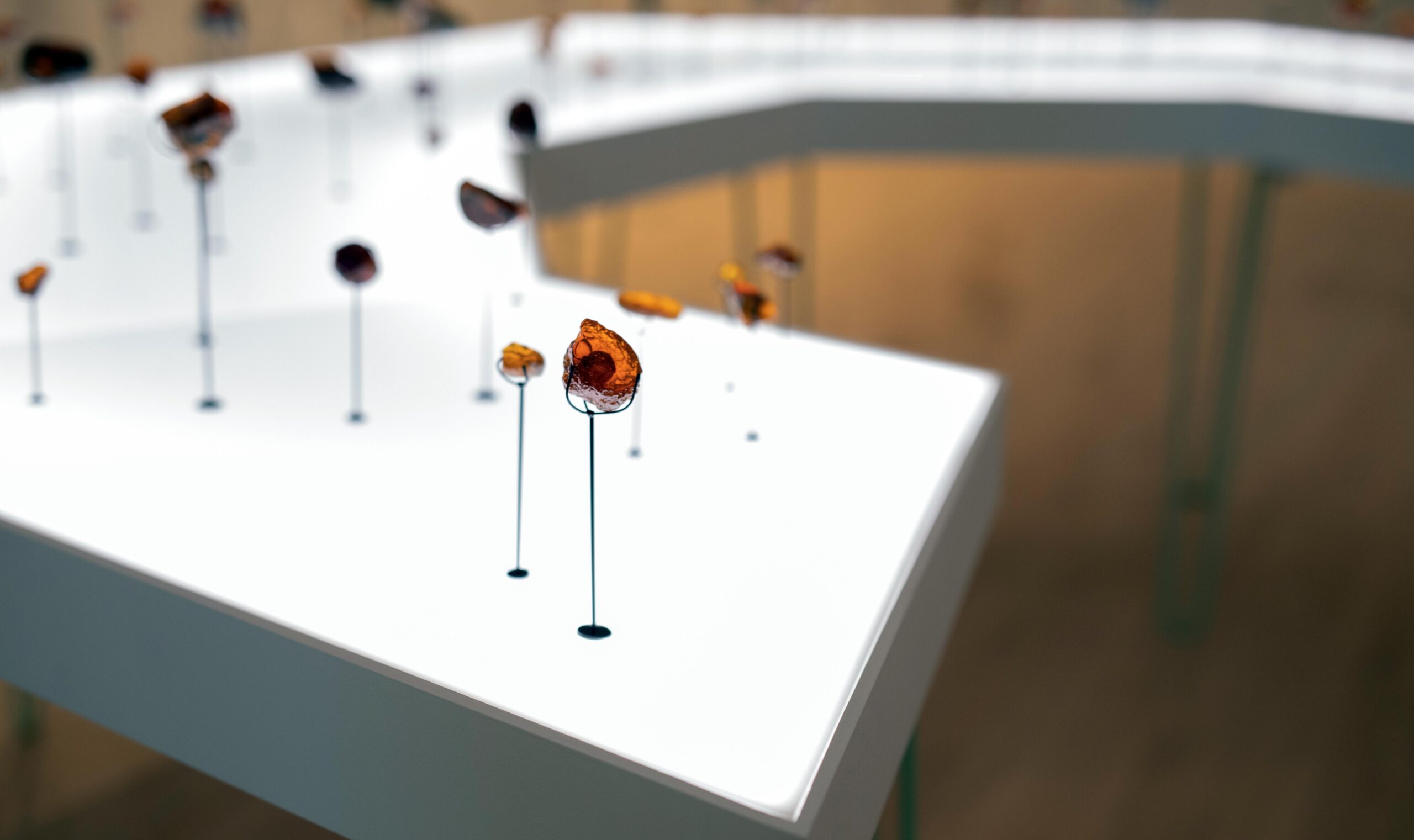

Cranbrook Museum of Art, With Eyes Opened, Sculpture Court and Mixing Chamber, installation, photo: PD Rearick

With Eyes Opened: Cranbrook Academy of Art since 1932 has just opened at the Cranbrook Museum of Art in Bloomfield Hills, to great acclaim and national attention. Covered by the New York Times Magazine with a spiffy video tour and ample media attention both local and national, it’s a hydra-headed beast of a show with many sponsors but no single curator. Objects and images from every period of the Academy’s history compete for space and attention, with no fewer than ten dueling accounts threaded throughout the museum’s seven galleries.

The organizers seem to have had difficulty settling on a single narrative for this exhaustive survey of the Academy’s history–and no wonder. The tapestries, sculptures, paintings, prints, photographs, product prototypes and mass-produced products tell a kaleidoscopic story of the many creative minds whose vision and creativity have emanated from the school over time.

The history of this premier American art institution is told through objects in only piecemeal fashion in the physical exhibit; the accompanying printed volume, a 624-page doorstop of a book, contains a more complete narrative of the school’s history, along with one-page profiles of many (though not all) of the artists and designers represented in the show.

Untitled (Aluchair) by Christopher Schanck (MFA, 3D Design 2011), 2019, aluminum foil, resin Collection Cranbrook Art Museum

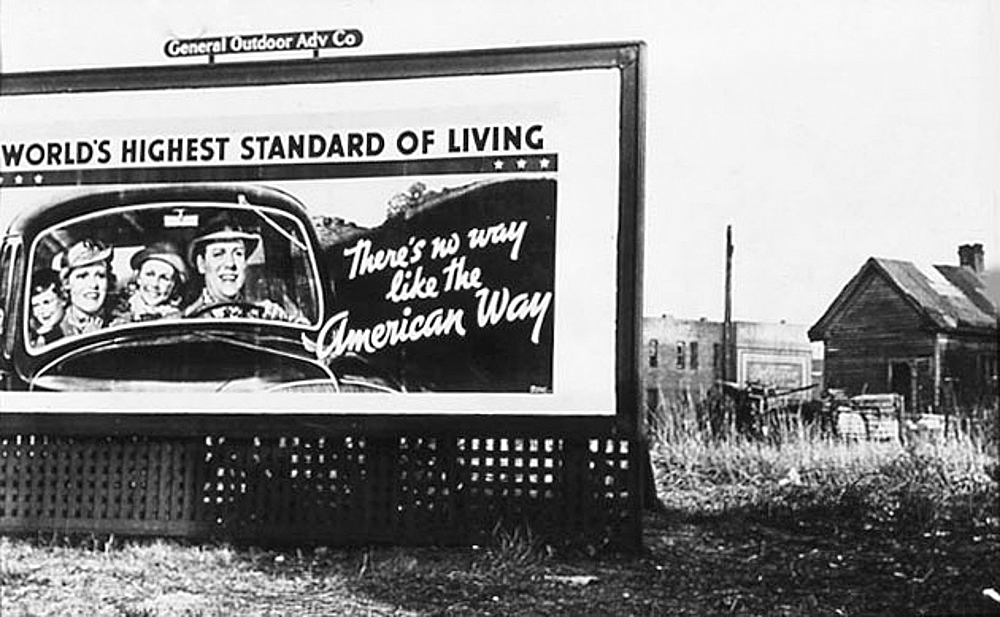

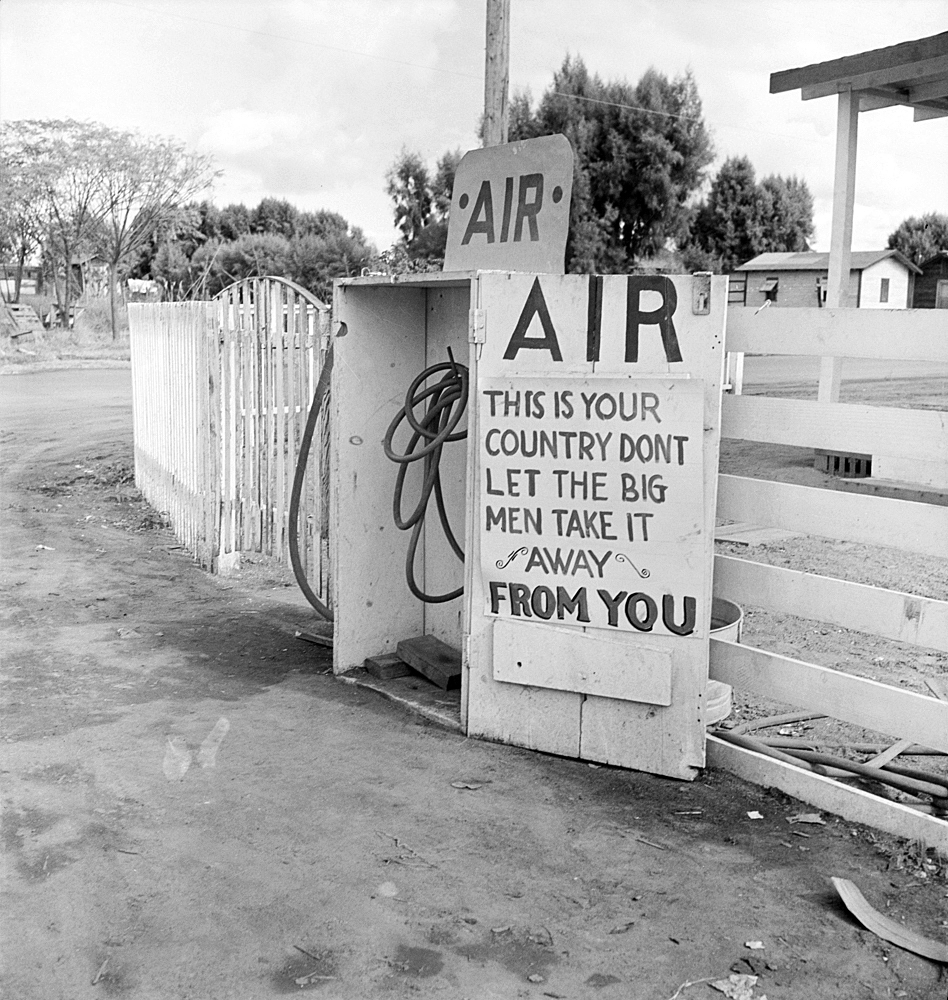

At the entrance to the main gallery, visitors can watch American Look. Commissioned in 1958 by Chevrolet, this cold war artifact celebrates many of the post-World War II designed amenities that were newly available to middle class consumers of a certain limited demographic. Throughout the celebratory video, the “American-ness” of the consumer lifestyle is promoted relentlessly. Even though the uncritical materialism may seem cringe-worthy to a modern viewer, the optimism and can-do mentality expressed in the video amply show why the period beginning in 1950 is often called the American Century. The film provides a good starting point for With Eyes Opened, which takes us on a visual tour not only of the mid-century American esthetic, but also, by implication, through a consideration of how those perceptions and values have grown and changed over time to include contemporary preoccupations with equity, diversity and sustainability.

Model 1601 Stacking Chair by Don Albinson (Cranbrook Academy of Art Sculpture, 1940-1941), 1965, aluminum, nylon, molded plastic. Photo PD Rearick

The video serves as an introduction to one of the more successful elements of the exhibit, which celebrates the modern chair. Designers like Charles and Ray Kaiser Eames and Don Albinson were uniquely successful at conceptualizing and producing practical, relatively inexpensive and attractive mass production chairs, many instantly recognizable today as fixtures of modern life in home and office. The chair as a concept unifies this display; in addition to the mass produced chairs there are a number of hand-crafted, one-of-a-kind examples such as Chris Schank’s Alufoil Chair and Terence Main’s Queen Anne, Queen Anne doubled chair. Here, as throughout the exhibit, the organizers have decided to mix the mass-produced and the hand-crafted, without comparing or contrasting the purposes and philosophies involved.

Cranbrook Museum of Art, Sculpture Court, installation. Photo: DAR

The physical and esthetic center of the exhibition, which brings the concept of design and art to a satisfying apotheosis of the handmade and the mass-produced, comes in the Mixing Chamber. There, the room-sized mural of black and white figures by Cleon Peterson suggests the sensibility of a 21st century Egon Schiele. Tortured, semi-nude bodies surround the wittily conceived bench by Vivian Beer, whose automotive-painted red drape on the slipper shape is at once modern and baroque.

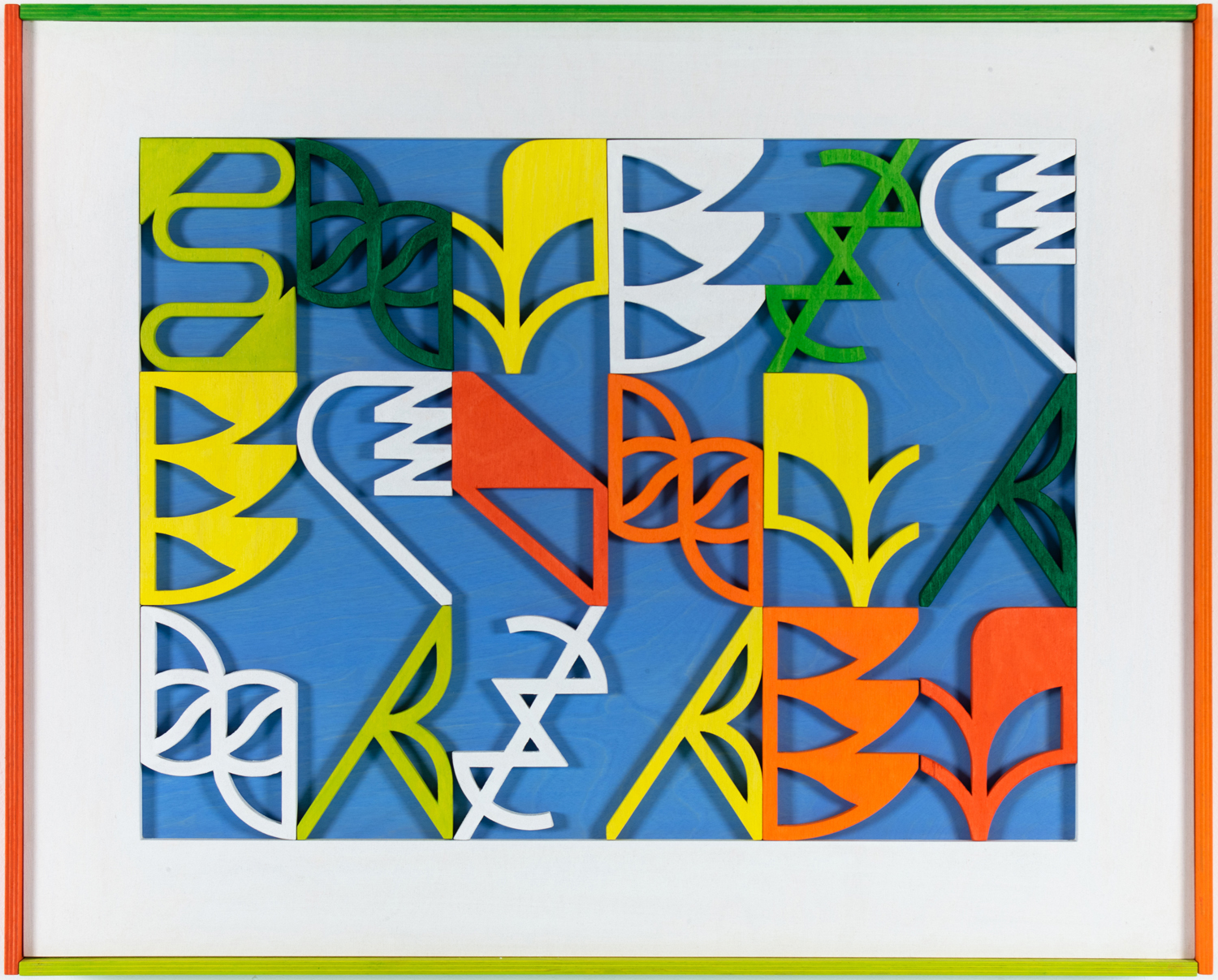

Untitled (Asthma, High Blood Pressure) by Beverly Fishman (Artist-in-Residence, Dept. of Painting 1992-2019) 2018, urethane paint on wood. Photo: PD Rearick

In the adjacent North Gallery, 34 paintings, works on paper and photographs hang floor to ceiling, with abstraction as the ostensible unifying theme. The hanging of contemporary art salon style is a fraught strategy that calls for sensitively selected and carefully coordinated curation and enough space around each piece to allow the work to breathe. Here the disparate artworks compete visually, like guests at a crowded cocktail party shouting to be heard. Beverly Fishman’s brightly colored, sharp-edged geometric polygons (almost) hold their own, and McArthur Binion manages to succeed simply by installing a painting, DNA: Study (Lake St. Clair), too large to share the space with other artwork. As worthy as each piece in the gallery may be, a little editing would have been welcome.

Untitled by Rebecca Ripple (Artist-in-Residence, Dept. of Sculpture, 2017-present) 2016, plastic, aluminum brass, photocopy, pencil, hair, champagne foil. Photo: K.A. Letts

In the Sculpture Court, through the Mixing Chamber ‘s other doorway, Nick Cave’s exuberant SoundSuit (2012) holds the floor, with a recessive companion, Flamer, by Mark Newport, hanging on the adjacent wall. Duane Hanson’s provocatively banal figure lounges nearby, unimpressed. Other strong work in the sculpture court includes several fiber pieces which seem to have wandered in, perhaps to provide space between the large and diverse 3-dimensional works–not a bad idea as it turns out. The white-on-white tapestry Montana 30, by Colombian artist Olga de Amaral, made up of small squares of white painted canvas relieved with touches of red, is especially welcome here. Sculptures by artists of the past such as Marshall Fredericks and Carl Milles share the space, more or less peacefully, with artworks by younger artists like Tyanna Buie and Kate Clark. Toward the back of the gallery, James Surl’s spiky mobile floats in its own private galaxy, next to a terrific assemblage by Rebecca Ripple that radiates an ad hoc starburst of Miro-esque energy.

Auburndale Site, Detroit MI (#4) by Object Orange, 2006, archival color photograph, 1/25 Cranbrook Museum of Art. Photo: K.A. Letts

In a small side gallery near the elevators, three photographs by the art collective Object Orange deliver a moment of surreal surprise. From 2005-2007, these (anonymous) Cranbrook graduates undertook a conceptual project called Detroit, Demolition, Disneyland which involved painting–in “Tiggerific” Orange– derelict structures in the city as a form of both public performance and protest. The photographs, brilliant orange structures against bleak gray backgrounds, are arresting, unexpected and a bit melancholy.

Cranbrook Museum of Art, With Eyes Opened, Object Islands, installation, Photo: PD Rearick

The Wainger Gallery, last stop on the main floor galleries, features a clever installation of “object islands,” table height circular plinths that subtly guide the viewer through a broad array of fairly small- scale ceramics, metal objects and product design prototypes. Many of the objects in this gallery are one-of-a-kind art objects in a variety of media, often in unusual combinations, such as Iris Eichenberg’s untitled brooch made of porcelain, silver and linen.

With Eyes Opened takes on a lighter tone in the museum’s lower level gallery with The Menagerie, a whimsical collection of figures and objects inspired by the natural world, from Marshall Frederick’s chunky Two Bears to Stephen Malinowski’s photograph Cafeteria, a surreal bison-in-a-dining room. The playful theme of The Menagerie is echoed nearby with a small collection of toy and playground designs that, while welcome, seem like an afterthought.

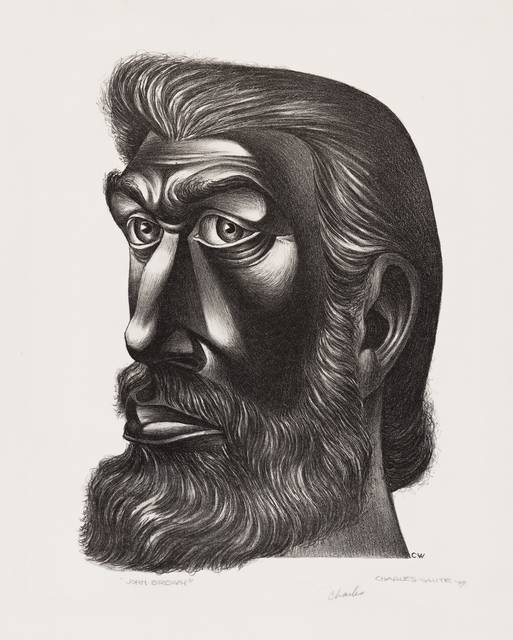

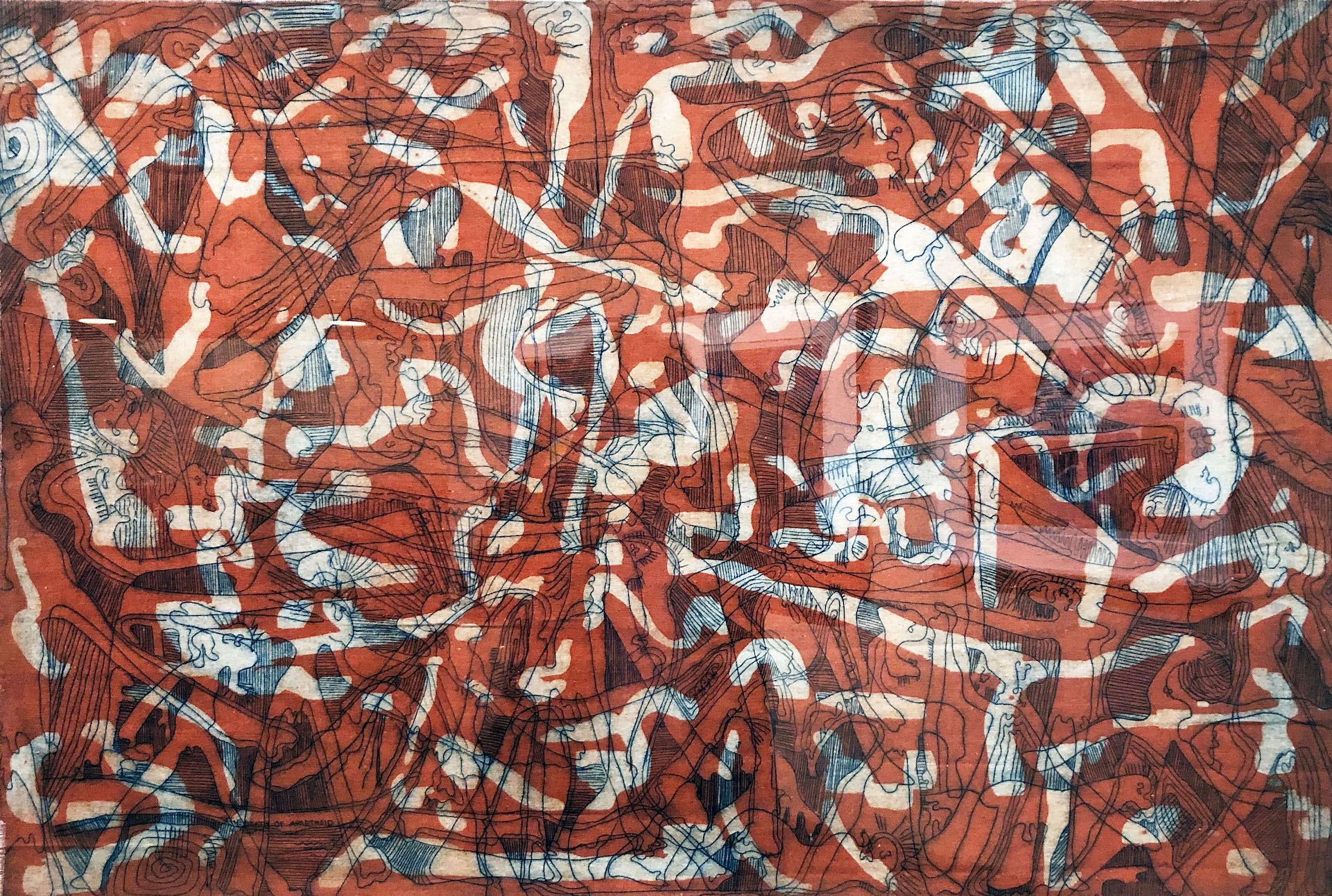

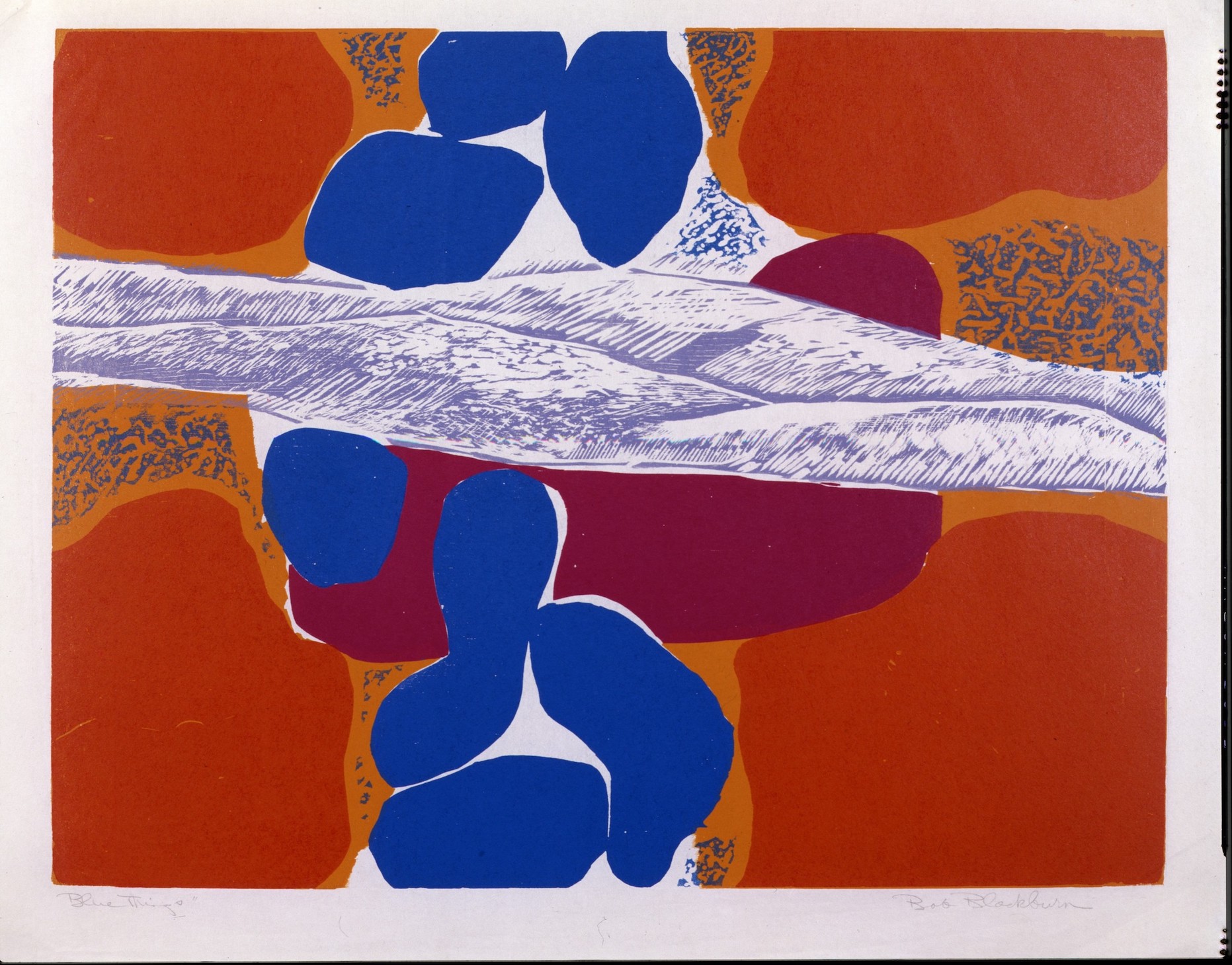

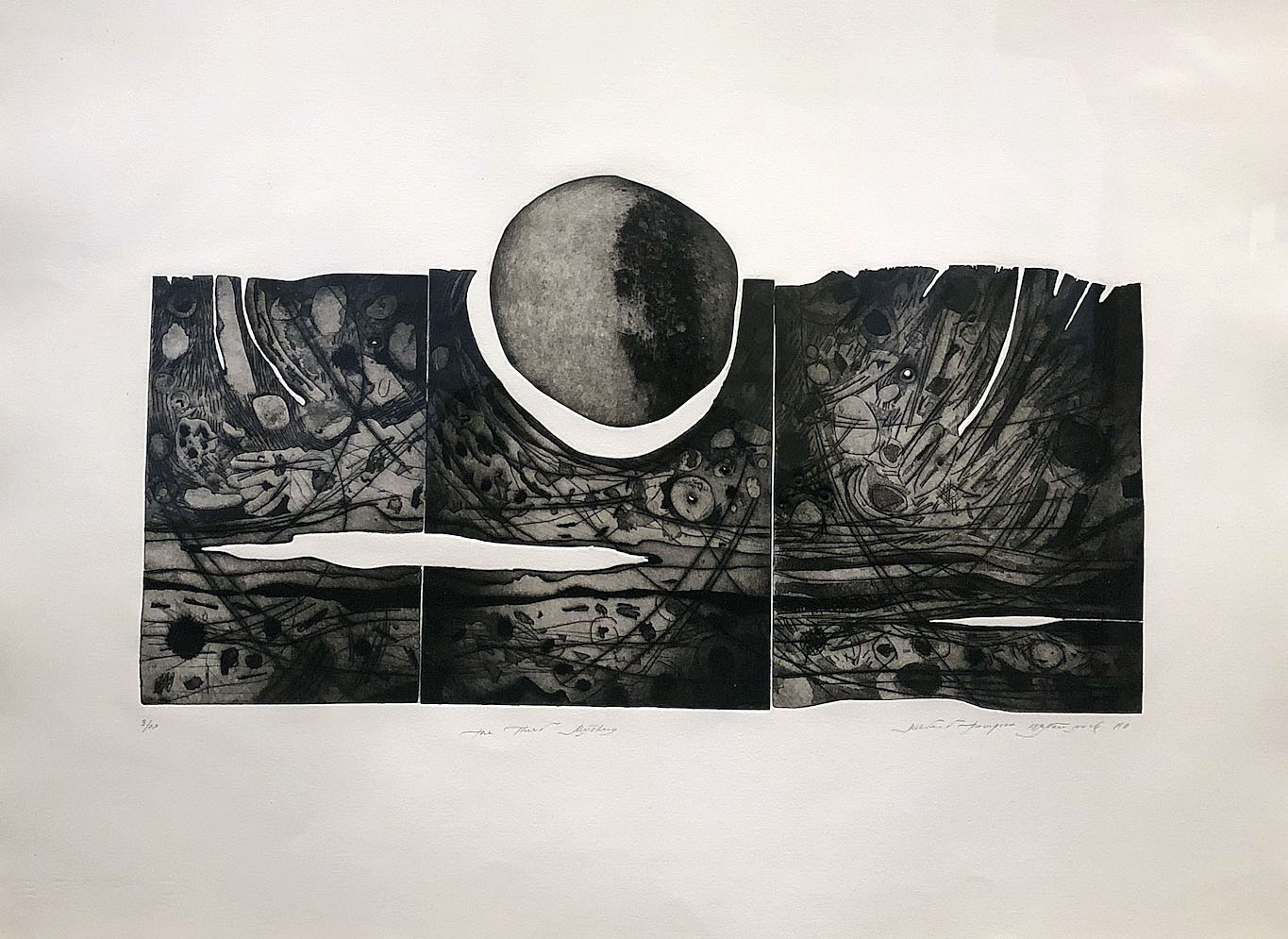

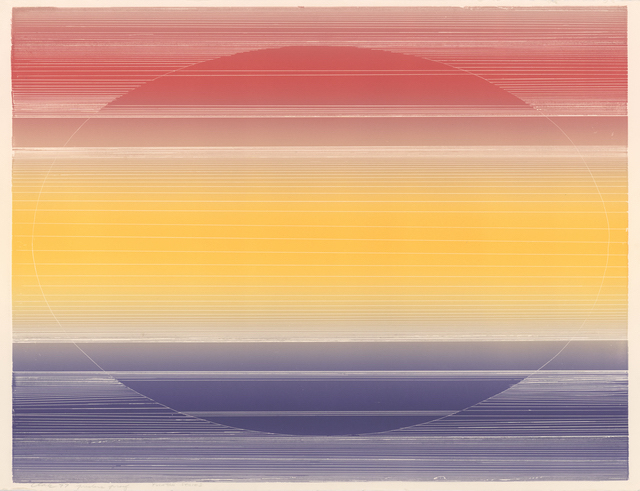

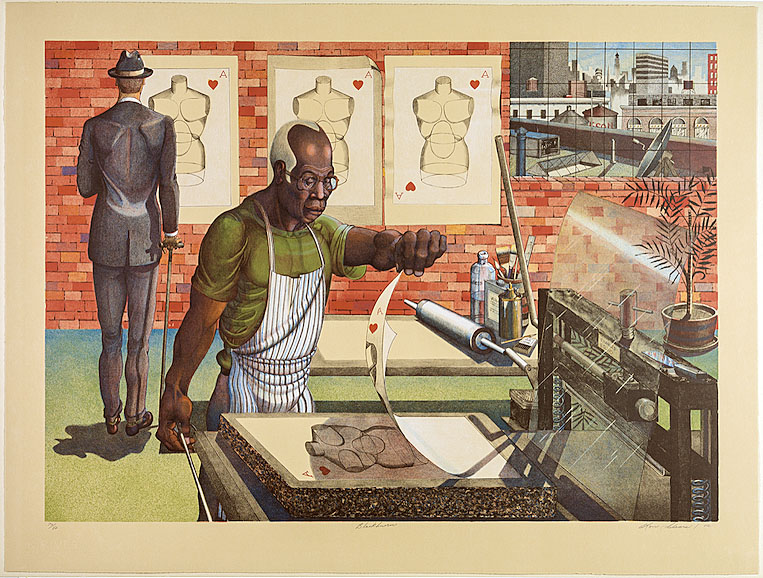

In the adjacent hall gallery, prints and posters highlight Cranbrook’s influential graphic design program. Installed next to printed media that feature collage, photomontage and progressive typography, several unique works hint at the endless formal potential of paper as a medium. Elizabeth Youngblood’s elegant, silvery process drawing is tucked into a corner near Laurence Barker’s more exuberant hand-made paper piece. Layers from the Disemboweled Series by Winifred Lutz takes the medium into the realm of expressionism.

Yet Untitled by Elizabeth Youngblood (MFA Design, 1975) 2018, paint, mylar. Photo: Glenn Mannisto

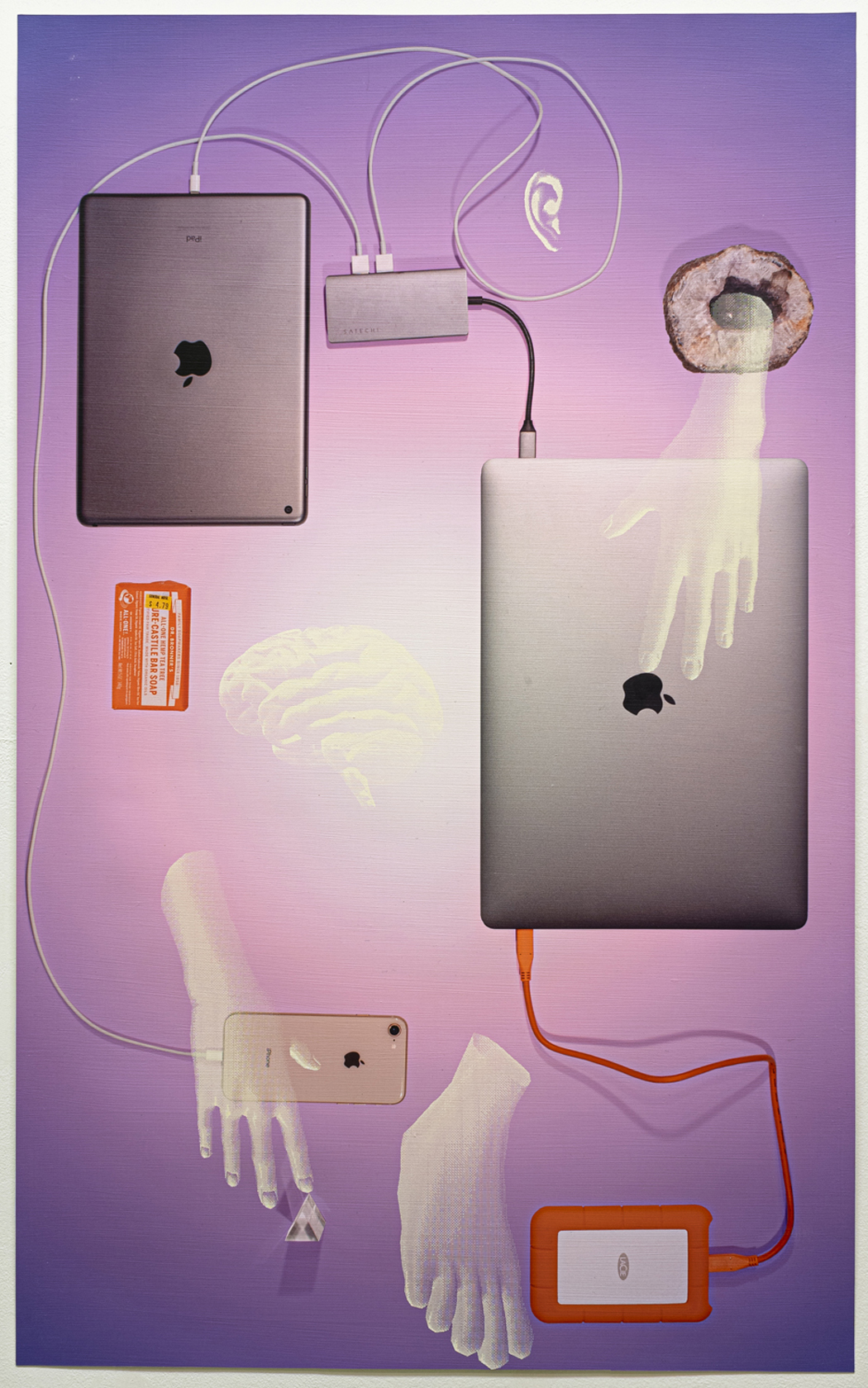

And last–but not least–some of Cranbrook Academy’s most recent graduates inhabit the lower level deSalle Gallery with distinction. Many of these young artists currently live and work in Detroit and continue the Academy’s tradition of excellence in both craft and conception. The growing diversity of the school is on display here, pointing to a more inclusive future, now enabled by the recent $30 million gift from Dan and Jennifer Gilbert to support student diversity. Ricky Weaver’s gray and white photo-apparitions emanate spirituality, across from Ebitenyefa Baralaye’s Portrait II, a comic-sinister stoneware head. Around the corner, Marianna Olague’s painting El Pleno Dia seems to emit its own light. The emerging artists in this gallery demonstrate the continuing influence of the Academy’s alumni on the Detroit art scene and beyond.

With Eyes Opened is multi-faceted, rich and a little chaotic, more of a class reunion than a retrospective. What comes through loud and clear in this exhaustive–and sometimes exhausting–survey, though, is the Academy’s continued vitality and its ongoing relevance to any discussion of the 21st century designed environment. And really, that’s enough.

Cranbrook Museum of Art, With Eyes Opened, deSalle Gallery, installation, Photo: P.D. Rearick.

Eyes Wide Open at Cranbrook Museum of Art through September 19, 2021