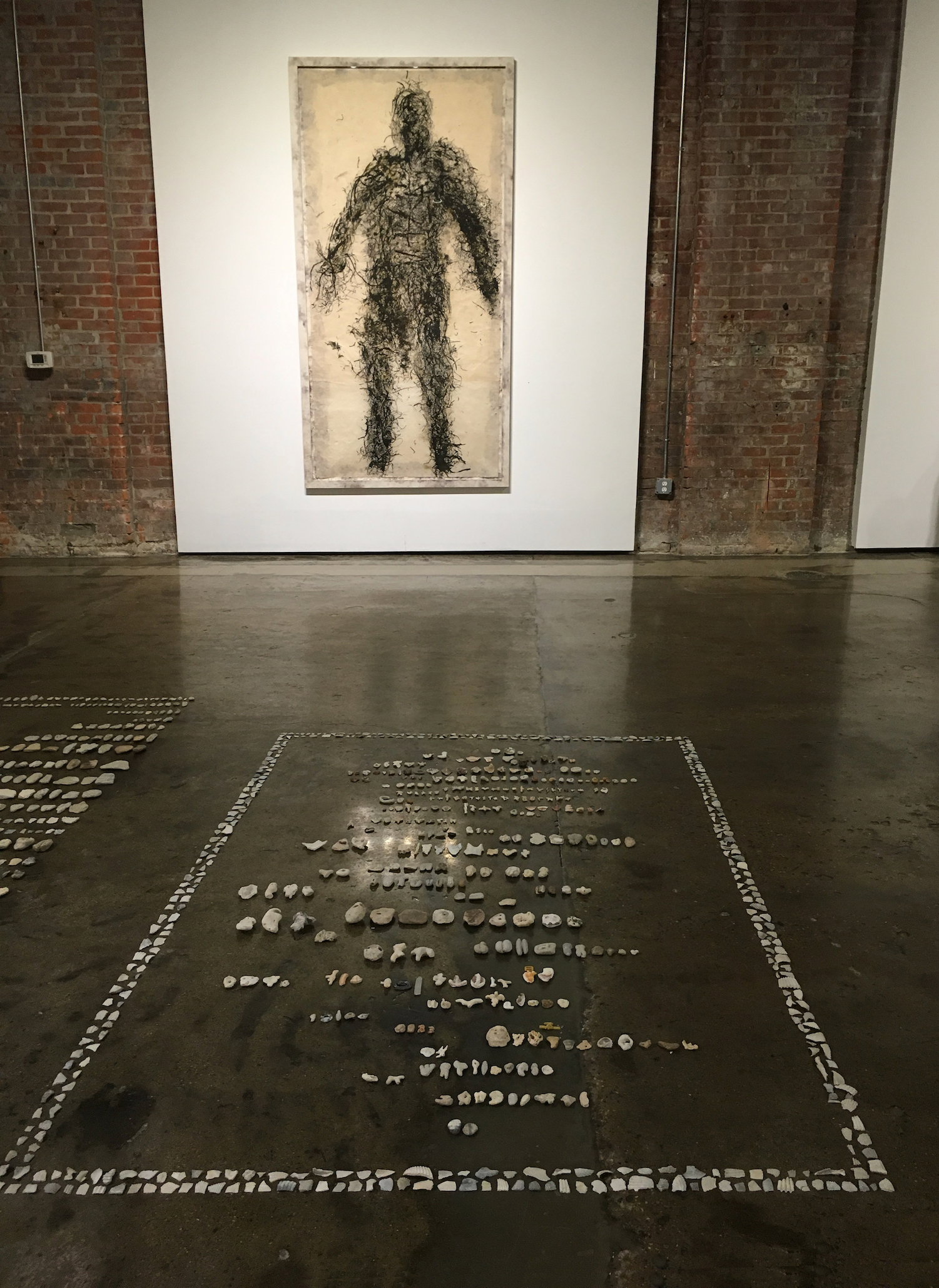

Michele Oka Doner, Hominin Relic, The Release, Fertilized Capsule

Wasserman Projects opened an exhibition February 16, 2018 with the work of Michele Oka Doner, the prolific and inventive maker of sculpture, installations, jewelry, furniture, functional objects and handmade books.

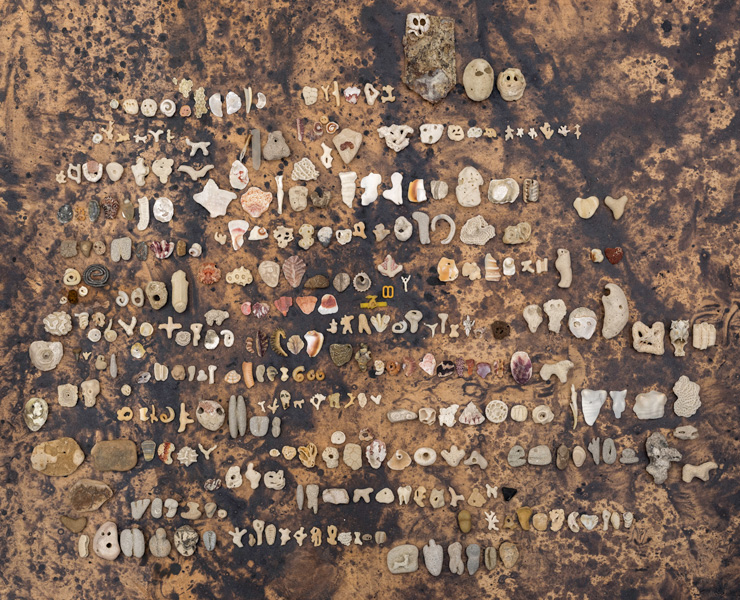

Michele Oka Doner, Life Forms, 2005, Project for the Life Sciences Building at Rutgers University, Piscataway NJ. Wide view of atrium floor. Bronze embedded in terrazzo. Image from The Watch All publication

Her work celebrates organic forms, particularly seashore life, but also seeds, trees, the human body and other forms of natural growth. Michele Oka Doner is probably best known for her creation, A Walk on the Beach, an installation on the floors of Miami International Airport. It is one of the largest public artworks in the world, featuring 9,000 unique bronze sculptures inlaid with mother-of-pearl in over a mile-and-a-quarter long concourse of terrazzo.

I recall meeting her and seeing her work at the Gertrude Kasle Gallery in the early 1970s, and then again in 1977 with her one-person exhibition at the Detroit Institute of Arts, Works in Progress, much of what was titled Burial Pieces, was previously laid out on the floor of Gallery 7. She has come full circle since that time in this exhibition at Wasserman Projects.

Michele Oka Doner, Book of Psalm, All Images courtesy P.D.Rearick, Wasserman Projects

Always inspired by nature, Michele Oka Doner composes a collection of flattened plant fronds on a grid with variety in the mono-colored objects, giving it the title Book of Psalm. Traditionally, this is a biblical reference in both Christian and Jewish worship as in the Book of Psalm, comprised of religious verse, many ascribed to King David. With a title like that, the subject matter reaches out to many people and relies on their experience for its explanation.

In this exhibition at Wasserman Projects, forty years later, it’s as if this artist has a genre all her own, work fueled by a lifelong study of the natural world. Mathematicians have long established a code for human forms, from plants to rock formations. Best described by Carl G. Jung and explained by Joseph Campbell, Michele Oka Doner exploits the collective unconscious of these forms, shapes and material in her art work.

Alison Wong, Director of Exhibitions at Wasserman Projects says in a statement, “Michele Oka Doner’s illustrious multi-decade practice has been guided by a passion for the natural world, and a fascination with the history held within the remnants of living things, such as twigs, leaves, seeds, shells, pods and stones. In her diverse installations, public works, sculptures, photographs, and drawings, these organic fragments are integrated, replicated and reimagined in new contexts that speak to the ephemeral yet enduring nature of life.”

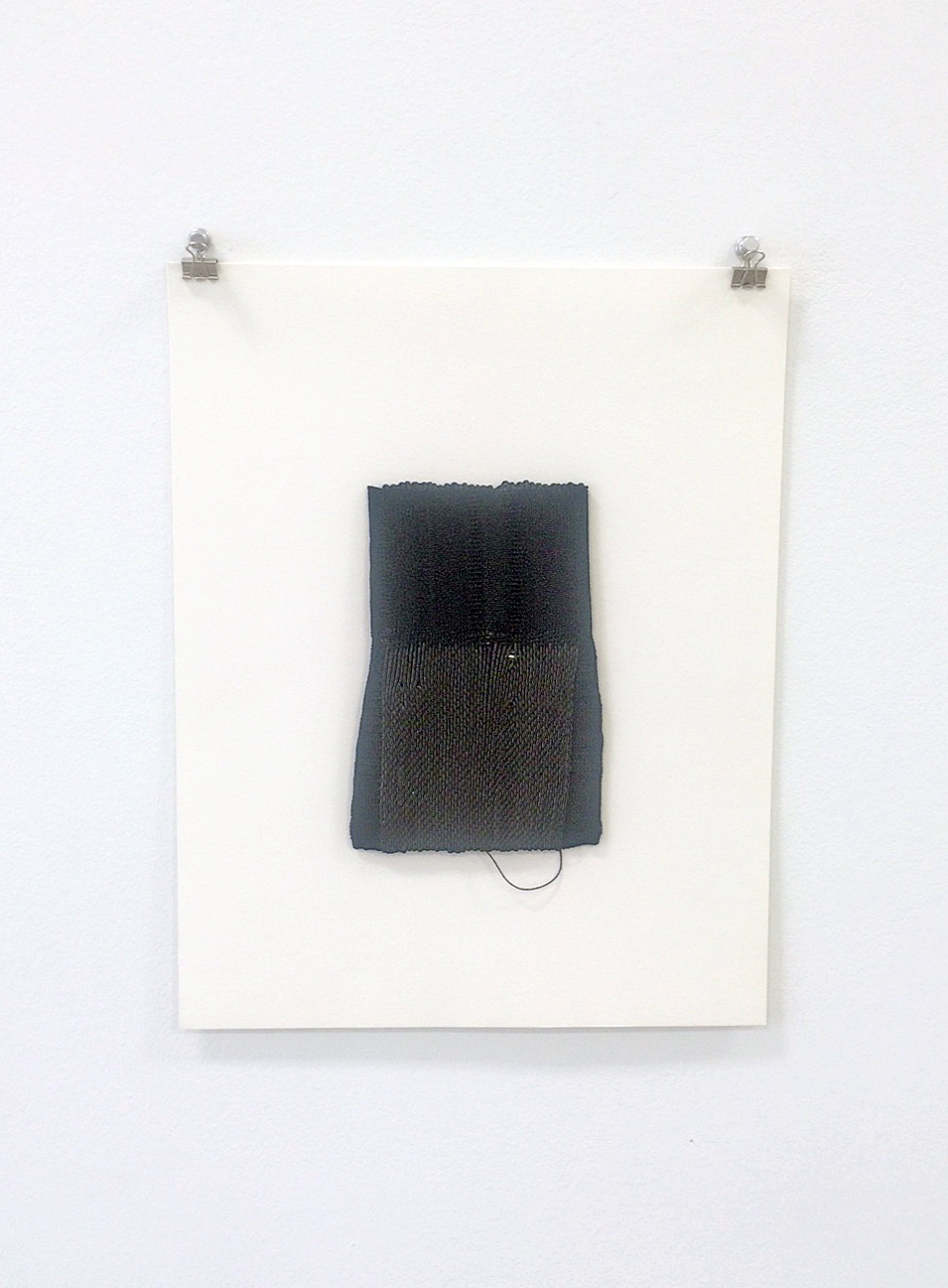

Michele Oka Doner, Inlay Study in plaster.

These shell images and assorted shapes set in a plaster inlay are especially interesting in that the object is modest in size and an abstract composition of spiral shapes. The spiral meaning or symbolism can represent the consciousness of nature beginning from its center and expanding outward. So in keeping with the broad theme of the natural world, Michele Oka Doner works with some of the oldest geometric shapes dating back to the Neolithic period, the product of people over thousands of years, as illustrated in the famous ancient spirals at Newgrange in Ireland. Often the spiral is a feminine symbol, representing not only women, but lifecycles, fertility and childbirth. She places the viewer above and looking down at these various shapes that are cloaked in a gold patina that elevates the meaning.

Michele Oka Doner, Installation of table, objects, and materials.

As part of the exhibition, there is a long table that extends out into the gallery space, which contains a collection of objects, books, various material and sculptures. As the table meets the wall there are two human figures, a child made of porcelain and a standing figure made of terra cotta clay without a head and a spiral-textured surface. These are typical of Michele Oka Doner’s work with the human figure, and in this setting provide a contrast to her dried plant-based work.

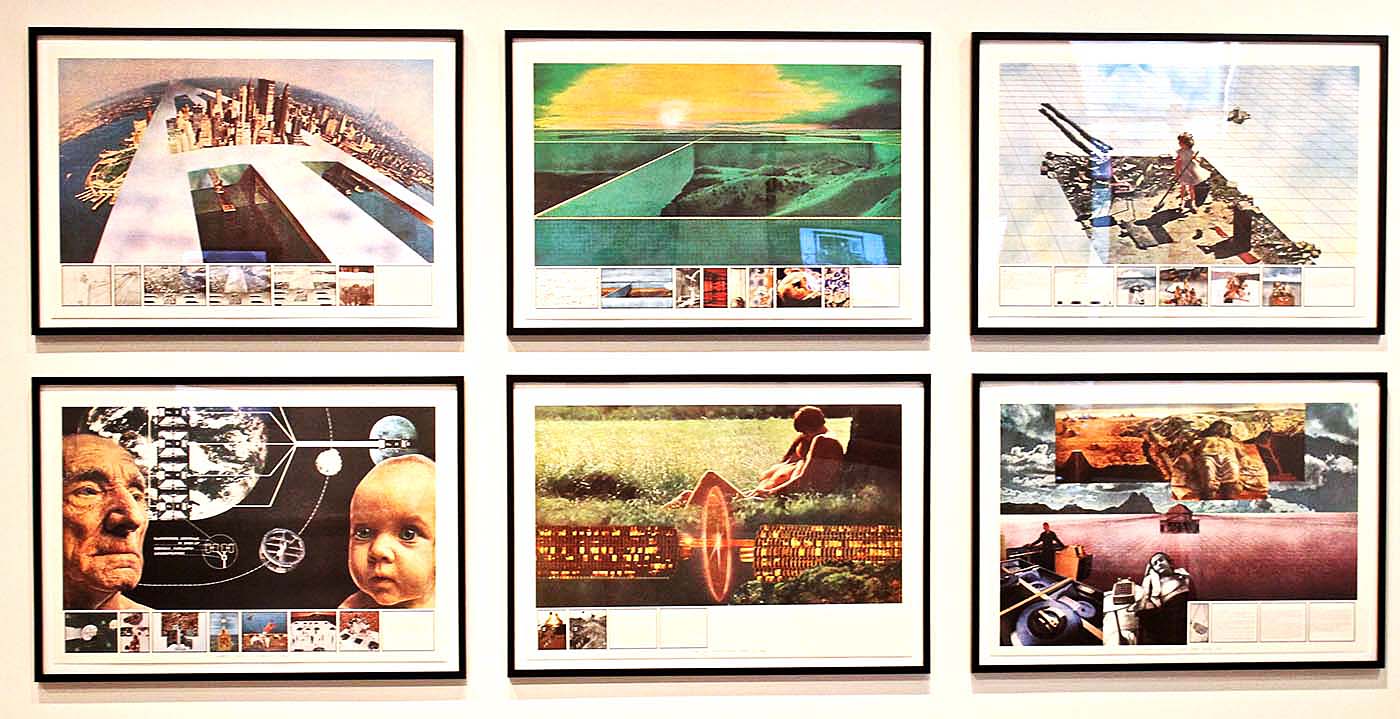

Michele Oka Doner, Glyphs

It has been a mark of her work throughout the years to place these glyph objects on the floor where their light color and textures contrast with the dark concrete floor. Her art becomes the process of making, finding and arranging, these small objects to create questions in the mind of the viewer. It feels like a universal language capable of reaching all people. They are hieroglyphic in nature and vary in size, material and spacing, as if you are looking back in time to a Mayan writing system.

Michele Oka Doner, Whip

Michele Oka Doner was born and raised in Miami Beach, but for thirty years she has lived and worked out of her studio in Soho, New York. She says in an interview with CBS News, in Miami, “I really could speak about what I knew and saw which was an accelerated notion of things growing, sprouting, ripening, decaying, the tides coming, bringing me things when I walked the beach in the morning, taking them away. It was full of wonders and richness. By really learning my own trade, it really was coming out of dipping back into myself instead of reaching out in the world and grasping that I learned daily, a step at a time, to manifest an idea, and that’s as much as we can hope to do in this world.”

Michele Oka Doner received a Bachelor of Science and Design from the University of Michigan (1966), a M.F.A. (1968), was Alumna-in-Residence (1990), received the Distinguished Alumna Award from the School of Art (1994) and was a Penny Stamps Distinguished Speaker (2008). She was awarded the honorary degree, Doctor of Arts (2016).

Her work is in collections worldwide, notably the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Whitney Museum of American Art, and The Cooper-Hewitt, New York; La Musée Des Artes Décoratifs, The Louvre, Paris; The Wolfsoniana, Musei de Genova; The Art Institute of Chicago; The Virginia Museum; The St. Louis Museum; The Dallas Museum of Art; The University of Michigan Museum of Art; The Yale Art Gallery; Princeton University Art Museum; and the Perez Art Museum Miami.

Also on display in the rear gallery is the new work by Detroit based artist/designer Jack Craig.

For the past decade, Oka Doner has been represented by Marlborough Gallery, New York City.

Wasserman Projects, Michele Oka Doner is on exhibit through May 5, 2018.