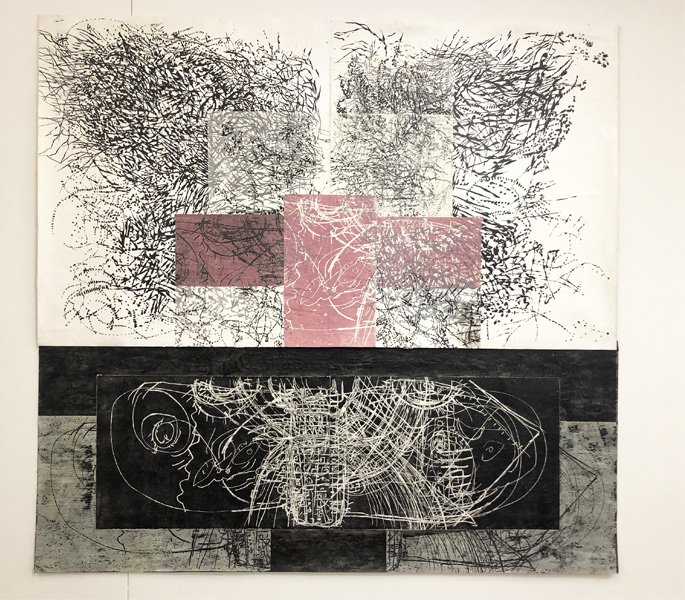

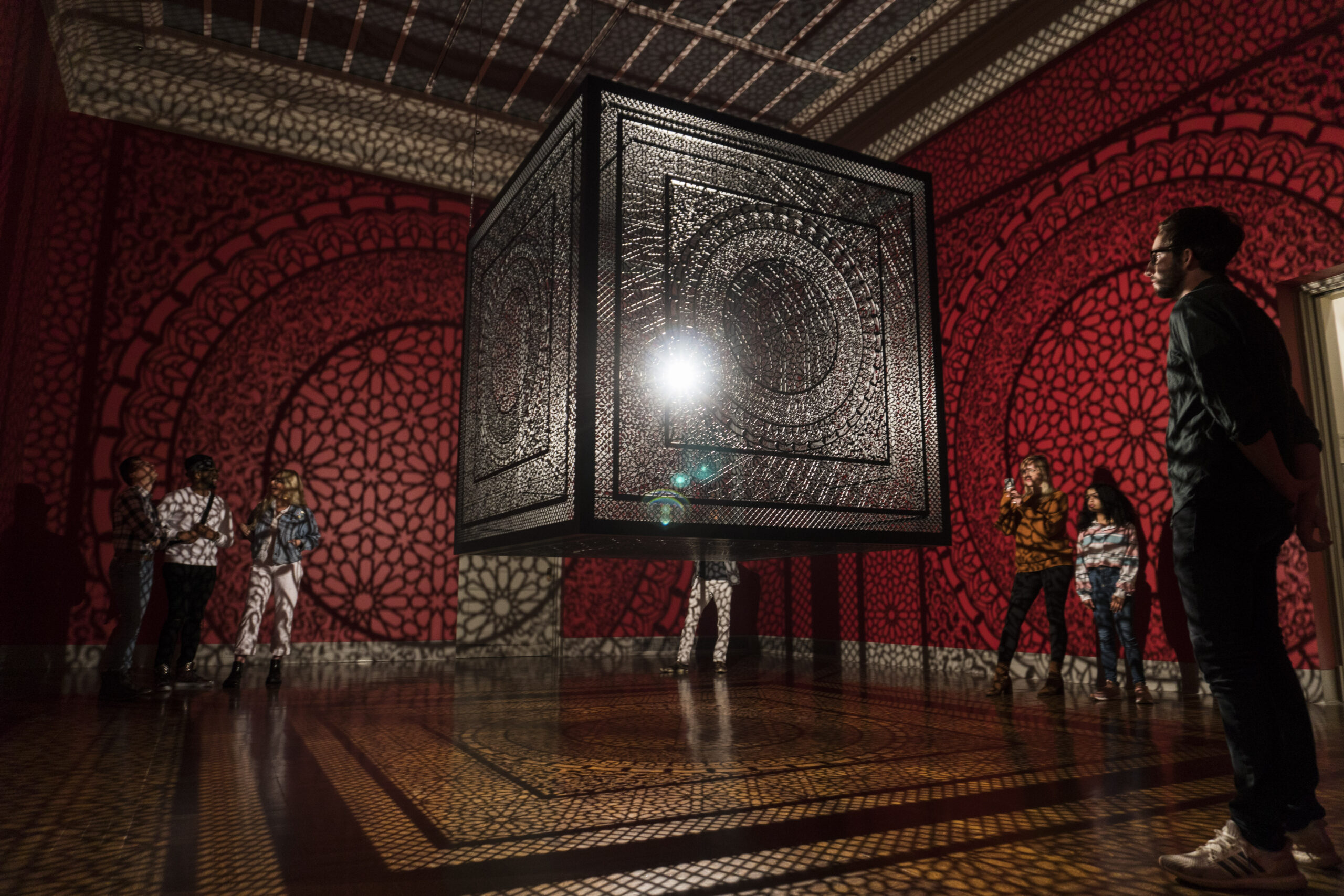

Seeds of Resistance installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2021. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography

Within the Arctic Svalbard Archipelago on the Norwegian island of Spitsbergen is a structure known colloquially as the “Doomsday Vault.” Here, buried deep within a mountain and preserved in sub-zero temperatures are thousands of boxes from all over the world containing roughly a million airtight seed packets. The vault exists to preserve Earth’s biodiversity, acting as a safety net mitigating the environmental effects of any potential natural or human-made ecological disaster. It’s also a sort of United Nations; here you’ll find boxes of seeds deposited by both the United States and North Korea (and they’re quite literally on the same shelf, no less). The Doomsday Vault is just one of many seed vaults and libraries catalogued in Dornith Doherty’s photographic series Archiving Eden: The Vaults, a body of work which documents our best efforts at ecological preservation. At Michigan State University’s Broad Art Museum, her work currently joins that of many other artists who collectively speak to the need for humanity to actively preserve Earth’s biodiversity.

Seeds of Resistance compellingly equates the preservation of seeds with the preservation of genetic information, cultural heritage, and cultural knowledge. The show brings together a diverse body of work by international artists and educators who collectively assert the importance of biodiversity, and reflect on the human imprint on the environment, for better or for ill. The show also celebrates the legacy of MSU’s own Dr. William Beal (1833-1924), the founder of the school’s W.J. Beal Botanical Garden, and whose Seed Viability Experiment remains the longest running scientific experiment in modern history.

Several prominent works on view emphasize the presence of healthy, living soil as integral to any vibrant ecosystem. A large multimedia ensemble by Claire Pentecost invites us to consider the value of healthy soil by drawing a parallel between soil and currency. Here, she stacks blocks of soil sculpted to resemble gold ingots; these are accompanied by twenty-six paintings arranged into a sort of triptych. They collectively represent a hypothetical currency which Pentecost calls the soil-erg, a counterpart to the petro-dollar. Using actual soil to render these images, each painting suggests a different type of imagined bank-note; some commemorate historic figures famous for their contributions to our understanding of agriculture, and others celebrate the non-human creatures that are an integral part of the soil-food web. The earthworm and the bumblebee are championed along with Charles Darwin and Henry David Thoreau.

Seeds of Resistance installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2021. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography

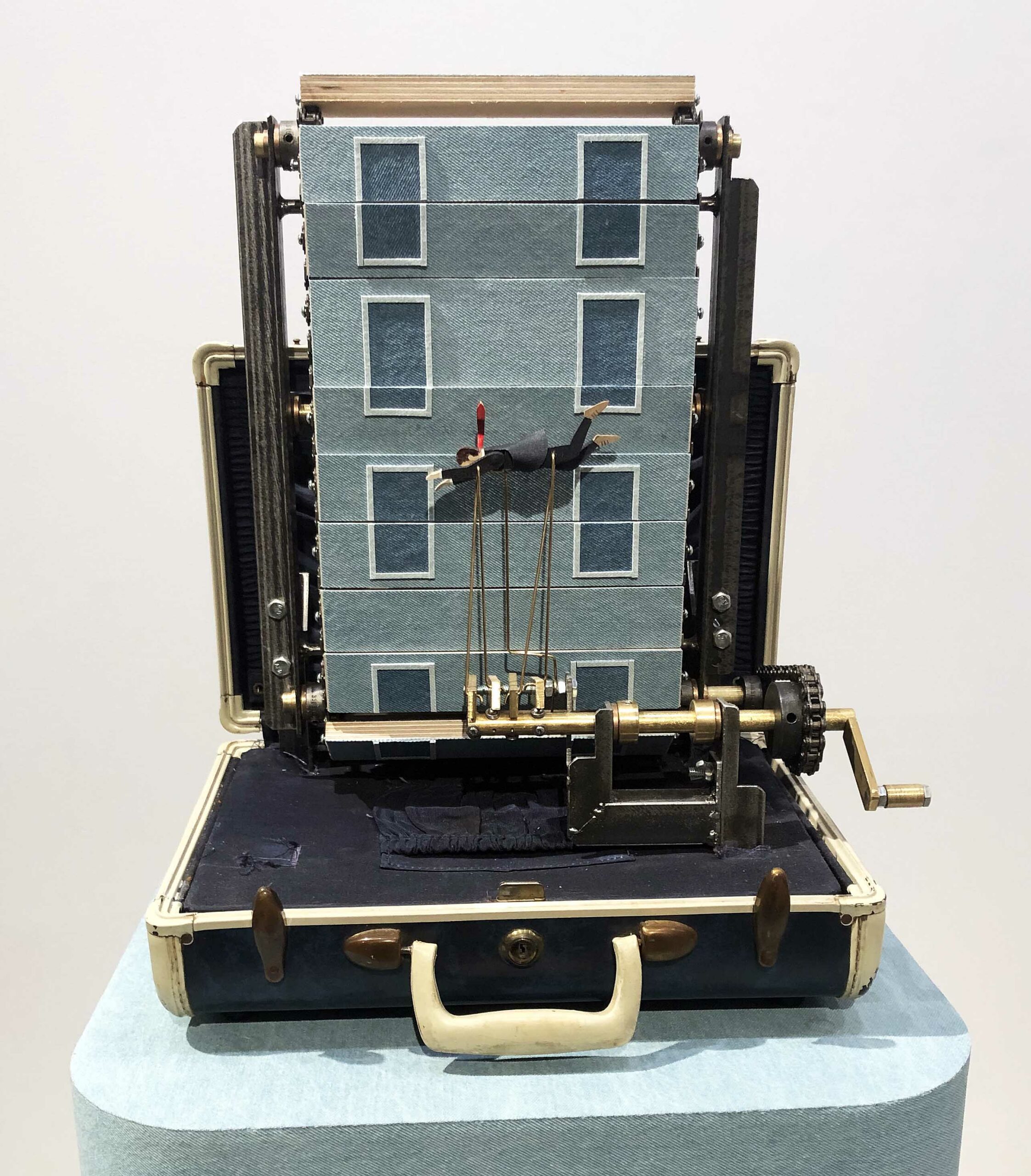

The works of Antonio Moreno and Dylan Miner also thoughtfully underscore the content of their art with the material they work with. For his collective project Live the Free Fields, Moreno invited over fifty participants to fashion over 1,000 mushrooms out of clay (itself a type of soil), which here seem to be sprouting from the floor of the gallery space and together suggest the Earth’s many extant varieties of fungi. Conversely, Dylan Miner speaks to the destruction of healthy ecosystems with a triptych showing a stretch of the Kalamazoo River, the sight of a massive oil spill in 2010. To render the map-like painting, Miner applied bitumen, a type of crude oil, to give the painting its sludgy, oily appearance.

Seeds of Resistance installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2021. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography

Seeds of Resistance installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2021. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography

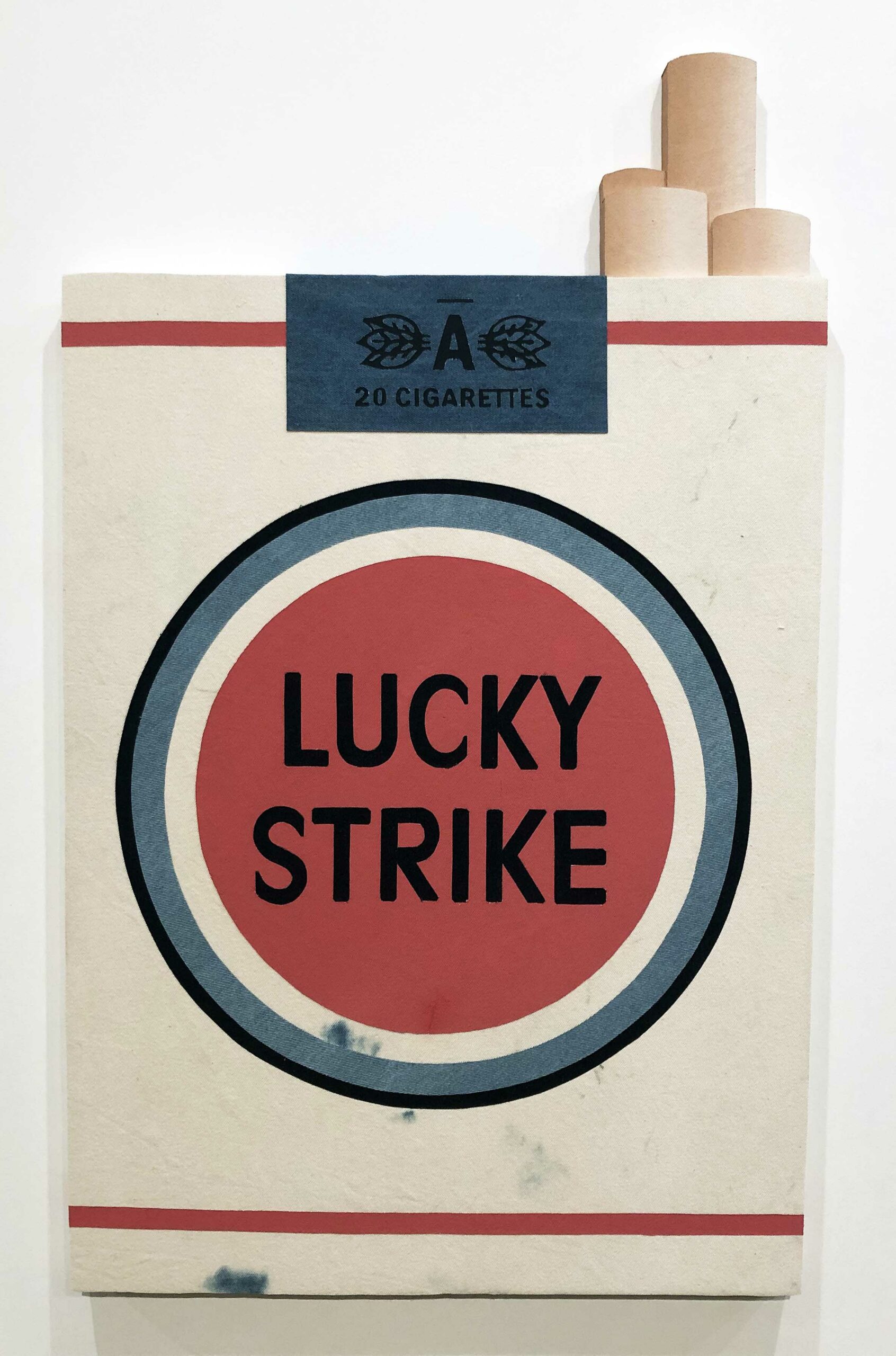

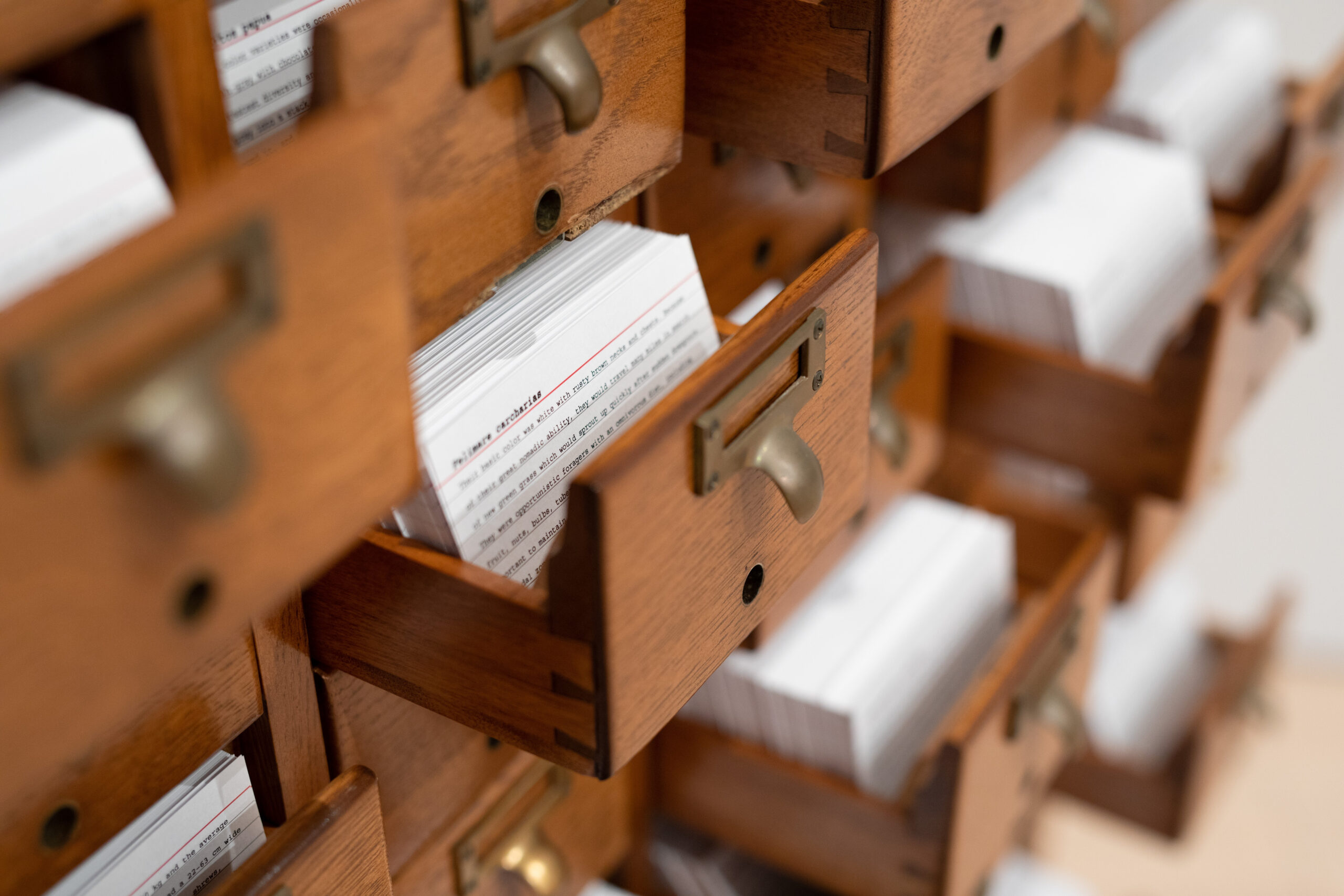

In an adjacent gallery space we find an ensemble of large photographic prints from Dornith Doherty’s Archiving Eden series. Some of these unpeopled images come across as haunting and surreal. Perhaps this is what we might expect, after all, of images documenting a place nicknamed “The Doomsday Vault” (though the place is more properly called the Svalbard Global Seed Vault). Her series documents seed vaults and libraries all over the world though, and some of these libraries are actually very much alive, such as the apple tree collection at Cornell University in New York, which is an orchard preserving over 300 species of apple. Fittingly, in this space her work is complemented with an actual library catalog, itself a conceptual work by Johannes Heldén and Håkan Jonson. With the help of artificial intelligence, the artists filled the drawers of an old-style library catalog with 30,000 index cards, each describing some imaginary future species of creature made extinct by humans. Inside this exhibition’s program/pamphlet, you’ll find several sample copies of these entries on 3×5 index cards (mine included an entry for “Megaptera citri,” described as a social, urban, nocturnal creature made extinct by humans in 2514 AD).

Seeds of Resistance installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2021. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography

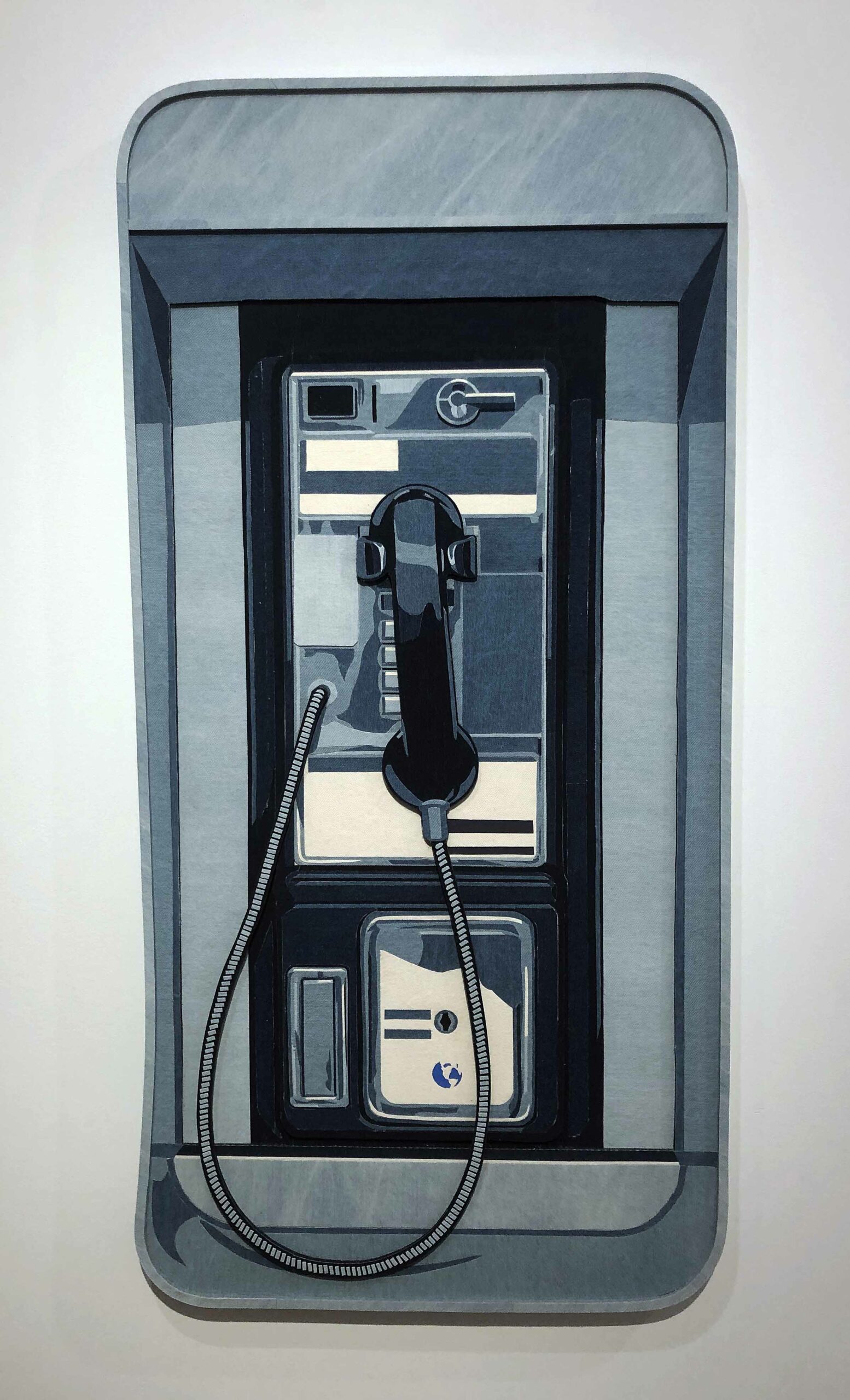

Seeds of Resistance installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2021. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography

Seeds of Resistance installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2021. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography

Supplementing the art in this gallery space are several tables which display artifacts and ephemera that belonged to Dr. William Beal. Here we learn about Beal’s Seed Viability Experiment; launched in 1879, the experiment is still going on today, and it assesses the duration of the seed’s ability to remain dormant and still be able to sprout. The content here is historic and informational rather than artistic, but Beal’s importance to agricultural botany and his significance to MSU aptly makes him a central part of this exhibition.

With Seeds of Resistance, the Broad continues its fine tradition of programming that connects the visual arts with the sciences and other disciplines, and this show in particular makes excellent use of the University’s strengths as an agricultural school. Furthermore, the topic of preserving Earth’s biodiversity is certainly relevant. In 2015, after all, as the direct result of civil war, Syria became the first country that found it necessary to withdraw the seeds it had deposited into the Spitsbergen Norway Seed Vault. It very likely won’t be the last.

Seeds of Resistance is on view at the MSU Broad through July 18.