Charles White: A Retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, New York City, NY

Charles White (American, 1918–1979). General Moses (Harriet Tubman). 1965. Ink on paper, 47 × 68″ (119.4 × 172.7 cm). Private collection. © The Charles White Archives. Photo courtesy of Swann Auction Galleries

If there’s a fearsome female gaze that can make Manet’s icy Olympia seem coy and puerile by comparison, it’s that of the determined Harriet Tubman, rendered in ink by Charles White during the height of the Civil Rights movement. Famous for liberating hundreds of slaves during the Civil War, here she becomes a contemporary symbol for racial equality, and could, with little imagination, plausibly be seen among those marching on the front lines across Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. She’s emblematic of White’s work, which unfailingly depicted black America with strength, regality, and dignity.

Born in 1918 on Chicago’s South Side, African-American artist Charles White began his career inauspiciously as a sign painter; he would later become one of the most accomplished draftsmen of his generation. His style had extraordinary reach, ranging from the gently abstracted figures that peopled his WPA mural paintings of the late 1930s to his tight and refined graphite and ink drawings of the 1960s. Charles White: A Retrospectiveis a muscular show that snugly fills half of the MoMA’s third floor with over 100 drawings, paintings, and other ephemera. White’s first major show in 30 years, this traveling exhibition champions the enduring appeal of figurative drawing, and his socially-conscious subject matter keeps his work uncannily relevant.

Arranged chronologically, the retrospective begins with his early paintings, produced when White was a freshly minted graduate from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1938. His early mural Five Great American Negros is an early tour de forcethat established several of the tropes that defined much of White’s subsequent career. Painted when he was just 21 for a fundraiser for Chicago’s South Side Community Art Center, the painting celebrates Booker T. Washington, Frederick Douglass, George Washington Carver, Marian Anderson, and Sojourner Truth. The mural’s heaving landscape and figural distortions rhyme with the regionalist paintings of Thomas Hart Benton, but, as ever, White’s work also spoke to contemporary social injustices. He painted the mural in 1939, the same year that gospel singer Marian Anderson was refused permission by the Daughters of the American Revolution to perform at Constitution Hall because of her race, and her inclusion in the work freights the painting with timely relevance and political weight.

Charles White (American, 1918-1979). Five Great American Negroes. 1939. Oil on canvas, 60 x 155″ (152.4 x 393.7 cm). From the Collection of the Howard University Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.© The Charles White Archives/ Photo: Gregory R. Staley

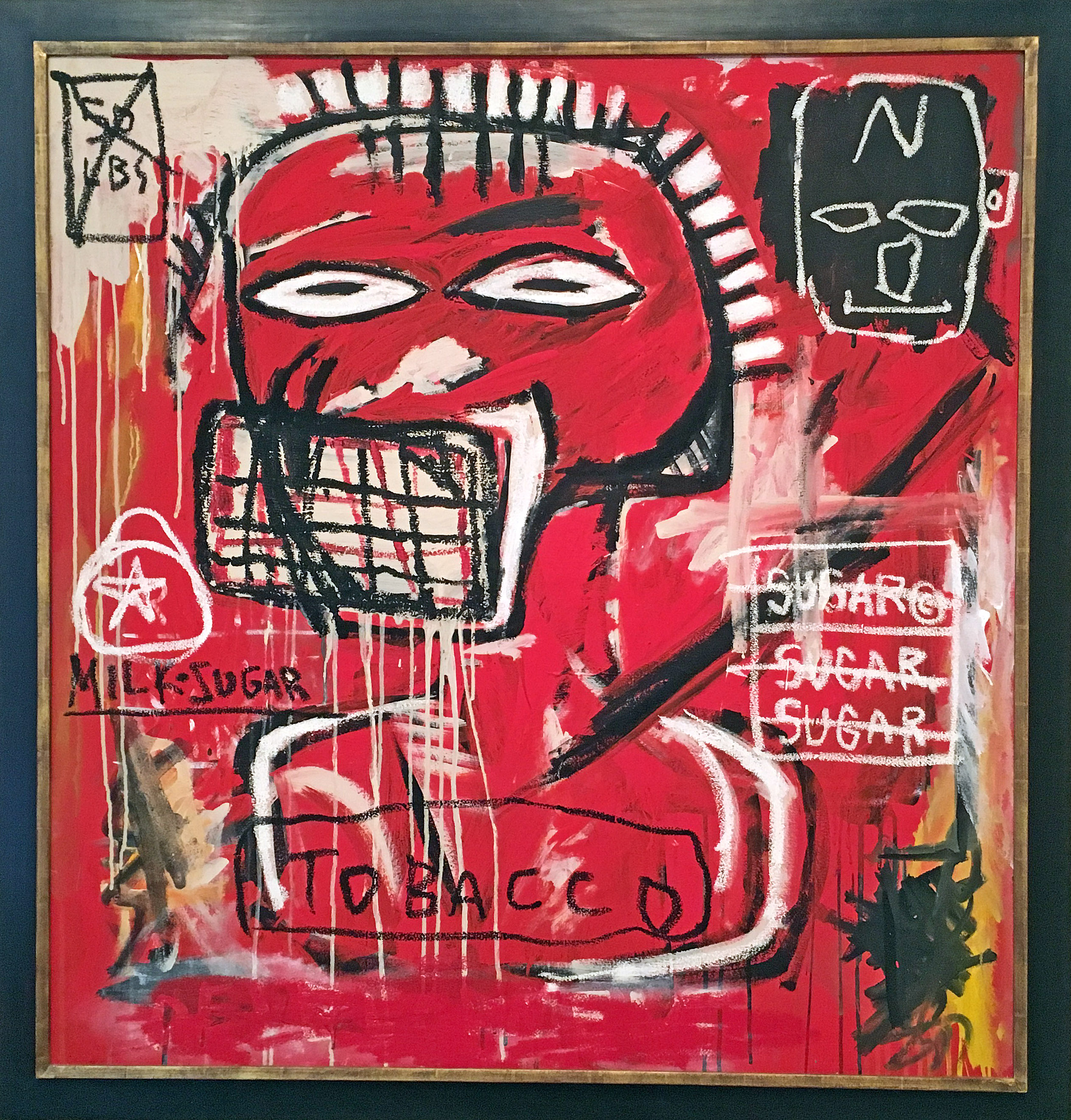

Charles White believed that artists had a moral obligation to contribute to social discourse, and to this end his work aggressively addressed racial injustice and economic disparity in America. In the 1940s and 50s White produced soulful and moving works like There were no Crops This Year, a Steinbeckian depiction of a visibly distraught husband and wife; an empty sack which the woman holds is the only prop in the drawing, but it’s enough to tell their story. And his poignant and incriminating proto-cubist Headlinesdepicts a visibly distraught woman flanked by a veritable blizzard of news headlines that reveal instances of racial inequality in America. His use of collage and text mirrors the synthetic cubist experiments of Picasso and Braque, but here White masterfully harnesses the vocabulary of cubism and channels it toward social protest.

Charles White (American, 1918-1979). Headlines. 1944. Ink, gouache, and newspaper on board, 20 x 16″ (50.8 x 40.6 cm). Collection of William M. and Elisabeth M. Landes. © The Charles White Archives/ Photo: Gregory R. Staley

But while his works frequently addressed racial and economic inequality, White managed to avoid producing an oeuvre drearily burdened by politics. His brightly painted Gospel Singers radiates joy, and the strong, pitchfork-wielding woman in Our Land (White’s witty response to Grant Wood’s American Gothic) radiates confidence, determination, and, above all, dignity.

Music also played a significant role in his output, and he produced affectionate drawings of gospel singers Mahalia Jackson, Paul Robertson, and Bessie Smith. White created cover designs for a series of jazz albums by Vanguard Records, and in 1965 his illustration for Gould: Spirituals for Orchestra received a Grammy nomination for best album cover. But the musical collaboration this show especially highlights is that of Charles White and Harry Bellefonte, whose recorded voice croons uninterruptedly throughout the exhibition space. Bellefonte commissioned works by White, often including them on his television show, and White responded with several portraits of the singer, head thrown back, utterly abandoned in music. Fittingly, because of the close relationship White had with so many musicians, the MoMA has thoughtfully assembled a Spotify playlist of music inspired by the show—there’s everything from old spirituals to gospel music and James Brown.

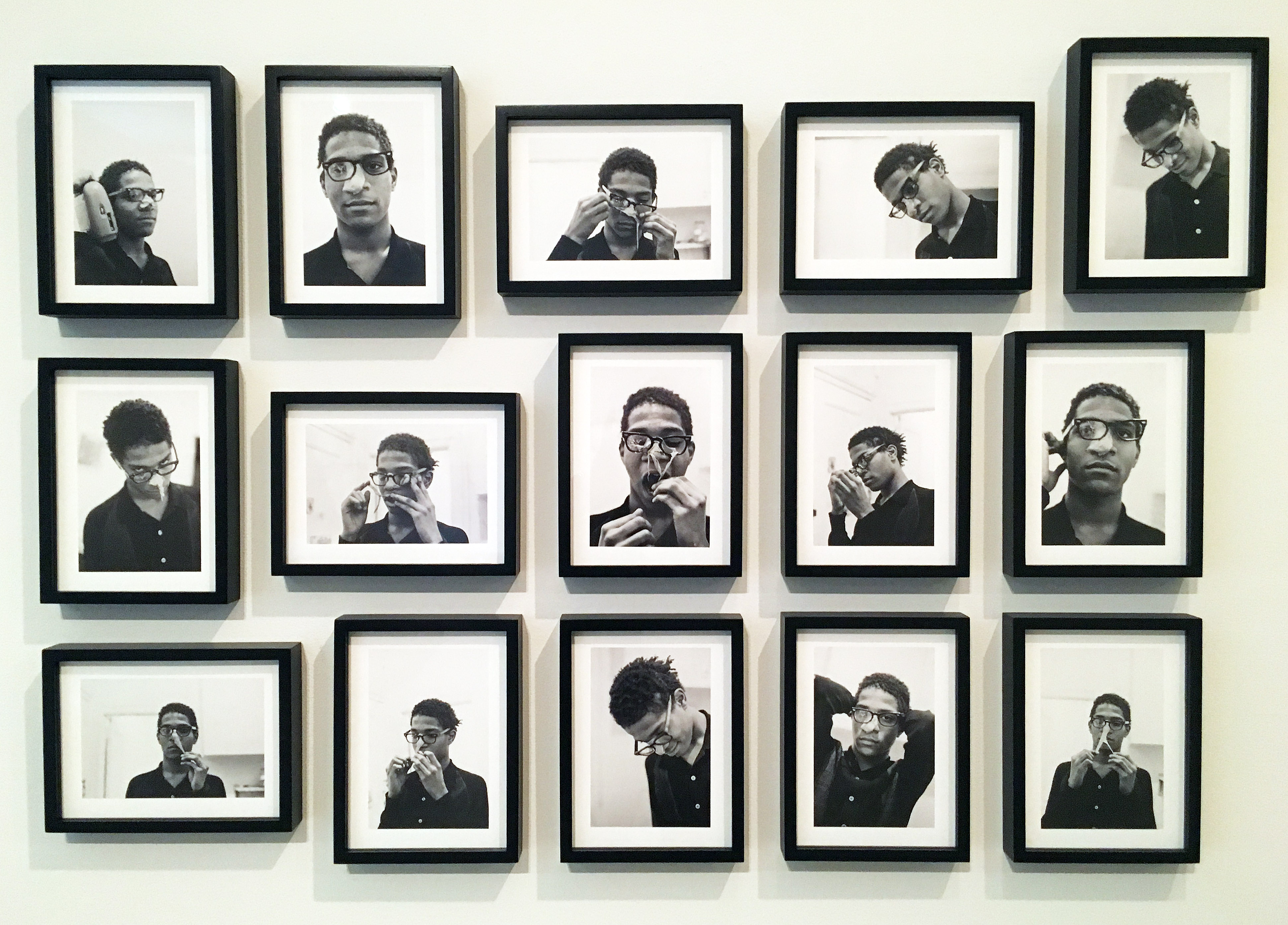

In the 60s and 70s, White’s work continued to address social justice and civil rights, but his style became increasingly crisp, a marked departure from his previous abstracted depictions of the figure. It’s a stylistic shift made apparent in his 12-part series J’Accuse (“I accuse”), a series of confrontationally large ink drawings collectively named after Emile Zola’s open letter to the French government in which Zola famously defended Richard Dreyfus, a Jew wrongfully convicted of murder. The series’ title equated American racial inequality with European Antisemitism, but the drawings themselves refrain from directly referencing any instances of injustice. Rather, White gives viewers affectionate and sensitively rendered portraits of black Americans, often set against a stark white background, and allows for their innate dignity to speak for itself.

Charles White (American, 1918-1979). J’Accuse #7. 1966. Charcoal on paper, 39 1/4 × 51 1/2″ (99.7 × 130.8 cm). Private collection. © The Charles White Archives/ Photo courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

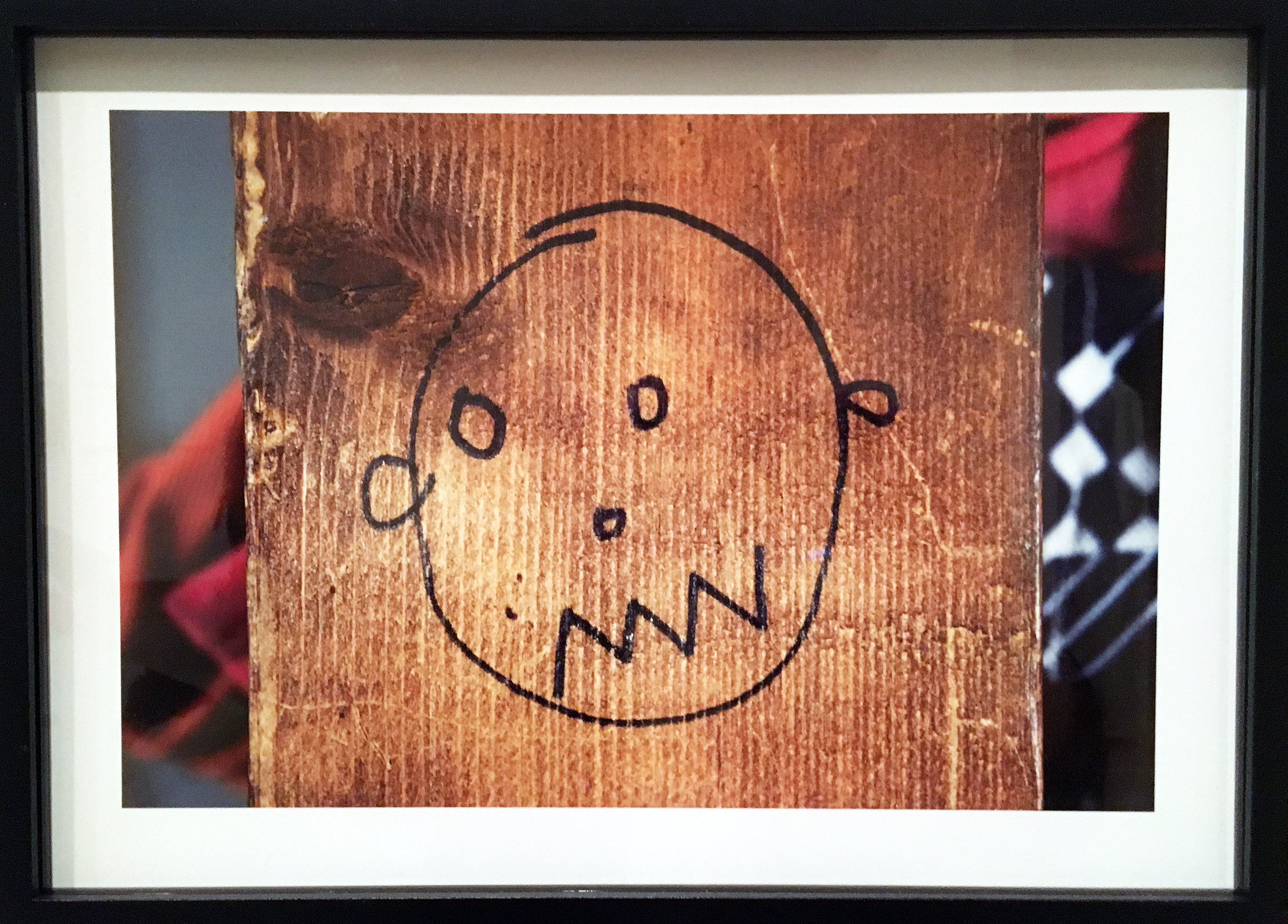

The final room in the retrospective includes several works from his acclaimed Wanted Posterseries, a cycle of 21 monochromatic oil-wash and lithograph works which emerged from White’s frustration at the slow pace of the implementation of civil rights in America. Appropriating the imagery of old wanted posters for runaway slaves, all the works in this series mimic the texture of crumpled newsprint in arresting tompe l’oeil. Barely-discernable stenciled-in words help the viewer navigate the meaning behind these ambiguous works; in one especially poignant image, a mother stands behind her son, both their faces registering utter sorrow; above her head hovers the form of an eagle and the word “sold.”

One of the final images viewers encounter is White’s iconic Black Pope. Closely resembling the Wanted Posterseries in its color and texture, the painting depicts a man wearing clothing reminiscent of priestly vestments, flashing what could be interpreted both as the peace symbol, or the sign Christ makes in icons while bestowing a blessing. Barely discernable, “Chicago” is stenciled atop the image, and the figure wears a sandwich board which proclaims with calculated ambiguity: “NOW”– an all-encompassing call to action.

Installation view of the exhibition Charles White: A Retrospective.October 7, 2018–January 13, 2019. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Digital Image © 2018 The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo by Robert Gerhardt.

Charles White: A Retrospective is a massive show made even more impressive when we consider that the overwhelming majority of these works are fastidiously rendered figurative drawings—there are no easy shortcuts to quickly fill wall space. Furthermore, while his drawings are impressively large, they always reward close inspection with their varied stippled and hatched-in textures. Today, his work hangs in many of America’s great museums—the Metropolitan, the Chicago Art Institute, and the Smithsonian, to name a few. But his legacy isn’t just the art he created, but the many students who emerged under his shadow, such as Kerry James Martial, who stated that Charles White believed that one’s work “should be in the service of helping dignify people.” His work did exactly that, and this retrospective triumphantly speaks to White’s unflagging and determined mission to portray black America with the dignity it deserved.

Charles White: A Retrospective, through January 13, 2019 at the Museum of Modern Art, NYC, NY.