The Detroit Institute of Arts presents Van Gogh in America

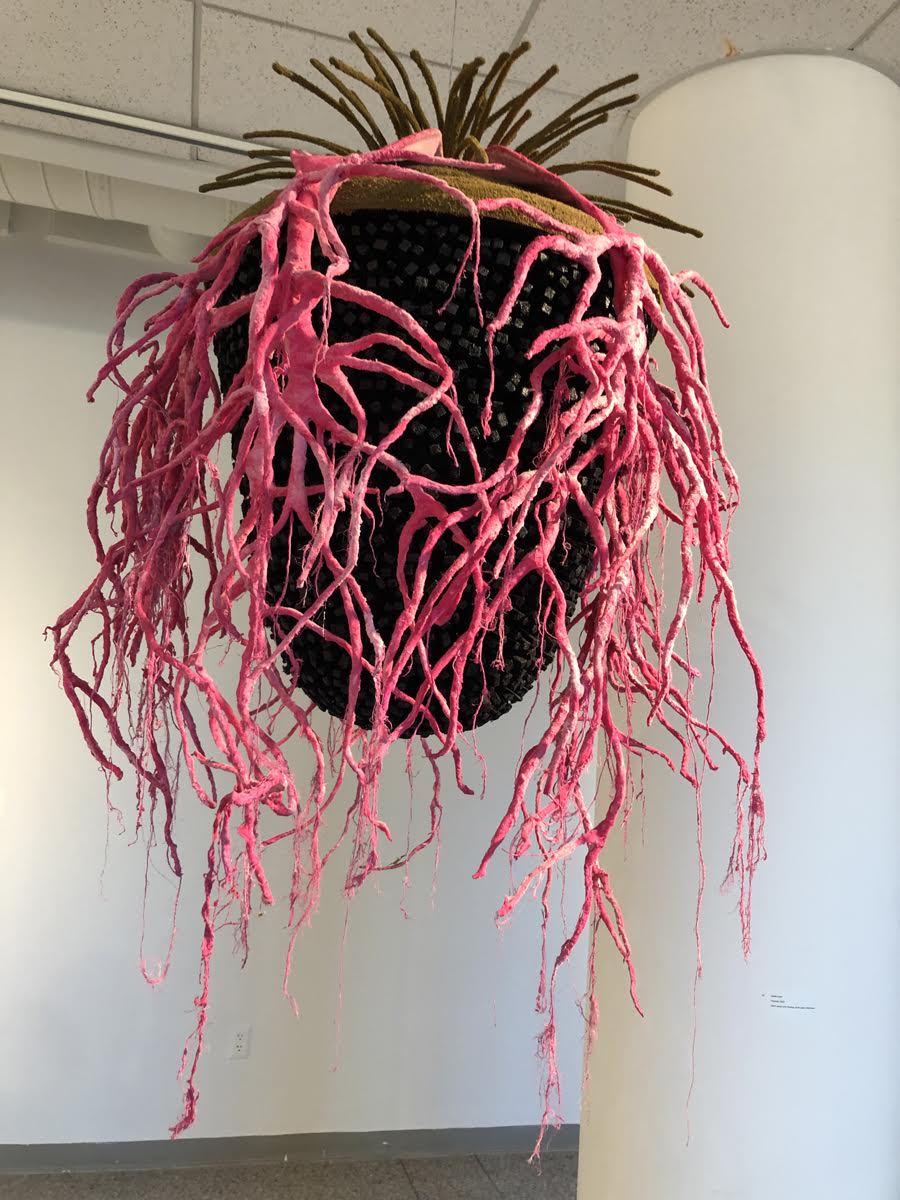

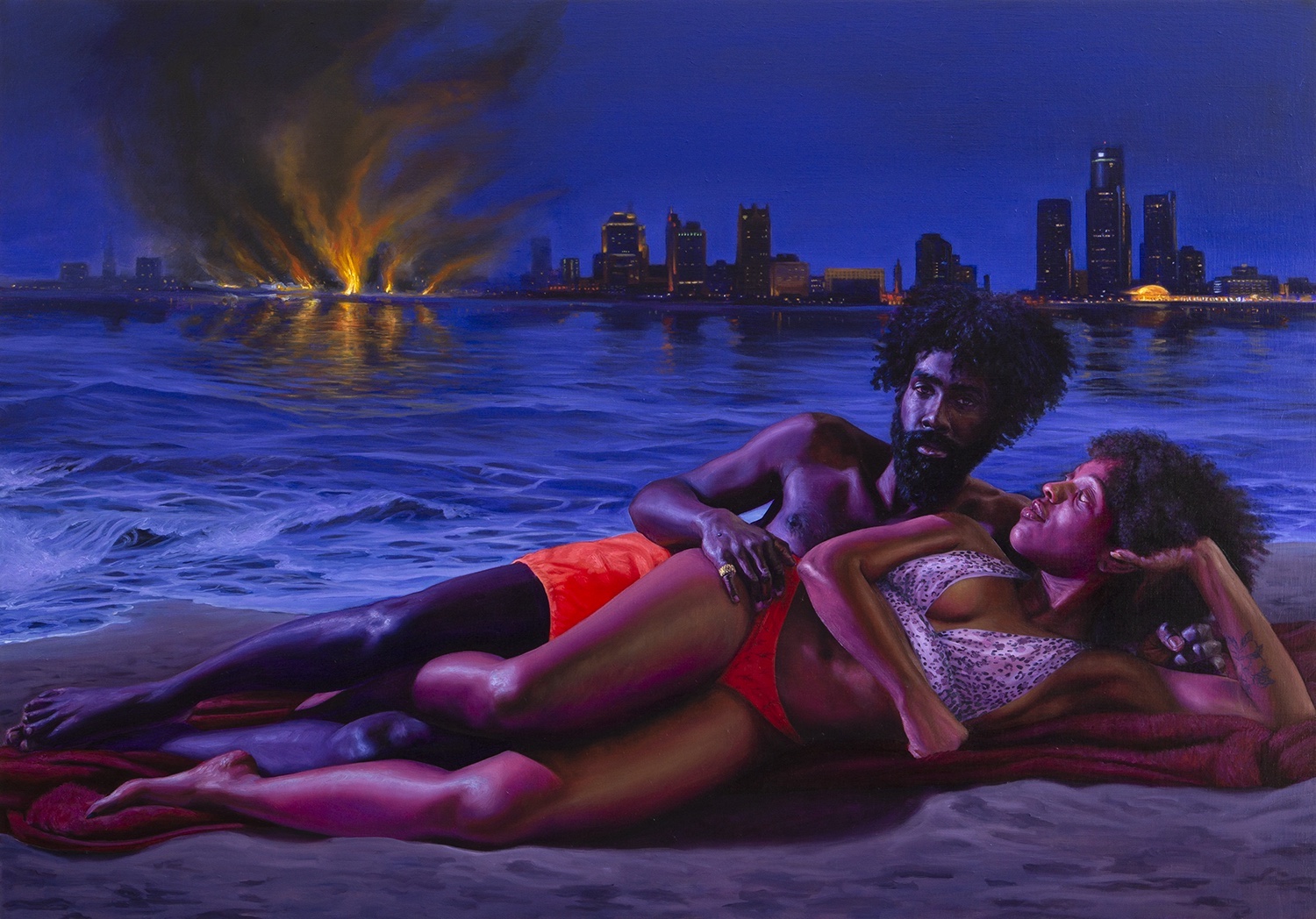

Installation image, Van Gogh in America, Detroit Institute of Arts, 2022

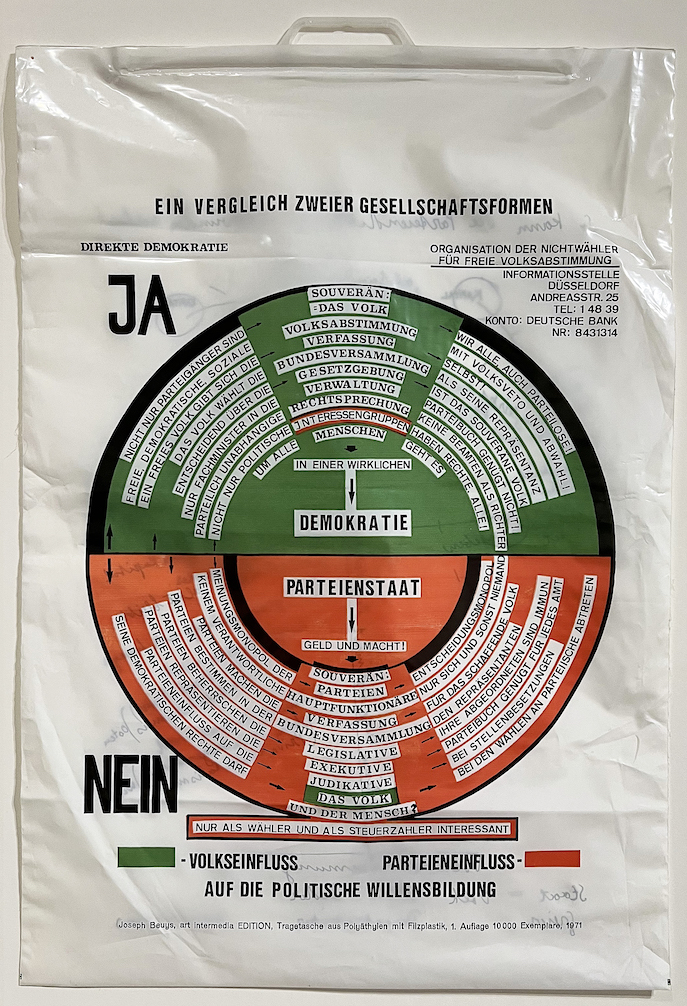

The Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) presents a landmark exhibition, Van Gogh in America, that features 74 works of art that opened on October 2, 2022, and will run through January 22, 2023. The DIA celebrates being the first museum in the country to purchase a painting by Vincent van Gogh in 1921. The work, Self-Portrait (1887), was purchased at a New York auction by Ralph Booth, then the President of the City of Detroit Art Commission. There are nine galleries of artwork, and the exhibition includes a section of Van Gogh’s contemporaries, including Paul Cezanne, Paul Gauguin, Henri Matisse, Raoul Dufy, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, and Joseph Stella.

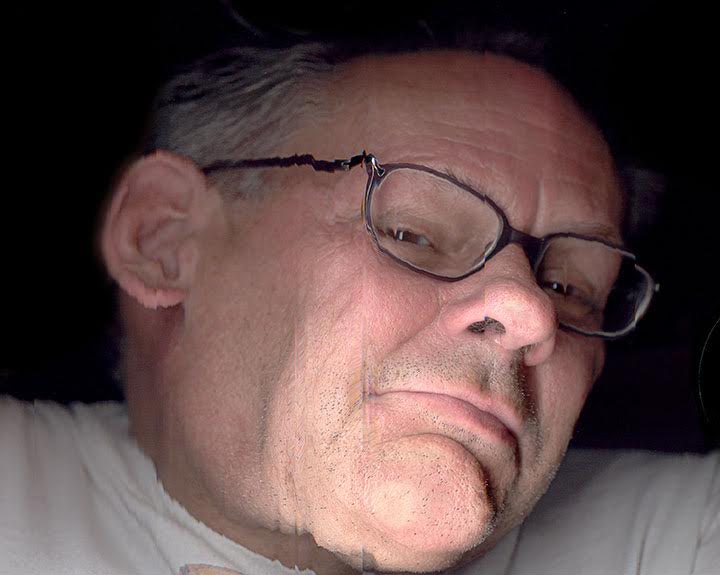

Self-Portrait, Oil on board mounted to wood, 13 x 10″ Detroit Institute of Arts, 1887

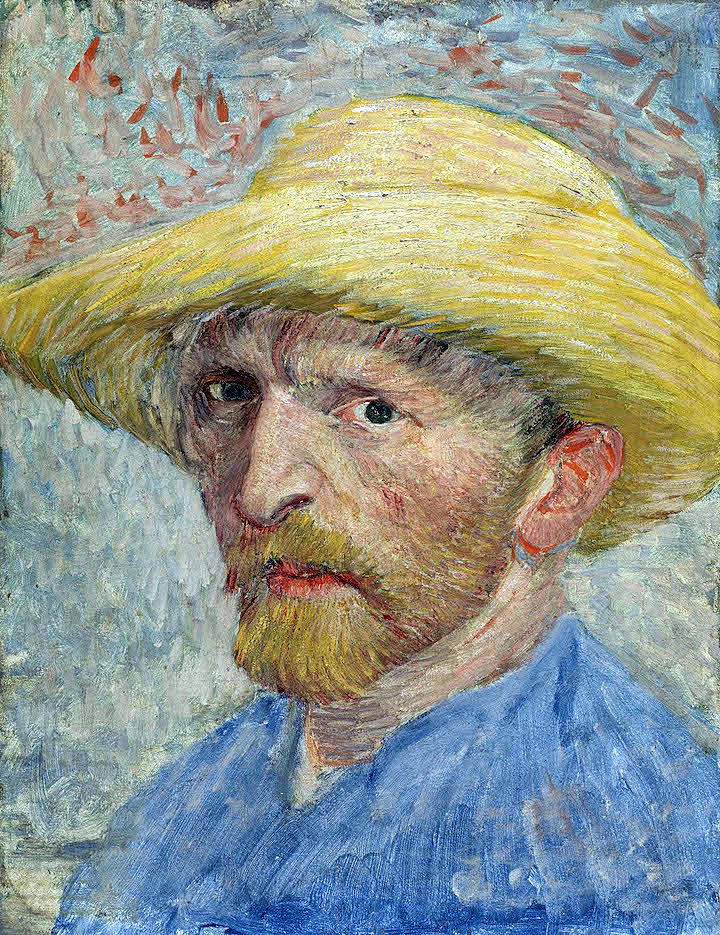

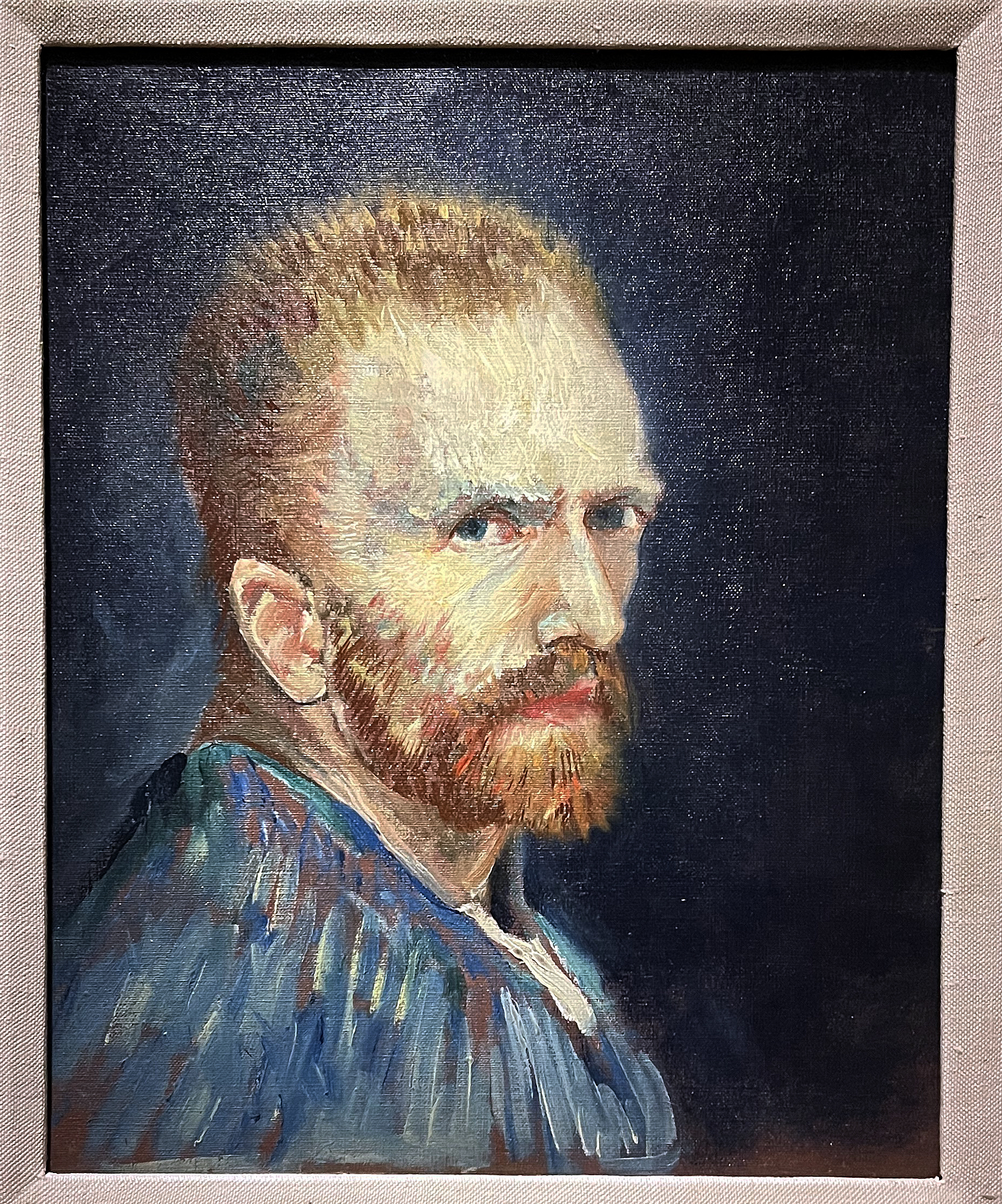

Van Gogh painted more than forty self-portraits and loved to scrutinize his features which, unlike those of the 17th century, might be considered disturbing or unattractive. That, in itself, could not be more introspective. Van Gogh could not find or pay for models, so he used his image reflected in a mirror to create an extensive collection of variations of himself: An indication of his introverted nature.

Self-Portrait, Oil on Canvas, 16 x 13″, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum, 1887

The director of the DIA, Salvador Salort-Pons, says, “One hundred years after the DIA made the bold decision to purchase a van Gogh painting, we are honored to present Van Gogh in America. This unique exhibition includes numerous works that are rarely on public view in the United States and tells the story – for the first time – of how Van Gogh took shape in the hearts and minds of Americans during the last century.”

The works of Van Gogh and his images are ubiquitous in the United States, the Western world, and beyond. There was the novel by Irving Stone, Lust for Life (1934), followed by Vincente Minnelli’s film adaptation, starring Kirk Douglas, which shaped the artist’s popularity. In the mid-1970s, Leonard Nimoy starred in a one-person play called Vincent that he’d adapted from the play Van Gogh by Phillip Stephens. That set the stage for the songs by Don McClean’s Vincent and Starry, Starry Night, and numerous films and theater presentations like Loving Vincent, the world’s first hand-painted, animated feature film, in 2017. Recently there has been the Immersive Van Gogh, a light show based on his imagery, and I would be remiss if I did not mention the book cover of Gardner’s Art Through the Ages was printed from the image of the painting Starry, Starry Night. And these mentions are only a few of the different ways Van Gogh’s work has been used artistically in our culture.

For readers of this review, an easy way to explore the life of Vincent van Gogh is this video produced by the Van Gogh Museum. It may set the stage.

Courtesy of the Van Gogh Museum – 4:50 Minutes

When Van Gogh lived and worked in Paris for two years, he made friends with many artists who were part of the new impressionism that differed from the highly respected artists of the Hague School, sometimes known as the Barbizon School, working exclusively in the tradition of realism.

One of his favorite painters was the French artist Jean-Francois Millet (1814-1875), who featured peasants and rural settings in the countryside. The common themes were waterways, seascapes with boats, windmills, and canals. Millet’s work may have lingered in his mind, but along came this small stroke of paint with variations of color that would come to dominate many of the spaces in his compositions. Clearly, Van Gogh wanted to use color for its expressive value rather than make faithful replicas of the images received by the eye in realism.

It took six years and a team of professionals to create this exhibition. Scheduled to open earlier in 2020, that opening was delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic. This exhibition is part of the Bonnie Ann Larson Modern European Artist Series. The curatorial effort was led by Dr. Jill Shaw, Head of the James Duffy Department of Modern and Contemporary Art, and Rebecca A. Boylan and Thomas W. Sidlik of European Art, 1850–1970 at the DIA. In her statement, Dr. Shaw says, “Van Gogh in America examines the landmark moments and trajectory of the artist becoming fully integrated within the American collective imagination, even though he never set foot in the United States.”

Van Gogh’s Chair, Oil on Canvas, 36 x 28″, The National Gallery London, 1888.

The DIA exhibition of these 74 works of art opens with The Chair as a welcoming image to the show’s first gallery. Painted in December of 1888, when the relationship between Gauguin and Van Gogh had become strained, Van Gogh paints two chairs, the second being Gauguin’s, as his dream of sharing a studio with his close friend was rapidly disintegrating. Van Gogh’s simple chair sits empty, absent of its owner, and is an infinitely lonely image. It is an extraordinary instance of propelling a most familiar object beyond the realm of still life so that it comes to represent the artist himself.

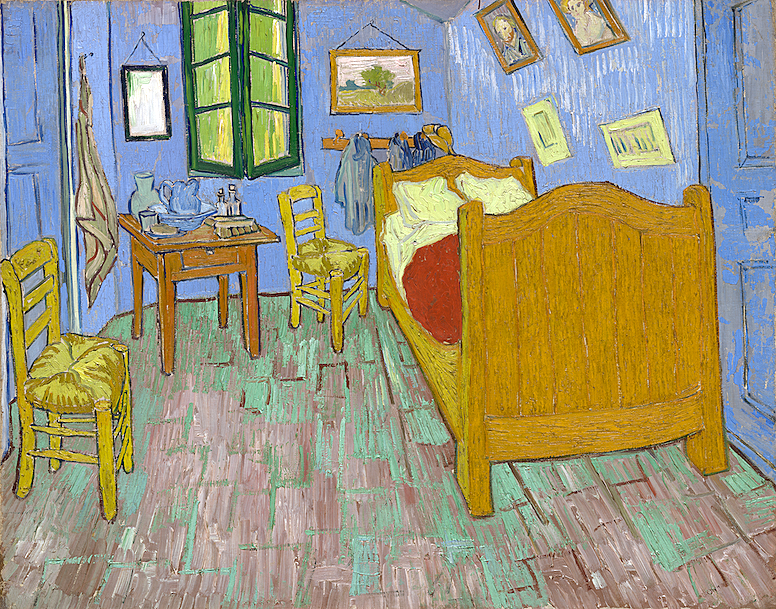

The Bedroom, Oil on Canvas, 29 x 36″, Art Institute of Chicago, 1889.

Van Gogh painted this interior three times while he stayed in the Yellow House in Arles, France, as he was particularly pleased with the bedroom where he had a bed, a small table, and two chairs. This moment marked the first time the artist had a home of his own.

He wrote to his brother, Theo, “It amused me enormously doing this bare interior. With a simplicity à la Seurat. In flat tints, but coarsely brushed in full impasto, the walls pale lilac, the floor in a broken and faded red, the chairs and the bed chrome yellow, the pillows and the sheet very pale lemon green, the bedspread blood-red, the dressing-table orange, the washbasin blue, the window green. I had wished to express utter repose with all these very different tones.”

Portrait of Postman Roulin, 32 x 25”, Oil on Canvas, Detroit Institute of Arts, 1888.

Van Gogh painted Joseph Roulin and his family several times each, and the painting here is the second version painted in early August 1888. There were at least seven portraits of Roulin, as he befriended not only the man but his entire family. He found affordability in the work of the Roulin family, for which he made several images of each person. In exchange, Van Gogh gave the Roulins one painting for each family member. One cannot imagine how the strokes of color in his beard appealed to van Gogh and this relatively new application of oil paint. The painting was acquired in 1935 by Edsel and Eleanor Ford as a gift to the DIA.

Fishing Boats on the Beach at les Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, Oil on Canvas, 25 x 32, Van Gogh Museum.

It was in February of 1888 that Van Gogh was living in Arles and would take excursions to Provence and the village of Les Saintes-Marie-de-la-Mer. Van Gogh would have liked to have made this painting on the beach, but the fishermen would put out to sea every morning, so he would make his drawings early and finish the painting in his apartment studio. In doing so, he could control his choice of color to his liking, using primary color juxtaposed with secondary color in the boat composition.

Starry Night (Starry Night Over the Rhone), Oil on Canvas, 28 x 36″, Musee d’ Orsay, 1888.

The DIA takes the visitor out of the exhibition with Starry Night Over the Rhone, which is just what this review will do. Just a two-minute walk from the Yellow House, painted in 1988, the subject is the night light and its effects on the river Rhone. The view from the east turn in the river towards the western shore of rocks is where Arles was built. After spending his days in the sunny fields of flowers and crops, the idea of painting at night must have intrigued Van Gogh. Here the gas lights from the town are complemented by the formation of the stars. Van Gogh writes to his brother Theo, “This morning I saw the countryside from my window a long time before sunrise with nothing but the morning star, which looked very big.” As it turns out, The Starry Night is one of the most recognizable paintings in western art.

On March 17, 1901, 71 of Van Gogh’s paintings were displayed at a show in Paris, and his fame grew enormously. Van Gogh’s sister-in-law, Johanna, had collected as many of Van Gogh’s paintings as she could but discovered that many had been destroyed or lost as Van Gogh’s mother had thrown away crates full of his art. His mother lived long enough to see her son hailed as an artistic genius.

Today, Vincent van Gogh is considered one of the greatest artists in human history.

I would like to distinguish between experiencing all the places one sees the remnants of Van Gogh’s artwork versus observing the original artwork up close in the DIA. That is one of the purposes of the museum. Educators and researchers refer to this experience as being in the presence of a “primary source.” Primary sources are what remains from the past. Aside from human memory and the unrecorded passing down of information from generation to generation, experiencing original paintings are the only way current generations can hope to understand what an authentic Van Gogh painting looks and, more importantly, feels like. In my later years, and over time, I have seen Vincent van Gogh paintings in various museums, but I never saw 74 artworks in one place. From so much that was written about him, Vincent van Gogh was a fragile and sensitive man burdened with poor health. As an artist, he became an instant soul mate to many. He was dependent and vulnerable but always willing to make himself available to his audience.

Take advantage of this opportunity to spend quality time at the Detroit Institute of Arts and join family and friends to view this extraordinary exhibition Van Gogh in America.

Installation image Van Gogh in America, Detroit Institute of Arts

Van Gogh in America celebrates the DIA’s status as the first public museum in the United States to purchase a painting by Vincent van Gogh, his Self-Portrait (1887). On the 100th anniversary of its acquisition, experience 74 authentic Van Gogh works from around the world and discover the fascinating story of America’s introduction to this iconic artist in an exhibition only at the DIA.

A full-length, illustrated catalog with essays by the exhibition curator and Van Gogh scholars will accompany the exhibition. The Detroit Institute of Arts is the exclusive venue for this exhibition.

Tickets are $7-$29 for adults; discounted prices are for residents in Wayne, Oakland, and Macomb counties. The DIA exhibition Van Gogh in America will run through January 22, 2022