Parish, Parish, Parish – An exhibition of painting by Tom, Shirley, and Erin Parish

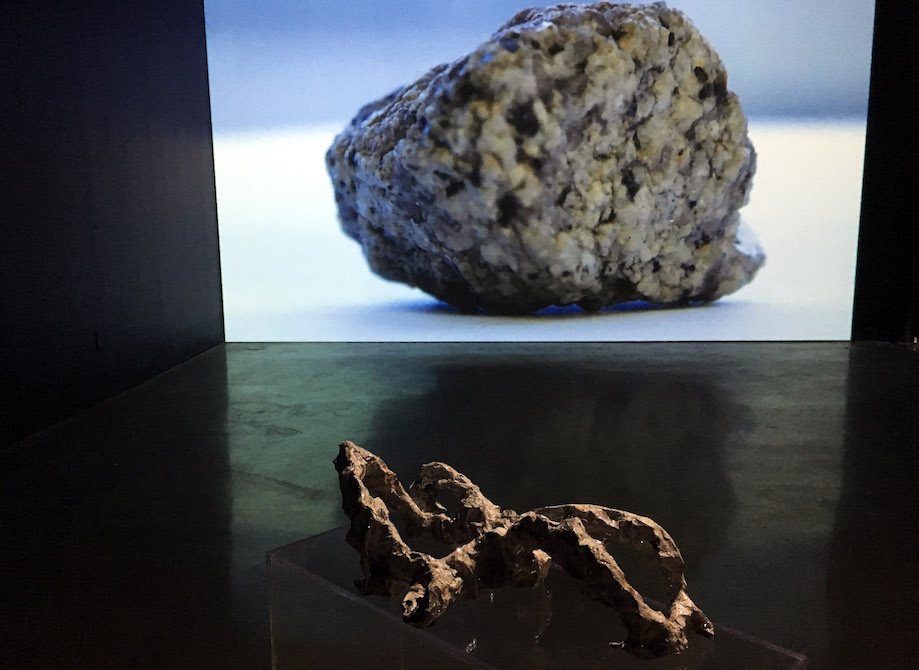

Installation image, Courtesy of Shelia Kniffin, 2017

In downtown Detroit, where Grand River Ave. meets and Griswold St. in the Zemco Textile building, circa 1977, Tom & Shirley Parish lived and painted in a loft on the 6th floor. They each had a studio, as did the young daughter, Erin who has just turned 12 years old. At the time, Detroit was going through some of its hardest times, making this kind of space affordable for artists but back then, the family had some concerns about safety. Fast forward thirty years, Tom Parish, Emeriti’s Professor of painting from Wayne State University now works in his studio in Southfield, as does retired art teacher Shirley Parish, and Erin Parish has just opened a one-person exhibition Meet Me Halfway at Art & Art Gallery, in Miami Florida. This will be her 32nd solo exhibition. These three artists from one family are presented together in the current Ellen Kayrod exhibition, Parish, Parish, Parish, in mid-town Detroit, connected by oil paint and an incredible sensibility of purpose to their paintings.

Erin Parish, Shirley Parish, Tom Parish, (left to right) Image Courtesy of Lucille Nawara

Erin Parish, after her undergraduate work at Bennington College and an MFA at Queens College, NY established herself as a Miami-based artist who paints fields of colorful abstract forms. Most recently these circular forms are activated through a vivid palette of repetition that evokes a sense of space, depth, and volume. The work is a combination of canvas, mixed media and, polyester resins that communicates contemplation as it draws the viewer into this new abstract experience.

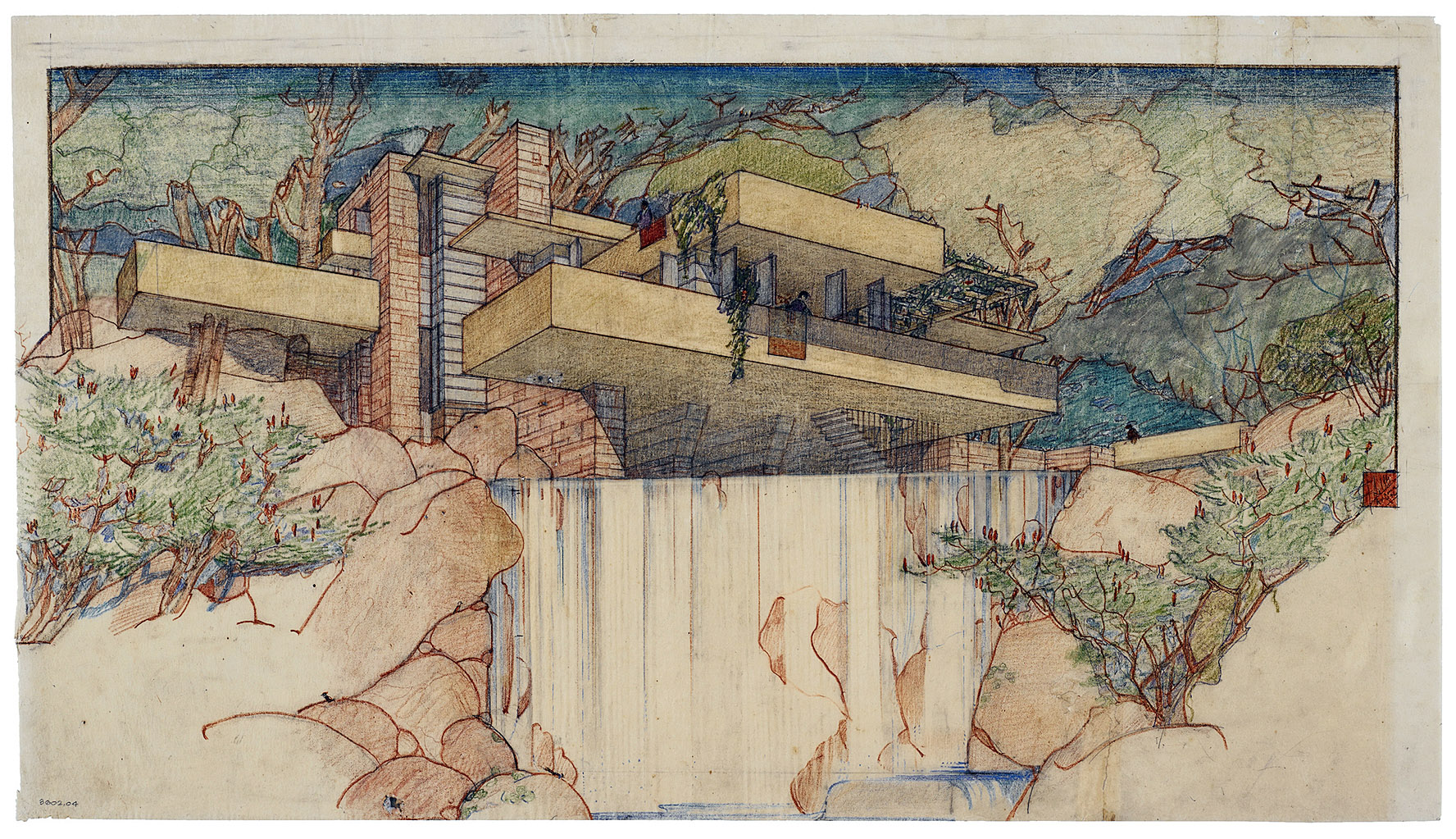

Erin Parish, Auspicious Flying Dream, Oil on Canvas, 2008

She says in her statement, “Things, in my paintings as in life, are always in the process of becoming: the edge of things about to be, flux, impermanence, thawing, growth, and the change of the seasons. Spring was a most joyous time of year after a long white winter with low gray clouds and a little sun in my hometown of Detroit. This touches on the Buddhist insistence on impermanence and how this resonates with me.”

And in a recent book by Deepak Chopra, The Spontaneous Fulfillment of Desire, he captures an idea that resonates with her paintings, “At a deeper level, there is really no boundary between ourselves and everything else in the world… we are all constantly sharing portions of our energy fields, so all of us, at the quantum level, at the level of our minds and our “selves”, we are all connected.

Shirley Parish, Red Bird, Oil on Canvas, 2017

Shirley Parish, Egret, Oil on Canvas, 2017

Shirley Dombrowski Parish has been working with oil paint imagery for forty years and has exhibited extensively through out the Detroit Metro Area since the late 1970’s. This new work based on bird symbolism comes after a period that focused on cloud creations where she described that work for the Detroit Art Review, “The painting of the sky began after many years of studying landscape. I try to capture light and breeze. I am aware of the constant shifting of light reflection of the sky, the sunset, water. The light is forever changing. These paintings are perceptions of experience, a visual poetry.”

But in recent years these elongated bird creatures have provided the subject matter that brings representational ideas out of abstraction. The painterly surface, rich and controlled, provides a bookmark for her recent work. She describes her several summers of vacationing on Beaver Island as an influence on her interest in the bird motif. She says in her statement, “After studying birds for two years, I decided to give a new twist to the sky. Creating the paintings has been a great adventure. These works of large birds capture feeling that can only arise through the painting of birds. The consciousness of the bird has empowered my creativity, gathering information through the inner-self, manifested through conscious and subconscious intelligence.”

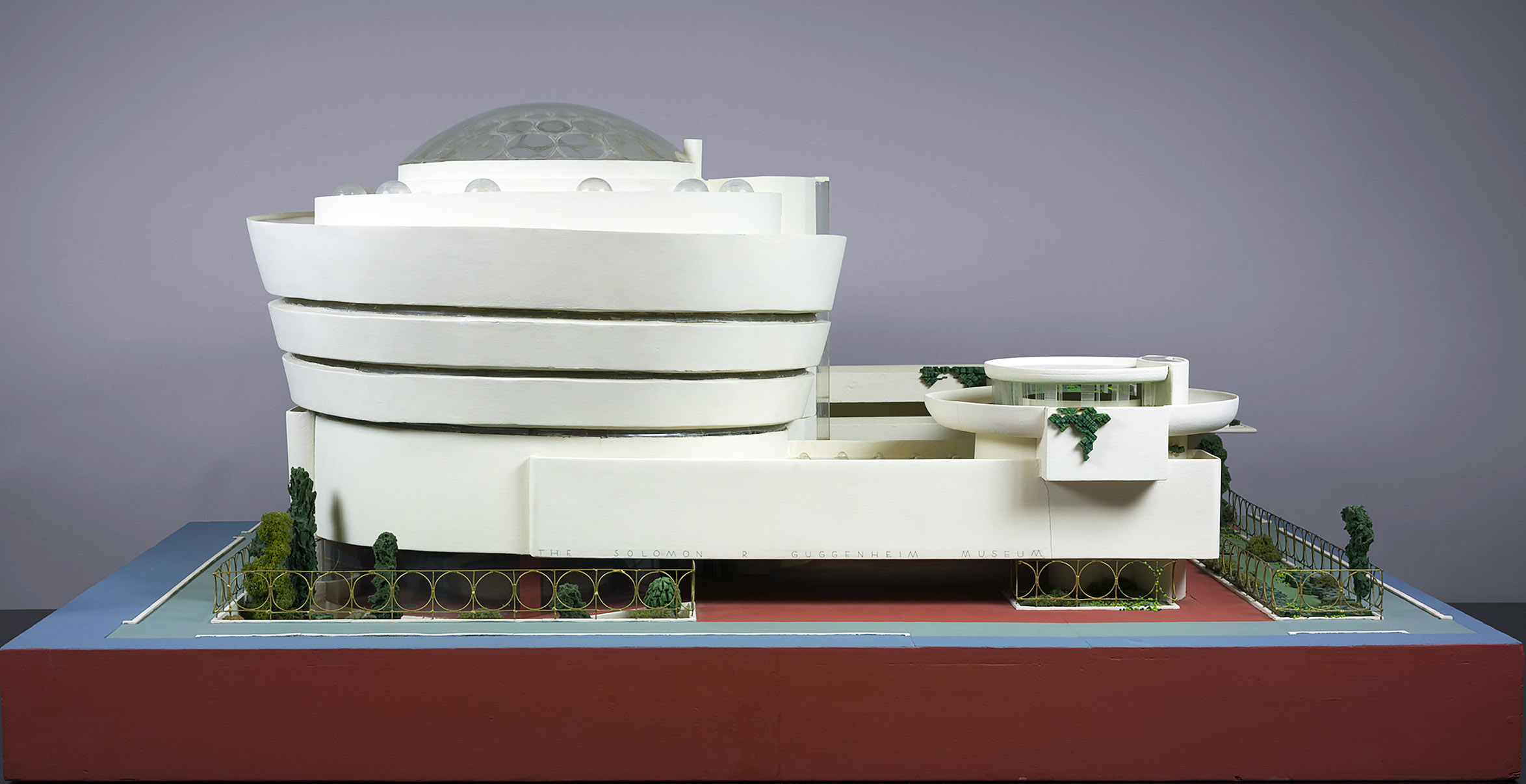

Tom Parish, Sogna, Oil on Canvas, 2017

In Detroit, the Ellen Kayrod Gallery has become a familiar space for artist Tom Parish to reveal new work. For nearly thirty years he as made a sojourn to Venice, Italy to capture the architectural compositions of water and light. His time in Venice is always spent on observation and capturing images photographically during a two-, sometimes three-week stay. The images are both inspiration and part informational in creating what I have called a magical realism.

In the work Sogna, the image is a salty worn section of architecture and swirling reflections of light on water combined with reflection-struck water in the turbulent canal. The underlying strength in Parish’s work is always compositional. Here we get a slice of sky and a corner of open sea with a building facade having exterior and interior space to ponder. Parish reaches back to everything he had experienced in his reading to his observations of Cezanne, combined with a lucid imagination, to form special longitudes of form and gentle reflections of light.

It took an American painter, Thomas Parish, from Hibbing, Minnesota, home to the musician Bob Dylan, to find the landscape in Venice, part of the shallow Venetian lagoon and an enclosed bay that lies between the mouths of the Po and the Piave Rivers. His Venetian landscapes expose the beauty of both, the architectural setting and swirls of reflective water that transcends a soft blend of magnitude and mystery.

Ellen Kayrod Gallery Parish, Parish, Parish – on view until December 8, 2017