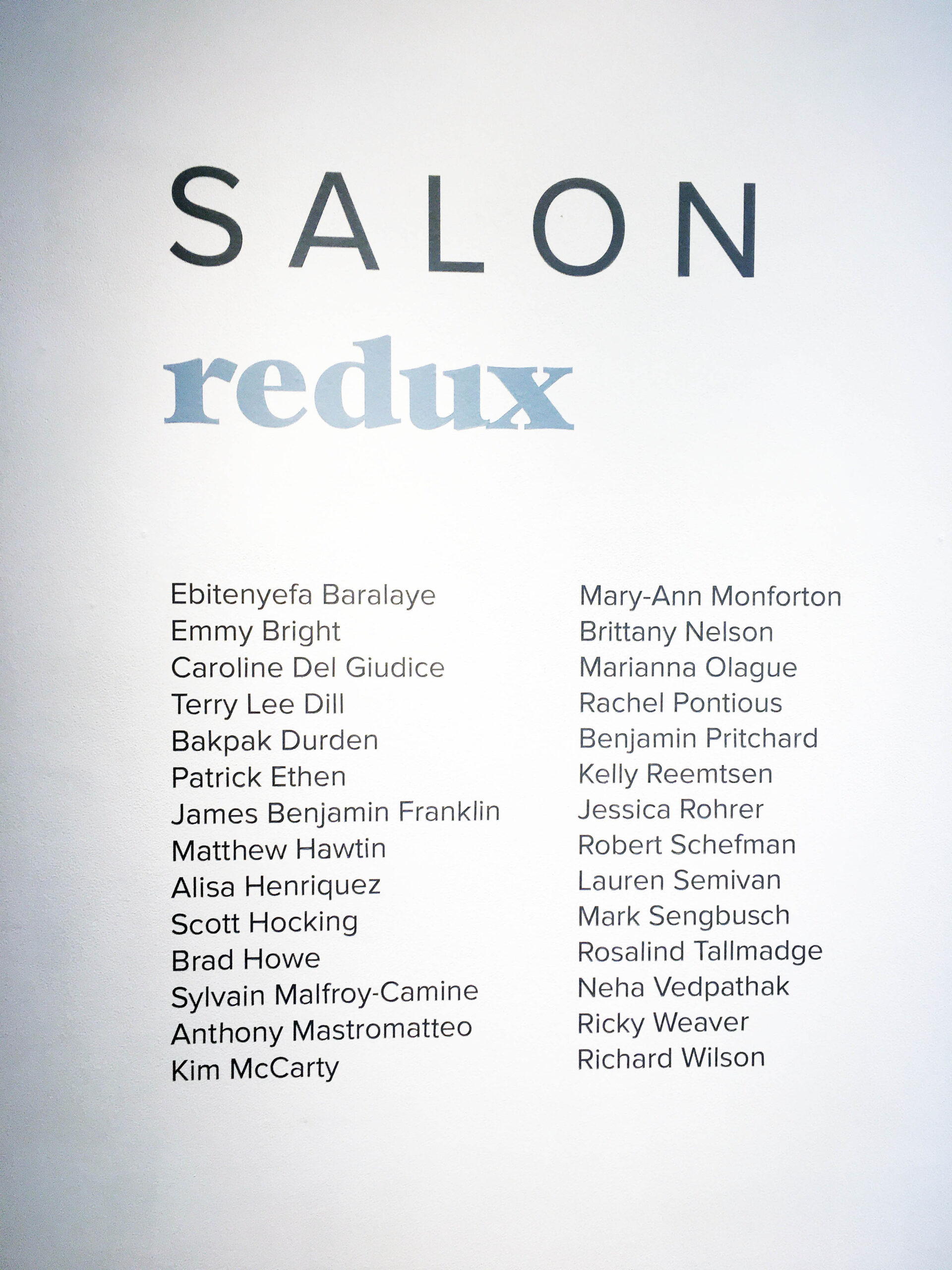

An installation view of “Salon Redux” at Detroit’s David Klein Gallery.

“Salon Redux” at Detroit’s David Klein Gallery is a handsomely staged 28-person group show that includes almost any medium you can hang on a wall (and a couple that sit on the floor), and manages to be a refreshing antidote to lousy weather and other contemporary ills. But you’ll have to move quickly; “Salon Redux” is up only till Feb. 26.

The exhibition was inspired in part, says Christine Schefman, Klein director of contemporary art, by the strong positive reaction to an earlier “Salon” in 2019. “That show had such great energy,” Schefman said, “so we decided to do it again — or ‘redux.’” She adds that it’s a spirited way to kick off the new year, and there’s no denying that.

Twenty-eight artists are represented in the salon-style group show.

Hanging works salon-style, of course, means creating a sort of wall collage, with pieces hung above and below one another in large groupings, rather than the standard approach with everything at eye level and in a single row. (The excellent wall arrangements in “Redux,” by the way, were done by preparator Craig Hejka.)

Three walls are taken up with these narrative groupings, and while they feature very different smallish works, there are a few commonalities linking them. In particular, each wall includes an irregularly-shaped color collage by Cranbrook grad Sylvain Malfroy-Camine, which in a couple cases almost resemble an artist’s old-fashioned wooden paint palette, with irregular splotches of color on a roughly circular background.

The most interesting of the three is “Diving Bell.” With its background of deep-sea blue, the work immediately calls up notions of water, while the spray of dark-blue, green, and yellow ovals covering it – all vertical — resemble nothing so much as bubbles rising to the surface. If you need a tranquil spot to rest your eyes for a minute, this would be a good choice.

Sylvain Malfroy-Camine, Diving Bell – 2021, Oil and acrylic on canvas, 23 1/2 x 26 1/2 inches.

Similarly balming in its way is Detroiter James Benjamin Franklin’s “Roam,” a gorgeous geometric color study of various shapes, with one large, off-balance dot – painted cerulean blue — that looks like it’s tiptoeing across the canvas toward escape. It’s a delightfully unstable element that defines the entire painting. Franklin’s use of colors is instructive as well. The tans, greens, and darker blues absorb light, while a silver streak and a semi-circle of lustrous black pop it right back at the viewer, compounding the visual texture.

Franklin, another Cranbrook MFA, is having a moment – in addition to “Salon Redux,” he’s got a solo show at Reyes Finn in Detroit with nine of his large-scale, abstract works, also up through Feb. 26, 2022.

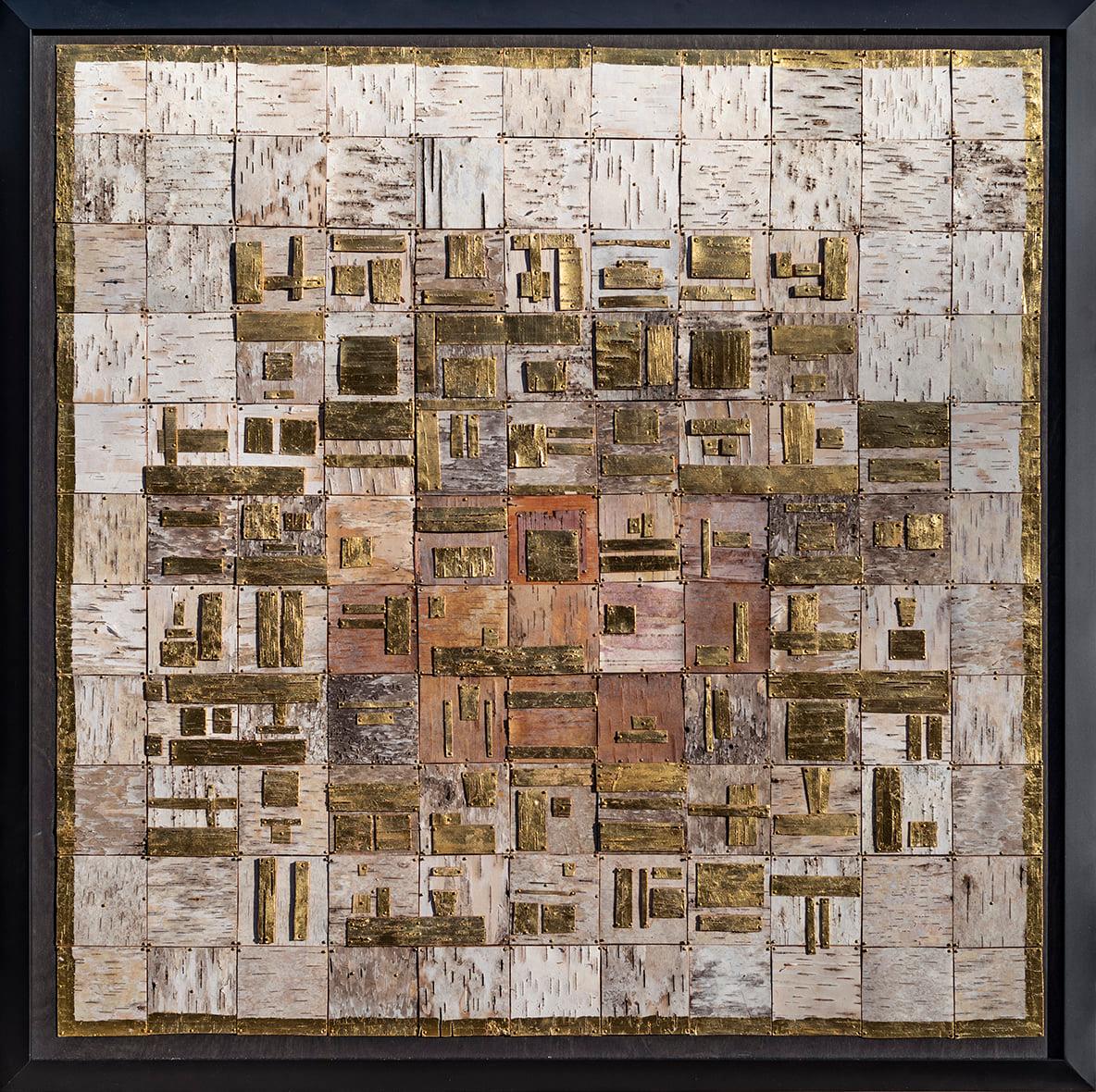

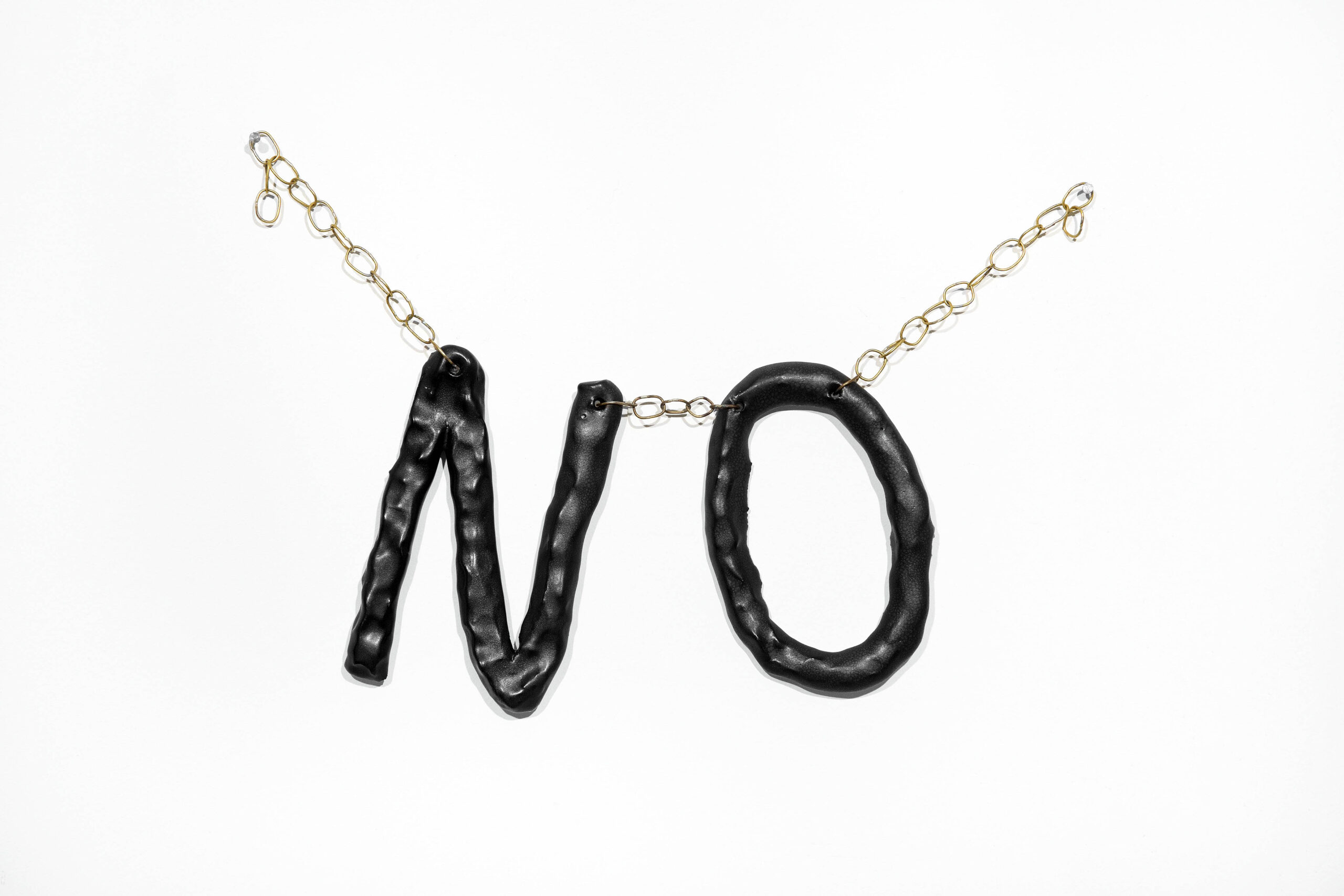

As it happens, Cranbrook enjoys pride of place in this exhibition, claiming 11 of the 28 artists. In addition to Malfroy-Camine and Franklin, there’s Emmy Bright with her “NO, 4/4” – two black ceramic letters spelling out “NO” that hang from a hand-made brass chain. Bright, who co-heads the graduate school’s print media department, often plays with cryptic messaging that at its best toggles between the puckish and the almost-profound. Also well worth a look is Brooklyn artist Rosalind Tallmadge’s copper-hued “Cross Section X,” one of her remarkable layered constructions made of gold leaf and mica that read a bit like aerial views of scarred, metallic moonscapes.

Emmy Bright, NO, 4/4 – 2017, Ceramic, handmade brass chain, Letters 6 x 4 1/2 inches.

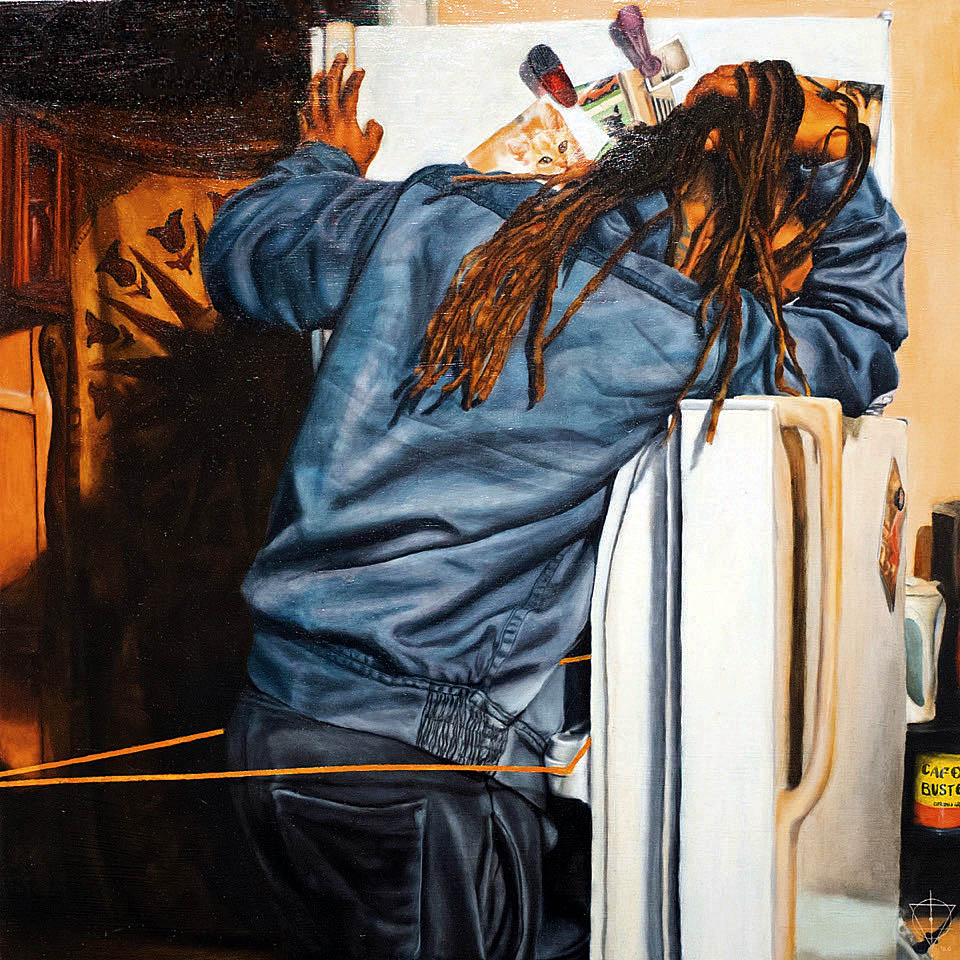

Among figurative paintings on display, Bakpak Durden’s “The Refrigerator” is a bit of an intriguing puzzler. Durden, whose website ID’s him as a “multi-disciplinary, queer, hyperrealistic artist based in Detroit,” has painted a fellow who’s facing away from us. He’s got long dreadlocks and is leaning on a refrigerator’s wide-open door, seemingly looking within for something good to eat. But there are possible clues to a more distressing narrative. Is the subject searching for last night’s leftover steak, or is his face, hidden from us, actually buried in the crook of his elbow that’s propped on the refrigerator door? Is he grabbing his dreads with one hand in an idle gesture, or is it a signal of despair? Adding mystery as well is the outline of a triangle, color orange and completely out of context, albeit fascinating, that’s got the young man within its snare. Meaning — who knows? The can of Café Bustelo coffee on the shelf to the right isn’t saying.

Bakpak Durden, The Refrigerator – 2020, Oil on wood panel, 24 x 24 inches.

On a lighter note, Ohioan Anthony Mastromatteo’s oil-on-gesso-board painting, “My & My & My & My & My & My & My Fight, Too” stars seven identical images of Wonder Woman, a repetition of the exact same cut-out cartoon panel “taped” in each case, one after the other, to a blank blue background. The DC comics super-heroine is sprinting towards us, her thoughts on Artemis, goddess of wild animals and the hunt. Given the me-too moment we’re living in, there seems little doubt some male abuser’s about to get his comeuppance, big-time and bruising. In any case, as a work of art, it’s an oddball, charming concept. (Mastromatteo has a nice touch for unsentimental whimsy. His online resume features a fly at the upper-left corner, casting a little shadow on the CV.)

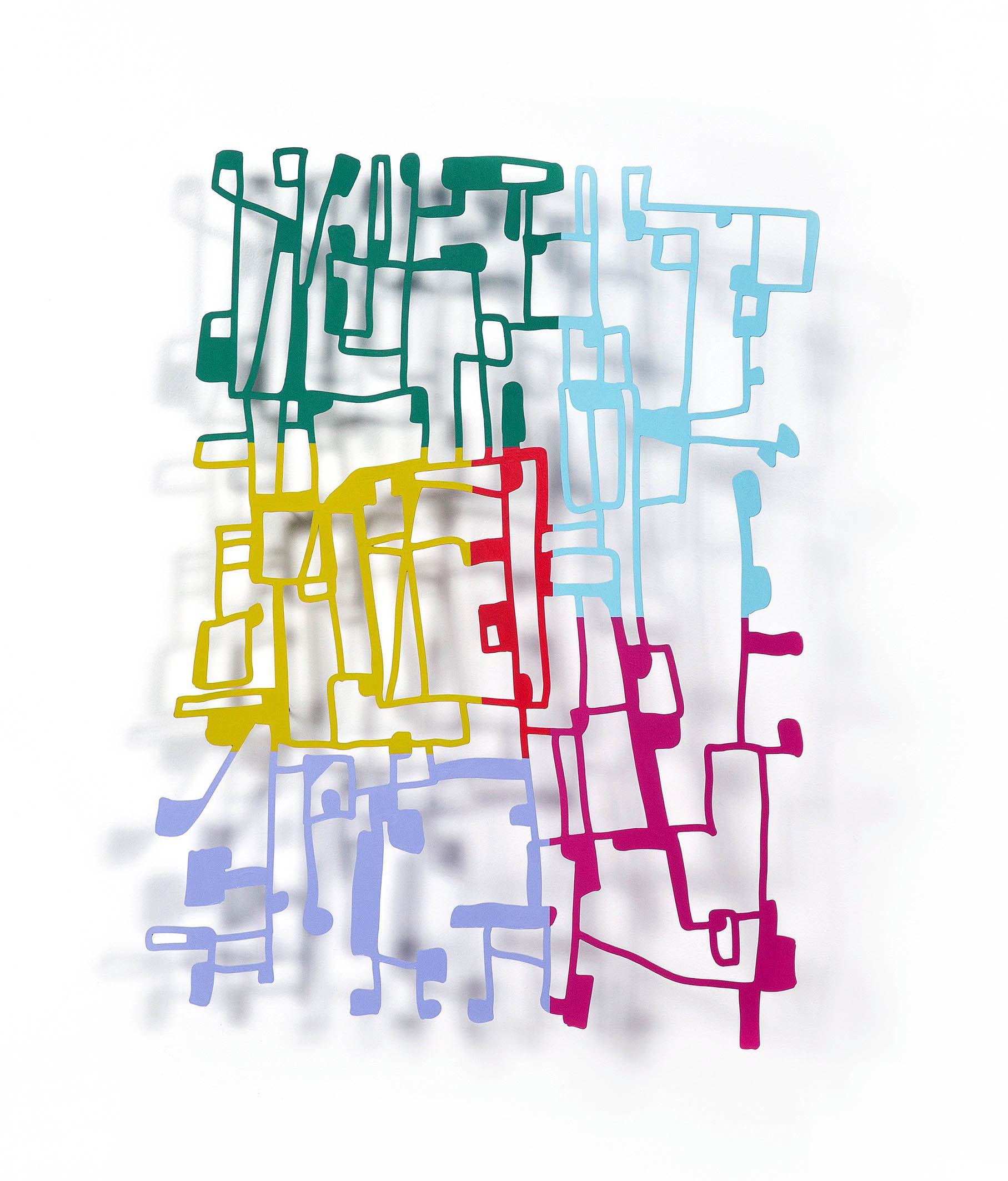

Also lightening the mood are three stainless-steel, fanciful line sculptures by Los Angeles artist Brad Howe, each mounted five inches off the wall. Looking a bit like happy graphics or electronic circuitry, they’re painted in unlikely hues that, magically, all work splendidly together. In particular, “Bingo by the Sea”is a fizzy essay enlivened, like all three compositions in the show, by shadows on the wall beneath that echo the sculpture’s lines.

Brad Howe, Bingo by the Sea – 2021, Stainless steel and acrylic, 24 x 18 x 5 inches.

Worth seeking out as well are New Jersey artist Jessica Rohrer’s two photorealist aerial portraits of tidy, well-kept neighborhoods that look like they could be in Chicago or Detroit – engaging drone’s-eye portrayals of the American Dream that, along with an astringent color palette, feel remarkably fresh. There are also intriguing, minimalist sculptures with light by Detroiter Patrick Ethen and Toronto’s Matthew Hawtin, and in a show that otherwise eschews politics, Brooklynite Mary-Ann Monforton has crafted a sly put-down with “Mar-a-Lago.” It features a clunky dinner place-setting with concrete “silverware,” each piece plastered within an inch of its life in gold leaf — a puckish conceit with bite.

“Salon Redux” will be at the David Klein Gallery in Detroit through Feb. 26.