Harris, Matthew Angelo Harrison, Patrick Hill, Scott Hocking, Addie Langford, Kylie Lockwood, Alvin Loving, Michael Luchs, Tiff Massey, Charles McGee, Allie McGhee, Jason Murphy, Gordon Newton, Chris Schanck, and Gilda Snowden.

Artists in “Material Detroit”:

(Installations) Dabls’ MBAD African Bead Museum, Jennifer Harge, Scott Hocking, Billy Mark, Anders Ruhwald, The Fringe Society, Elizabeth Youngblood. (Performances/Events) Big Red Wall Dance Company, Susana Pilar, Michelangelo Pistoletto (Third Paradise performance and a Detroit Rebirth Forum), Sterling Toles. The project culminates with the Landlord Colors Symposium at Cranbrook Art Museum in the fall.

Landlord Colors: On Art, Economy, and Materiality – June 22-October 6, 2019

Cranbrook Art Museum 39221 Woodward Avenue, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan